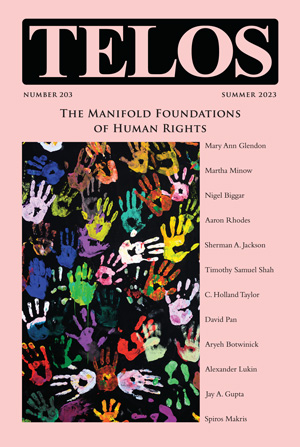

In today’s episode of the Telos Press Podcast, David Pan talks with Sherman A. Jackson about his article “Islam and the Promotion of Human Rights,” from Telos 203 (Summer 2023). An excerpt of the article appears here. If your university has an online subscription to Telos, you can read the full article at the Telos Online website. For non-subscribers, learn how your university can begin a subscription to Telos at our library recommendation page. Print copies of Telos 203 are available for purchase in our online store.

Note: The podcast below was recorded on September 8, 2023.

Islam and the Promotion of Human Rights

Sherman A. Jackson

In his insightful book Human Rights as Politics and Idolatry, Michael Ignatieff observes that “[t]he challenge of Islam has been there from the beginning.”[1] Ignatieff is not alone among Western observers. And in this context, I would like to begin by stating up front that I am neither an opponent of human rights per se nor among those tradition-bound Muslims—though that I am—who abstain from either endorsing the construct or rejecting it outright, presumably as an exercise of sorts in “passive resistance.” Similarly, I do not believe, as another scholar characterizes the position of revealed religion, that “human rights are a secular usurpation of the rights of God.”[2] In fact, as I will show, for well over half a millennium, Muslims have theorized on what could only be considered a concept of human rights, while simultaneously recognizing the “rights of God.” Nor do I believe, contrary to popular perception, that the purportedly “secular” roots of human rights necessarily place them outside the reach of Islam, unless, of course, one assumes, as I do not, that the dominant understanding of “secular” in the West is the only meaning the term can legitimately carry. These are among the reasons why, for me, the idea of summarily rejecting human rights seems so unnecessary if not misguided.

In his insightful book Human Rights as Politics and Idolatry, Michael Ignatieff observes that “[t]he challenge of Islam has been there from the beginning.”[1] Ignatieff is not alone among Western observers. And in this context, I would like to begin by stating up front that I am neither an opponent of human rights per se nor among those tradition-bound Muslims—though that I am—who abstain from either endorsing the construct or rejecting it outright, presumably as an exercise of sorts in “passive resistance.” Similarly, I do not believe, as another scholar characterizes the position of revealed religion, that “human rights are a secular usurpation of the rights of God.”[2] In fact, as I will show, for well over half a millennium, Muslims have theorized on what could only be considered a concept of human rights, while simultaneously recognizing the “rights of God.” Nor do I believe, contrary to popular perception, that the purportedly “secular” roots of human rights necessarily place them outside the reach of Islam, unless, of course, one assumes, as I do not, that the dominant understanding of “secular” in the West is the only meaning the term can legitimately carry. These are among the reasons why, for me, the idea of summarily rejecting human rights seems so unnecessary if not misguided.

Beyond all of this, modern developments in technology alone empower governments, corporations, and even private citizens to invade and dislocate our lives in ways that degrade and humiliate us to the point of denying us even the minimum solace and peace of mind that a dignified existence would seem to require. This is not to mention the unprecedented power that modern states wield, by which they can threaten our physical lives, limbs, and freedom. In such light, it seems critical, now perhaps more than ever, that we arm ourselves with tools and commitments that enable us to protect our basic humanity. And in this context, few things would seem to be more important than “human rights.” Yet precisely for this reason, how and to what end we define, ground, and promote human rights becomes equally important. Herein lies the underlying point of my opening caveat.

Much of what I shall have to say here will signal a certain diffidence if not hostility toward what I read as the general thrust of the focus of our discussion, the U.S. State Department’s Report of the Commission on Unalienable Rights. This has more to do, however, with the Report‘s framing of and approach to human rights than it does with any misgivings about the concept itself. My concern begins with a simple recognition of the global disparity between “the West” and “the rest,” not simply in terms of martial power but also in terms of cultural and intellectual authority. Faced with the reality of having to speak from the minus side of this equation, even the proudest and most principled Muslims often find it useful if not necessary to speak in the voice of the dominant civilization, especially when trying to speak to that civilization or to a world that has been thoroughly saturated by its vision. This is what we find in the most common approaches to human rights among Muslims, which begins with the Western definition and philosophical underpinnings and tries to show how Islam can reconcile itself with these. My fear, however, is that this can habituate Muslims to overlooking aspects of their own civilization, simply because the dominant civilization is not calibrated to recognize these. At the same time, it can habituate the dominant civilization to thinking that its approach to human rights is the only approach, or shall we say the only relevant approach. Given the nagging suspicion that Islam is really only lukewarm regarding human rights, this can prompt the West to approach Muslims as less than reliable partners who need to be “escorted” out of their “false consciousness” and “incentivized” to “get with the human rights program.” And this can end up—and this is my biggest fear—alienating Muslims even further from human rights than they already allegedly, and in some instances actually, are. None of this can be good for the cause of human rights if the aim is to gain the broadest possible support for human rights across the globe, rather than leaving them to be seen and reacted to as the hegemonic tool and property of a single geopolitical interest. These are the primary concerns that animate the thoughts that I will share with you here.

It was not always clear to me from the commission’s Report whether its aim was to garner domestic or international buy-in for human rights. If the former, I suppose it makes sense to stress the ideological and “spiritual” relationship between the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the American rights tradition. This would certainly go a long way toward ingratiating Americans with human rights, including the latter’s purported role as an instrument of American foreign policy. After all, if “human rights” is really just an extension or iteration of America’s domestic commitment to “fundamental” or “inalienable” rights, Americans can embrace the Universal Declaration as essentially theirs, leaving the authenticity of their uniquely American identity intact and unchallenged. If, however, the aim of the Report was to solicit global support for human rights, including its standing and legitimacy in the Muslim world, the alignment of human rights with America’s domestic and international profile may prove counterproductive. The Report makes explicit reference to “the role of human rights in a foreign policy that serves American interests [and] reflects American ideals.”[3] While this “could” simply refer to America’s commitment to remaining mindful of human rights while pursuing its fundamental interests, the optics—or shall I say the “audio”—here are “infelicitous.” As one Muslim law professor based in the United States put it, speaking about the attitude of Western governments toward human rights in the Muslim world:

They advocate it, they praise it, but their deeds belie their words. They lend unconditional support to regimes that consistently violate human rights, so long as these regimes continue to protect Western economic and geopolitical interests.[4]

Or take the bitterly cynical testimony of Ṭāriq al-Zumar, a key organizer of the fundamentalist coalition convicted of assassinating Egyptian president Anwar Sadat in 1981. Al-Zumar spent decades in prison, including years after his sentence had actually expired and he was “re-arrested” and “re-convicted” “on paper.”[5] To his knowledge, however, the global discourse on human rights never took any interest in the torture, dehumanization, and denial of basic rights that he and thousands like him suffered in prison, especially when compared to the plight of secular “dissidents” whose ideological profile appealed to the West. Thus, he wrote back in 2008: “The biggest joke of the entire twenty-first century is ‘human rights,’ especially the version presided over by those butchers and hangmen led by Bush, Brown, Sarkozy, and Merkel.”[6]

The commission’s Report acknowledges that “the ambitious human rights project of the last century is in crisis” (5) and that “enthusiasm for promoting human rights has waned” (49). Yet an overall air of cautious optimism seems to prevail throughout. This struck me as insufficiently aware of and/or sensitive to the deep and ongoing suspicions and resentments that many Muslims around the world nurse toward the notion of human rights, especially as an instrument of American foreign policy. At one point, I was given to ask myself how much of this guarded optimism was grounded in the presumed luxury of being able to ignore the voices of those who do not come to the table as full and equal partners. Even if the suspicions and resentments nursed by Muslims around the world are presumed to be based in false or misguided perceptions, if the point is to ingratiate peoples across the world with human rights, then we must acknowledge the fact that perception matters.

Let me be clear. I have no interest in aiding or abetting any anti-Americanism. Nor do I see any categorical advantage, assuming the persistence of a mono-polar world, in America’s taking a back seat to China, Russia, or any other contender on the global stage today. Yet among the burdens of leadership, at least to my mind, is to recognize that just as it is in the nature of power to enhance if not compel compliance, it is also in its nature to breed resistance. Indeed, William Faulkner argued in his famous exchange with the equally redoubtable James Baldwin that part of the reason the American South tarried so long in granting Blackamericans full citizenship was that Black enfranchisement was being dictated by the triumphant North. From this perspective, if the goal is to move the world, especially the Muslim world, to a fuller embrace of human rights on the level of conscience and actual belief, it may be a mistake to align the construct so singularly with a global superpower whose practical relationship with human rights many see as questionable. The Report presents the Muslim world’s signing onto the Universal Declaration as an entirely voluntary gesture. As the Report put it, “It was testimony to the universal validity of the principles in the Declaration that no UN member was willing to oppose them openly” (5). Once again, however, I found myself taken aback by what struck me as a mildly cynical exercise in intellectual expediency. Everyone knows the state of the world back in 1948, including the gross imbalance of power among nations. Yet the Report seems to invite us to double-down on the fallacy of taking simple acquiescence for actual agreement, a distinction supremely recognized, incidentally, in the American legal concept of “unconscionability,” where the power differential is recognized as a factor that may induce weaker parties into entering into agreements with which they do not really agree.

Continue reading this article at the Telos Online website. If your library does not yet subscribe to Telos, visit our library recommendation page to let them know how.

* This essay is the edited transcript of a lecture by the same title delivered via Zoom for a conference to discuss the U.S. State Department’s Report of the Commission on Unalienable Rights at Notre Dame on November 15, 2021. I am thankful to Paolo Carozza for the invitation. I have made a few cosmetic alterations to make my essay read better in print.

1. Michael Ignatieff, Human Rights as Politics and Idolatry (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 2001), p. 58. Ignatieff ignores, incidentally, the position of Eastern Orthodox Christians, which contributes to the sense that in having any issues with human rights, Islam is a sui generis outlier. On Eastern Orthodox views, see, e.g., Adamantia Pollis, “Eastern Orthodoxy and Human Rights,” Human Rights Quarterly 15, no. 2 (1993): 339–56, where she insists that Eastern Orthodoxy is simply incompatible with human rights.

2. See Boaventura de Sousa Santos, “If God Were a Human Rights Activist: Human Rights and the Challenge of Political Theologies,” Law, Social Justice & Global Development (An Electronic Law Journal) 1 (2009): 18.

3. Commission on Unalienable Rights, Report of the Commission on Unalienable Rights, August 26, 2020 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of State, 2020), p. 6. Subsequent references to the Report will be cited parenthetically within the text.

4. Azizah al-Hibri, “Islam, Law and Custom: Redefining Muslim Women’s Rights,” American University Journal of International Law and Policy 1, no. 4 (1997): 12.

5. In her study of political violence in Egypt, Salwā al-‘Awwa notes that in 1989, “tough-on-extremism” Interior Minister Zakī Badr innovated the practice of serially arresting incarcerated members of Islamic movements on paper in order to extend their sentences indefinitely. See her al-Jamā’ah al-islāmīyah al-musallaḥah fī miṣr, 1974–2004 (Cairo: Maktabat al-Shuūq al-Dawlīyah, 2006), pp. 121–22.

6. See Ṭāriq al-Zumar, Murāja’āt lā tarāju’āt (Cairo: Dār Miṣr al-Maḥrūsah, 2008), p. 9.