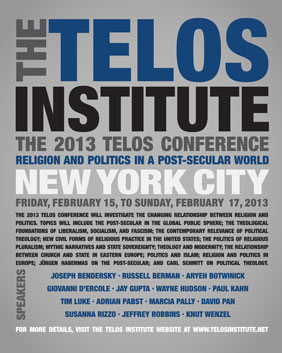

The following paper was presented at the Seventh Annual Telos Conference, held on February 15–17, 2013, in New York City.

Province of Québec’s territory is vast, and much of it has been left in what could be considered a “natural” state. Today’s paper will focus on one particular region called Abitibi-Témiscamingue, located on the west side of the province, but north of Montreal (which is why we usually refer to it as a northern area).

Province of Québec’s territory is vast, and much of it has been left in what could be considered a “natural” state. Today’s paper will focus on one particular region called Abitibi-Témiscamingue, located on the west side of the province, but north of Montreal (which is why we usually refer to it as a northern area).

Abitibi-Témiscamingue has been occupied for more than 8000 years, with the latest occupants being the Algonquins (the Abitibi and the Témiscamingue being the two main groups of Natives living there when Europeans arrived). While their presence has been known since the first French merchants came in the 1700s to trade fur, it is only around 1837–38 that Montreal’s Bishop decided to “take care” of these poor souls and sent missionaries to convert them. In 1863, the Oblate missionaries founded a permanent mission and from there, travelled the entire territory.

Their targets were nomads, travelling in small groups from their summer campground to their winter quarters. They were hunters and gatherers, who never considered the land they live on to be their own. Rather, they saw themselves as keepers and protectors of the land. In all things, they were very conscious of the ones that would come after them.

The arrival of European religious communities was also motivated by a more pragmatic ideal: an economical one. While Algonquins and white travelers had been trading fur for more than a century, both participating in a much larger economical system that included most of North America’s native tribes, a new kind of economy was being developed, that was designed to meet new needs: one of them was the need for wood. With its incredibly vast territory and wilderness, Abitibi-Témiscamingue was an Eldorado of raw material. Starting around 1870, the forest industry of the region was soon the most important one, drawing to its vast territory hundreds of lumberjacks from all over Canada and northern United States. In 1900, more than two thousand lumberjacks were working in Abitibi-Témiscamingue forests, mainly to cut down pinewood. Along with them came farmers, blacksmiths, cooks, artists, and more. To put it simply: everything we, as Westerners, associate with a civilized world. This massive income of settlers was, without a doubt, a great shock to a much older native social organization.

Interrupted by the First World War, the colonization resumed with the development of the transcontinental railway. As the train progressed from east to west, so did the settlers. This time, they were more organized and built permanent structures.

The third wave of settlers came in the aftermath of the Great Depression of 1929. In an attempt to save the Catholic French Canadians from being assimilated by the Protestant English Canadian, the French Canadian elite (mostly a religious one) put together colonization initiatives that resulted in the creation of parishes in Abitibi-Témiscamingue, where mining and agriculture were now also being heavily practiced. The unemployed were sent to these lands only to find themselves in a rude environment, where farming was harsh and resources were somewhat scarce.

As a result of these changes, the Algonquin people tried to adapt to a new lifestyle. Schools were built by missionaries, native people worked as lumberjacks, forest wardens, translators, miners, and so forth. Today, and for few decades now, a movement of native spiritual revival has been undertaken in order to reclaim a territory as well as an identity, both having been dismissed in the name of Progress.

This is the “official” version of the Conquest of Abitibi-Témiscamingue by the Modern World. In this “happy ever after” tale of collaboration, no one gets hurt, no one feels betrayed, and the “Savages” are grateful to the civilized settlers for the knowledge and the wealth they brought with them. Of course, as in any history of conquest, the truth is a much darker one. We will not, in this paper, examine the damage that was done, physically, emotionally and spiritually to the First occupants of the land. We will rather examine this confrontation as a tale of conquest of the Wild. To illustrate how the two universes collided, we will be using Pierre Yergeau’s novels. Pierre Yergeau is an award-winning French Canadian, Abitibi-Témiscamingue-born author and translator. He has published thirteen books, including short stories, essays, and novels. Among these books, four have been focusing on a single family, the Hanse family. The Hanses are members of a travelling circus, travelling along the construction of the railway. First encountered in Yergeau’s first novel, L’écrivain pulic (The Public Writer) in 1999, the Hanse family is composed of nine members.

When he began this great family saga, Pierre Yergeau admitted that he had wanted to write about the creation of a new world. By following the progression of the railway through the wilderness, the circus and its members were penetrating unknown territories, bringing civilization to a bare and disorganize world. In the Forest, a mysterious place that generates what Rudolf Otto would characterize as numinous experiences, these settlers, themselves outcasts in their own world (Yergeau describes the circus as “miserable”), act as a link between a “US” and a “THEM” that can only be seen as a mythical contact, the Forest being the frontier that marks the end of one world and the beginning of the other.

In his Treaty of the History of Religion, Mircea Eliade is eloquent about the function played by vegetation in any religious system. The desecration of the Forest, visual and physical, operated by the railway, can be seen here as an epic tale of Conquest started and won by Québec’s Catholic and political elite. The numinous quality of the forest is emphasized in Pierre Yergeau’s L’écrivain public by an exaggeration of its potential dangers expressed by the adults. Tony, the grandmother of the Hanse children and cook for the entire camp, reminds them regularly of what could happen to them:

(1) “Don’t you go get lost in the woods looking for God knows what! Don’t walk on thawing lakes, or shoot rocks at the flying birds!”

(2) “Don’t climb too high in the trees, of fume weasel dens! Don’t you go and think of yourselves as immortals!”

For these children, the World, the Modern World, of course, is filled with ugliness and filth. They “lived in a dark camp that smelled like sweat,” among the “intoxicating odor of fallen manliness, with a slight sadness caused by the repeated departure (of the lumberjacks) at dawn.”

The brothers, Georges and Jeremy, would stay inside the camp as long as they could, until the feeling of despair became unbearable. Then, they would make a run for it, push the camp door and escape into the woods. Before running outside, they would yell: “Beware! Two filthy children will now operate the delicate passage from the nomad camp to the troubling world of the boreal forest!”

They would then yell and run into the forest, to the dark spruces on the side of the river Nottaway. They were greeted by sleepy groundhogs, stupid yet graceful magpies, and the smell of organic matter: earth, dead animals, dead wood. As Pierre Yergeau puts it: “The Earth’s stomach was breathing again” and Jeremy could feel its pulse beneath his feet.

The opposition of Nature and Culture, as Pierre Yergeau so eloquently describes it, can only be won by one “group.” In creation tales all around the world, civilization has had to battle giants and monsters in order to create the world as it is known. However, this notion of Nature existing outside of ourselves, and therefore being an “enemy” of some sort, is far from universal and has been a trademark of the Western world for the last 2000 years. Examples of this attitude, one that thrives to control and dominate the “Wild” world are numerous, maybe the most famous of them involving God and Adam in Genesis 1:26:

Then God said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. And let them have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.”

This idea of Nature as a source of wealth, as a chaotic ensemble created by God’s will to be tamed, hunted, controlled, caught, supervised and even spoiled is in clear contradiction with the Native ideology. As has been mentioned earlier, the Native people have never viewed themselves as the owner of the Forest and its content. Instead, they saw Man as a part of a greater system, an organic world in which everything and everyone is intertwined.

The Conquest of Abitibi-Témiscamingue is clearly not only a question of economics. Of course, without the fur business of the 18th and 19th centuries, the Europeans might have overlooked this enormous territory as an empty land, completely blind to what the Natives saw as a world of potentials. However, once the land had been “discovered,” it had to be “used” to its full value, which is a commercial value, of course.

In this paper, we do not wish to identify Pierre Yergeau as being for, or against human development. Neither do we intend to judge what happened in Abitibi-Témiscamingue over a century ago. What we have been interested in, and what we wish to keep on exploring, is this notion that commercial and economical development are not as secular as one might think. If we were to task a family of farmers from Rouyn-Noranda, the capital of the region, or a miner going down every day in search for gold (well, maybe robots are doing that now, but we could surely find a human or two!), if they feel like they are contributing to the mythological domination of wilderness, our guess is that they would say ‘no’. However, their presence on that land is a direct consequence of an ideology that had an understanding of the land based on, and nourished by, a religious discourse.

Whether Pierre Yergeau has a distinct opinion on that matter is irrelevant here. What is interesting to us is the way he articulates the interactions between the two worlds, and how the children are the only ones who can travel back and forth without destroying either universe. Because of their innocence or purity, they can come into contact with the sacredness of the Forest, with its danger and its power. With them, the reader comes into contact with a land that is so fabulous, it could even “create its own melody.” Maybe it is time we reflect how we, as “Modern adults” educated in this Man-versus-Wild frame of mind, think of Nature and start thinking of ourselves as a part of Nature.

Notes

* All translations from French to English by Geneviève Pigeon.