By Arthur Bradley · Wednesday, April 1, 2020 Arthur Bradley’s “Terrors of Theory: Critical Theory of Terror from Kojève to Žižek” appears in Telos 190 (Spring 2020): Economy and Ecology: Reconceiving the Human Relationship to Nature. Read the full article at the Telos Online website, or purchase a print copy of the issue in our online store. Individual subscriptions to Telos are available in both print and online formats.

This essay seeks to offer a new genealogy of contemporary critical theory of terror from Alexandre Kojève to Slavoj Žižek. It is clear that critical theory’s response to the volatile post-9/11 geopolitical landscape takes many forms, but one of its most controversial tasks has been a reclamation of the fatal signifier “terror” itself for the radical Left. According to thinkers such as Žižek and Alain Badiou, we must redeem the emancipatory core of the Jacobin Terror from its “Thermodorean” betrayal by two centuries of political and economic liberalism. Yet my claim is that this critical attempt to recuperate terrorism can only be understood in the context of a much longer debate about the meaning of “terror” within twentieth-century European philosophy, which stretches back to Kojève’s lectures on Hegel in the 1930s. This essay tracks the evolution of critical theory of terror from Kojève’s political ontology of terror in his (famously or notoriously) idiosyncratic interpretation of the Hegelian master–slave dialectic to its contemporary conclusion in Žižek’s embrace of Jacobin terror. If Kojève’s lectures effectively introduced Hegel into twentieth-century European philosophy, I will argue that they were also the platform for a wave of neo-Hegelian reflections on the historical, political, and philosophical stakes of terror including, most importantly, Emmanuel Lévinas’s Time and the Other (1947) and Maurice Blanchot’s “Literature and the Right to Death” (1949). In conclusion, I contend that Žižek’s neo-Hegelian defense of the Jacobin leader Robespierre in recent works like In Defense of Lost Causes (2008) might, for better or worse, be read as the latest manifestation of this Kojèvean terrorist legacy. This essay seeks to offer a new genealogy of contemporary critical theory of terror from Alexandre Kojève to Slavoj Žižek. It is clear that critical theory’s response to the volatile post-9/11 geopolitical landscape takes many forms, but one of its most controversial tasks has been a reclamation of the fatal signifier “terror” itself for the radical Left. According to thinkers such as Žižek and Alain Badiou, we must redeem the emancipatory core of the Jacobin Terror from its “Thermodorean” betrayal by two centuries of political and economic liberalism. Yet my claim is that this critical attempt to recuperate terrorism can only be understood in the context of a much longer debate about the meaning of “terror” within twentieth-century European philosophy, which stretches back to Kojève’s lectures on Hegel in the 1930s. This essay tracks the evolution of critical theory of terror from Kojève’s political ontology of terror in his (famously or notoriously) idiosyncratic interpretation of the Hegelian master–slave dialectic to its contemporary conclusion in Žižek’s embrace of Jacobin terror. If Kojève’s lectures effectively introduced Hegel into twentieth-century European philosophy, I will argue that they were also the platform for a wave of neo-Hegelian reflections on the historical, political, and philosophical stakes of terror including, most importantly, Emmanuel Lévinas’s Time and the Other (1947) and Maurice Blanchot’s “Literature and the Right to Death” (1949). In conclusion, I contend that Žižek’s neo-Hegelian defense of the Jacobin leader Robespierre in recent works like In Defense of Lost Causes (2008) might, for better or worse, be read as the latest manifestation of this Kojèvean terrorist legacy.

Continue reading →

By Sean Winkler · Tuesday, March 24, 2020 Sean Winkler’s “Practice and Ideology in Boris Hessen’s ‘The Social and Economic Roots of Newton’s Principia’” appears in Telos 190 (Spring 2020): Economy and Ecology: Reconceiving the Human Relationship to Nature. Read the full article at the Telos Online website, or purchase a print copy of the issue in our online store. Individual subscriptions to Telos are available in both print and online formats.

In this paper, I examine the meaning of and relationship between “practice” and “ideology” in Boris Hessen’s “The Social and Economic Roots of Newton’s Principia.” I propose that for Hessen, practice can be defined as the transformation of things-in-themselves into things-for-us, as well as the transformation of things-in-themselves into things-for-themselves. Ideology, for Hessen, refers to the specific difference between practice and theory, when the practical roots of theory are concealed. In section 1, I explain the Hessen theses and identify means and relations of production as the two kinds of practice presented in the Newton paper. In section 2, I trace the history of the composition and reception of the Hessen theses, showing that any attempt to understand practice and ideology in Hessen’s work requires incorporating his not only Marxist but Deborinite background. In section 3, I explain conceptions of practice and ideology from previous Marxist thinkers and how Hessen, as a Deborinite, may have integrated aspects of these conceptions into his own view. In section 4, I show that Nikolai Bukharin’s “Theory and Practice from the Standpoint of Dialectical Materialism” provides the proper complement for understanding the remaining elements of Hessen’s account. In this paper, I examine the meaning of and relationship between “practice” and “ideology” in Boris Hessen’s “The Social and Economic Roots of Newton’s Principia.” I propose that for Hessen, practice can be defined as the transformation of things-in-themselves into things-for-us, as well as the transformation of things-in-themselves into things-for-themselves. Ideology, for Hessen, refers to the specific difference between practice and theory, when the practical roots of theory are concealed. In section 1, I explain the Hessen theses and identify means and relations of production as the two kinds of practice presented in the Newton paper. In section 2, I trace the history of the composition and reception of the Hessen theses, showing that any attempt to understand practice and ideology in Hessen’s work requires incorporating his not only Marxist but Deborinite background. In section 3, I explain conceptions of practice and ideology from previous Marxist thinkers and how Hessen, as a Deborinite, may have integrated aspects of these conceptions into his own view. In section 4, I show that Nikolai Bukharin’s “Theory and Practice from the Standpoint of Dialectical Materialism” provides the proper complement for understanding the remaining elements of Hessen’s account.

Continue reading →

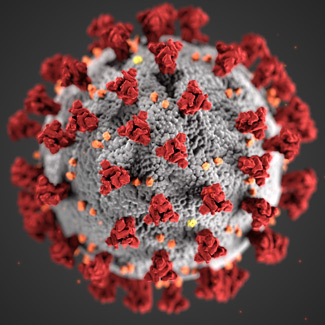

By Saladdin Ahmed · Wednesday, March 18, 2020  There are three reasons to believe that COVID-19 is a communist agent. First, it is universalist; it does not recognize or respect national borders. Second, it is atheist; it has forced cancellations of pilgrimages, along with thousands of other religious rituals. Third, it has been threatening the capitalist economic order across the globe. There are three reasons to believe that COVID-19 is a communist agent. First, it is universalist; it does not recognize or respect national borders. Second, it is atheist; it has forced cancellations of pilgrimages, along with thousands of other religious rituals. Third, it has been threatening the capitalist economic order across the globe.

Perhaps it is inappropriate to joke about COVID-19. However, the pandemic’s increasing traumatic effects across the world are precisely the reason we should also joke about it. Those of us who have lived through calamities realize that sarcasm, far from being disrespectful to human suffering and loss, can be nobler than any serious expression that will inevitably undermine the actual experience. Those of us who have lived through something along the lines of the following examples know the indispensability of sarcasm: living defiantly in the face of the terror devised by a totalitarian regime; being a political prisoner under a fascist regime; taking the first physical steps to leave every place and everyone one has ever known; or, crossing bloody borders in a mythic-like quest in search of a place where one can continue to exist, even if merely as an ontological mistake. Humor is almost a natural coping mechanism when everydayness becomes a struggle for survival. One can easily observe that despite the apparent contradiction, there is more laughter among political prisoners who are facing death than among the affluent in luxurious social settings that are prepared specially to prevent boredom and dread.

Continue reading →

By David Pan · Monday, March 16, 2020 Telos 190 (Spring 2020): Economy and Ecology: Reconceiving the Human Relationship to Nature is now available for purchase in our store. Individual subscriptions to Telos are also available in both print and online formats.

Our human relationship to nature defines our economic life. As Marx articulated in the 1844 manuscripts, labor involves an engagement with nature in order to fulfill human ends, the working up of nature as an “inorganic body.” Consequently, the world of work and that of the environment are really two aspects of our relationship to nature, and the shift in academic interest from economy to ecology as the burning issue of the day does not represent any real change in perspective. On a fundamental level, economy is ecology and vice versa. Thus, the issue of climate change is primarily one about the energy structure of our economy. If that structure before the Industrial Revolution boiled down to the way in which we were cutting down our forests, today the issue is how fossil fuels are leading to climate change. The other global natural disaster of our day, the coronavirus, has arisen as a consequence, first, of our treatment of wild animals as food and, second, of economic globalization, whose movements have established the pathways for the rapid spread of viruses. Our human relationship to nature defines our economic life. As Marx articulated in the 1844 manuscripts, labor involves an engagement with nature in order to fulfill human ends, the working up of nature as an “inorganic body.” Consequently, the world of work and that of the environment are really two aspects of our relationship to nature, and the shift in academic interest from economy to ecology as the burning issue of the day does not represent any real change in perspective. On a fundamental level, economy is ecology and vice versa. Thus, the issue of climate change is primarily one about the energy structure of our economy. If that structure before the Industrial Revolution boiled down to the way in which we were cutting down our forests, today the issue is how fossil fuels are leading to climate change. The other global natural disaster of our day, the coronavirus, has arisen as a consequence, first, of our treatment of wild animals as food and, second, of economic globalization, whose movements have established the pathways for the rapid spread of viruses.

Continue reading →

By Telos Press · Friday, February 21, 2020 Writing in the new issue of Philosophy in Review, Adam Sliwowski reviews Carl Schmitt’s The Tyranny of Values and Other Texts, translated by Samuel Garrett Zeitlin, edited by Russell A. Berman and Samuel Garrett Zeitlin, with a preface by David Pan. Order your copy in our online store, and save 20% on the list price by using the coupon code BOOKS20 during the checkout process.

An excerpt:

The works of Carl Schmitt—a German jurist and political theorist infamous for his involvement with National Socialism—continue to have wide international appeal, influencing scholars in a number of fields from political science and jurisprudence to political-theology and existential philosophy. Nevertheless, much of his prolific oeuvre, written over the span of almost 70 years, remains untranslated into English. With The Tyranny of Values and Other Texts, Samuel Garrett Zeitlin takes a step in filling this gap with an edited collection of finely translated and helpfully annotated texts that appear in English for the first time. This collection of occasional pieces, spanning from the Weimar era to the Cold War, shows Schmitt responding to a diverse array of socio-political exigencies and world-historical developments, while also shedding light on many of the central themes of Schmitt’s work, such as the distinction between legality and legitimacy, land and sea, the nomos of the earth, and the figure of the partisan. The works of Carl Schmitt—a German jurist and political theorist infamous for his involvement with National Socialism—continue to have wide international appeal, influencing scholars in a number of fields from political science and jurisprudence to political-theology and existential philosophy. Nevertheless, much of his prolific oeuvre, written over the span of almost 70 years, remains untranslated into English. With The Tyranny of Values and Other Texts, Samuel Garrett Zeitlin takes a step in filling this gap with an edited collection of finely translated and helpfully annotated texts that appear in English for the first time. This collection of occasional pieces, spanning from the Weimar era to the Cold War, shows Schmitt responding to a diverse array of socio-political exigencies and world-historical developments, while also shedding light on many of the central themes of Schmitt’s work, such as the distinction between legality and legitimacy, land and sea, the nomos of the earth, and the figure of the partisan.

Continue reading →

By Andrey N. Medushevsky · Thursday, January 2, 2020 Andrey N. Medushevsky’s “Law and Revolution: The Impact of Soviet Legitimacy on Post-Soviet Constitutional Transformation” appears in Telos 189 (Winter 2019), a special issue on constitutional theory. Read the full article at the Telos Online website, or purchase a print copy of the issue in our online store. Individual subscriptions to Telos are available in both print and online formats.

The systematic investigation of the Russian revolutionary tradition in comparative, historical, and functional perspective provides the opportunity to understand its impact on the creation of the modern world and the contemporary social and political system. This article discusses the meaning, formation, and evolution of the Soviet project—the concept and practice of social and legal reorganization in Russia inspired by Marxist philosophical ideas and fulfilled during the period from the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 until the collapse of the Soviet regime in 1991. Employing a cognitive theoretical approach in historical studies, the author examines the role of Communist myth in the formation of the Soviet state, the ideological and legal grounds of one-party dictatorship, the nature of nominal constitutionalism, and the role of institutional continuity in the formation of the current political system. He shows the place of the permanent grounds (ideology, nominal constitutionalism, and dictatorial impetus) as well as the place of changing parameters of the project (Soviet, federative, and class-oriented regulation) regarding their formal and informal influence on the political regime’s legitimacy and the cumulative impact on the system’s transformation and failure. In this context, the author discusses the evolution of the legitimating formula of the political regime from Tsarist times to the collapse of the Soviet regime, as represented in ideological programmatic, nominal Soviet constitutionalism (1918, 1924, 1936, and 1977 Soviet constitutions) and changing practices of the social mobilization. That makes possible the general evaluation of the revolutionary heritage and its influence on the current post-Soviet ideological priorities, political system, legal transformation, and prospects for its modernization. The systematic investigation of the Russian revolutionary tradition in comparative, historical, and functional perspective provides the opportunity to understand its impact on the creation of the modern world and the contemporary social and political system. This article discusses the meaning, formation, and evolution of the Soviet project—the concept and practice of social and legal reorganization in Russia inspired by Marxist philosophical ideas and fulfilled during the period from the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 until the collapse of the Soviet regime in 1991. Employing a cognitive theoretical approach in historical studies, the author examines the role of Communist myth in the formation of the Soviet state, the ideological and legal grounds of one-party dictatorship, the nature of nominal constitutionalism, and the role of institutional continuity in the formation of the current political system. He shows the place of the permanent grounds (ideology, nominal constitutionalism, and dictatorial impetus) as well as the place of changing parameters of the project (Soviet, federative, and class-oriented regulation) regarding their formal and informal influence on the political regime’s legitimacy and the cumulative impact on the system’s transformation and failure. In this context, the author discusses the evolution of the legitimating formula of the political regime from Tsarist times to the collapse of the Soviet regime, as represented in ideological programmatic, nominal Soviet constitutionalism (1918, 1924, 1936, and 1977 Soviet constitutions) and changing practices of the social mobilization. That makes possible the general evaluation of the revolutionary heritage and its influence on the current post-Soviet ideological priorities, political system, legal transformation, and prospects for its modernization.

Continue reading →

|

|

This essay seeks to offer a new genealogy of contemporary critical theory of terror from Alexandre Kojève to Slavoj Žižek. It is clear that critical theory’s response to the volatile post-9/11 geopolitical landscape takes many forms, but one of its most controversial tasks has been a reclamation of the fatal signifier “terror” itself for the radical Left. According to thinkers such as Žižek and Alain Badiou, we must redeem the emancipatory core of the Jacobin Terror from its “Thermodorean” betrayal by two centuries of political and economic liberalism. Yet my claim is that this critical attempt to recuperate terrorism can only be understood in the context of a much longer debate about the meaning of “terror” within twentieth-century European philosophy, which stretches back to Kojève’s lectures on Hegel in the 1930s. This essay tracks the evolution of critical theory of terror from Kojève’s political ontology of terror in his (famously or notoriously) idiosyncratic interpretation of the Hegelian master–slave dialectic to its contemporary conclusion in Žižek’s embrace of Jacobin terror. If Kojève’s lectures effectively introduced Hegel into twentieth-century European philosophy, I will argue that they were also the platform for a wave of neo-Hegelian reflections on the historical, political, and philosophical stakes of terror including, most importantly, Emmanuel Lévinas’s Time and the Other (1947) and Maurice Blanchot’s “Literature and the Right to Death” (1949). In conclusion, I contend that Žižek’s neo-Hegelian defense of the Jacobin leader Robespierre in recent works like In Defense of Lost Causes (2008) might, for better or worse, be read as the latest manifestation of this Kojèvean terrorist legacy.

This essay seeks to offer a new genealogy of contemporary critical theory of terror from Alexandre Kojève to Slavoj Žižek. It is clear that critical theory’s response to the volatile post-9/11 geopolitical landscape takes many forms, but one of its most controversial tasks has been a reclamation of the fatal signifier “terror” itself for the radical Left. According to thinkers such as Žižek and Alain Badiou, we must redeem the emancipatory core of the Jacobin Terror from its “Thermodorean” betrayal by two centuries of political and economic liberalism. Yet my claim is that this critical attempt to recuperate terrorism can only be understood in the context of a much longer debate about the meaning of “terror” within twentieth-century European philosophy, which stretches back to Kojève’s lectures on Hegel in the 1930s. This essay tracks the evolution of critical theory of terror from Kojève’s political ontology of terror in his (famously or notoriously) idiosyncratic interpretation of the Hegelian master–slave dialectic to its contemporary conclusion in Žižek’s embrace of Jacobin terror. If Kojève’s lectures effectively introduced Hegel into twentieth-century European philosophy, I will argue that they were also the platform for a wave of neo-Hegelian reflections on the historical, political, and philosophical stakes of terror including, most importantly, Emmanuel Lévinas’s Time and the Other (1947) and Maurice Blanchot’s “Literature and the Right to Death” (1949). In conclusion, I contend that Žižek’s neo-Hegelian defense of the Jacobin leader Robespierre in recent works like In Defense of Lost Causes (2008) might, for better or worse, be read as the latest manifestation of this Kojèvean terrorist legacy.  There are three reasons to believe that COVID-19 is a communist agent. First, it is universalist; it does not recognize or respect national borders. Second, it is atheist; it has forced cancellations of pilgrimages, along with thousands of other religious rituals. Third, it has been threatening the capitalist economic order across the globe.

There are three reasons to believe that COVID-19 is a communist agent. First, it is universalist; it does not recognize or respect national borders. Second, it is atheist; it has forced cancellations of pilgrimages, along with thousands of other religious rituals. Third, it has been threatening the capitalist economic order across the globe.