Telos 185 (Winter 2018) is now available for purchase in our store. Individual subscriptions to Telos are also available in both print and online formats.

Recall the 2016 campaign and even more the aftermath of the Trump victory: otherwise reasonable people rushed into heated rhetoric regarding the imminence of dictatorship and the end of democracy as we know it. Comparisons of the America of 2016 and Germany of 1933 proliferated, while denunciations of Republicans as Nazis or Nazi collaborators became common. It would be a worthwhile project for a student or scholar of American culture to cull through those statements and confront their authors with them today: if they were so wrong in 2016, what value is their judgment today, moving forward?

Recall the 2016 campaign and even more the aftermath of the Trump victory: otherwise reasonable people rushed into heated rhetoric regarding the imminence of dictatorship and the end of democracy as we know it. Comparisons of the America of 2016 and Germany of 1933 proliferated, while denunciations of Republicans as Nazis or Nazi collaborators became common. It would be a worthwhile project for a student or scholar of American culture to cull through those statements and confront their authors with them today: if they were so wrong in 2016, what value is their judgment today, moving forward?

For those predictions were simply and utterly wrong. Of course, the Republican in the White House and the Republican-controlled Congress pursued a version of a conservative agenda (although not always with success, as in the case of health care). But the rule of law prevailed, courts could decide against the government, the liberal part of the press has been articulate in its critique of administration policies, and, in a quite normal and proper manner, the midterm elections took place. American institutions have proven much more robust than the hysterics of little faith claimed in 2016. Those prophets of dictatorship owe us an accounting—or actually an apology—for their hyperbole. They significantly trivialized what really happened under the Nazi dictatorship, and they cavalierly slandered that slightly less than half of the American electorate that voted for Trump. Time for some critical self-reflection? This is not at all a suggestion that they must endorse the president, but it is way past time for them to concede that his supporters are not a priori Nazis, no matter how much juvenile fun name-calling affords.

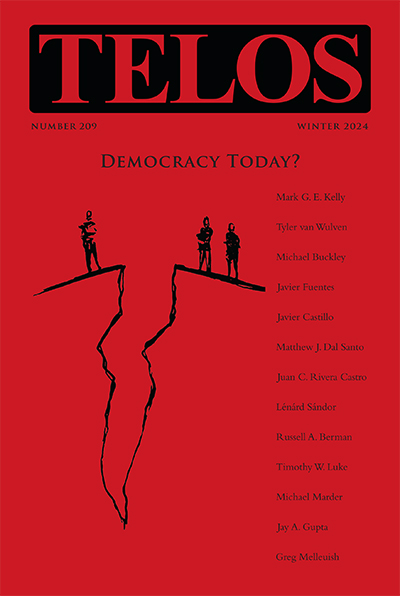

But to claim that American electoral and judicial institutions have operated fairly well does not mean that nothing is changing. On the contrary, there are profound shifts underway in our democratic vistas, even if they do not map neatly onto one party or the other, or even onto one president. The partisan rhetoric circus obscures the fact that we are doing democracy differently, reflecting current social and technological shifts, long-standing vectors in the American experiment as well as in the possibilities of politics altogether, topics of traditional political philosophy. This issue of Telos brings together a set of contributions to shed light on some of these matters.

The Trump administration faced criticism early on from proponents of traditional U.S. foreign policy, but the rhetoric obscured some deeper continuity with his predecessor. Both President Obama and President Trump showed reluctance to become involved in large land wars, like the Iraq War, or extensive bombing campaigns, like the Clinton agenda in the Balkans. On a tectonic level, there is a rethinking underway of America’s place in the world. Initially it might have seemed as if an isolationism from the left, e.g., Obama’s withdrawal from the Middle East and a broader anti-imperialist inflection, had simply given way to an isolationism from the right, Trump’s break with multilateral trade agreements (although the left opposed them too). While there may be something to that hypothesis, the matter is more complex, and the first article in this issue, Tim Luke‘s inquiry into democracy and imperialism, provides important historical depth. Luke traces American space from the “onshore empire,” settling the continent, to the “offshore empire” on the oceans, and then the dominance in the skies. The argument follows Carl Schmitt’s elemental thinking, earth, water, and air, but it points beyond to a fourth arena, outer space: interplanetary travel as the conceptual alternative to “land” wars? In Luke’s words, “rhetoric from the White House about creating a new Space Force, militarizing outer space, and competing to colonize the moon, in order to live there permanently in way stations to colonize Mars and extract lunar resources for use back on earth, is not entirely a joke, although many are laughing.” It is however really not a laughing matter, but potentially the next phase of an American agenda, precisely a rejection of “blood and soil” earth-boundedness (on this point too the fascism accusation does not hold up), while the aspiration for space travel gives an unexpected additional meaning to the critique of “globalism.”

In the meantime, more traditional international affairs continue, and while China has emerged rapidly as the primary competitor and even potential adversary for the United States, our political debate remains dominated by Russia narratives. To be sure, there is much that is unsavory in the manner of Putinist rule, including but not limited to the annexation of Crimea and the disruption in eastern Ukraine. Yet some rapprochement with Russia could have the strategic advantage of pulling Moscow away from Beijing (recall the pact of Nixon in China, but now worked in the opposite direction). Nonetheless, articulating such an agenda is nearly impossible given the predominance of the Russia collusion story, which is so tenacious because it has served to explain the Clinton loss in 2016 and to hammer President Trump: it has much less to do with Russia than with American political competition. Richard Sakwa‘s account of the “The End of the Revolution” combines a deep knowledge of Russia with a theoretical apparatus indebted to Girard and Bakhtin in order to explain the status of the relations between Russia and the West and to suggest how things could be different. The dogmatism of Communism, which defined the Russian side in the Cold War, has disappeared—at least in Russia, where alternative traditions propose supple, flexible, and heterogeneous paradigms of community, including a multipolar world community. Instead dogmatism—in this idiom, “dialectical thinking”—has migrated to the West in, for example, the neo-Hegelian vision of the triumph of neoliberalism in the Fukuyama thesis of “the end of history.” (That liberal triumphalism moreover might be seen as continuing the imperialism of “Manifest Destiny” that plays an important role in Luke’s account.) Historical irony is at work here, as Sakwa explains: “The sort of dialectical politics that characterized the Soviet Union for seventy years has migrated to the West and is now advanced in the service of the axiological expansion of an existing order. By contrast, the dialogical potential of politics is now advanced at the international level by Russia. There are deep Russian roots to political dialogism, which offers the potential to transform not only international affairs but the domestic polity as well. The seat of dialectical thinking has moved from Russia to the West, while in Russia, and large parts of the East in general, the potential for dialogic thinking is being recovered.”

Politics as a profession has become, to a considerable extent, a primarily quantitative project, not only in the pursuit of a democratic majority, a numerical phenomenon, but also in the obligation to perpetual fundraising combined with the transformation of voters from citizens into data points. This quantification of political life stands at odds with traditional sources of legitimacy, which include the mixture of personal integrity and political theology that are at stake in the notion of the oath of office. Politicians swear loyalty, and Mitchell Dean explains why this is not a merely ritualistic ceremony, as well as the scope of its significance: “It is in the political life of the United States that the oath seems to have taken a visible presence. This most dramatically concerns the testimony to special counsels of presidents from Clinton to Trump, with the former being charged with perjury under the articles of his impeachment. One also thinks of James Comey’s appearance as former director of the FBI before the Senate Intelligence Committee on June 8, 2017, and President Donald Trump’s subsequent accusation that Comey lied under oath in that testimony. It seems that picking oath violations can become a kind of political sport. On February 20, 2018, the New York Times sent out an email to its subscribers with the elementary subject line ‘Trump violates his oath.'” Dean goes on to show that the oath as an element of politics is not by any means restricted to American democracy. It is however indicative of a profound expectation of fidelity and trust that may be an ever rarer feature of political life.

Jumping to the “Critical Theory of the Contemporary” section, which concludes this issue of Telos, we offer some additional pointed commentaries on the political matters at hand. Tim Luke (who also contributed the lead article) writes on Bob Woodward’s account of the administration, especially the populist success at calling out the policy failings of both traditional parties: “Despite Woodward’s Watergate-tested ‘deep background’ style of reporting, he contextualizes many of the currents running through the populist turn in the United States in the 2010 national midterm elections, which legitimized the key conservative nationalist themes woven into Donald J. Trump’s unyielding assault on both the Democratic and Republican parties for failing to protect American jobs, to stop illegal immigration, and to win the war against radical Islamic terrorism from 2011 through 2016.”

Daniel Innerarity returns us to the Trump victory in 2016 and offers a cogent explanation for the inability to come to terms with the electoral outcome. Much more compelling than blaming it on Russian spies, it is the cleavage in American society that is at stake, as he points to “the withdrawal of a civilized minority that distances itself from ‘populist’ impulses, not so much because it has a superior idea of democracy as because it does not suffer the threats of a precarious situation like those hardest hit by the crisis or it does not understand the fears of those at the bottom. The ruling elites do not have a good understanding of what is happening within our societies, probably because they find themselves in enclosed environments that make it hard for them to understand other situations. There are no shared experiences or common vision; just private comfort, on the one hand, and invisible suffering, on the other. Those who have turned in the direction of public affairs have not understood how corrosive for democracy persistent inequality and difference of opportunities are proving to be. The multiple upheavals experienced by American society (with its equivalents in other parts of the world), from the Tea Party to Trump or, at the opposite extreme, from the Occupy Wall Street movement to the unexpected success of Bernie Sanders, are the symptoms of a disaffection with a forced ‘modernity’ on the part of Americans, while the elite and its formidable propaganda apparatus repeat over and over again that there is no other possible viewpoint.”

Adrian Pabst looks at American politics from the vantage point of the United Kingdom and argues that liberalism and its seeming antipode, populism, may have more in common with each other than meets the eye, which leads him to propose a third alternative that involves a reformed and socially aware conservatism that values community: “The alternative to ‘Trumpism’ so understood (in either ‘right’ or ‘left’ permutations) is not traditional social democracy, which history has now overtaken. It is rather the ‘conservative socialism’ of Blue Labour in Britain and the new party Refondation in France. In different ways, both combine a more just and socially purposed market with more allowance for attachments to religion, custom, and place than the left has been happy with since the 1960s—as Christopher Lasch and Paul Piccone were among the first to diagnose. Such a politics remains committed to a traditional humanism, whose ontological undergirding religious believers and those with a metaphysical sensibility defend against the secular positivisms of both liberals and anti-liberals. The defense of humanism is the new pivot in politics.”

After the elections, our democratic vistas remain defined as well by deep political-philosophical legacies discussed in a remarkable group of contributions that this issue brings together. Panajotis Kondylis helps us explain the dialectic of relativism and universalism with regard to problems of tolerance: is the universal ever truly tolerant of the particular? The question is crucial for the vicissitudes of multiculturalism as a feature of early twenty-first-century democratic polities. Marco Andreacchio discusses political theology in Vico’s epistemology, and Loralea Michaelis approaches the foundational figure of Critical Theory, Max Horkheimer, with figures of thought borrowed from Rosa Luxemburg, German communist and early critic of Leninist Bolshevism. Johann Rossouw looks at Bernard Stiegler’s theological thought as a critical reflection on modernity, and Walter Rech treats the event in international law. Our issue also includes two reviews: Elena Pilipets reads Huimin Jin’s Active Audience, a discussion of cultural studies; and Sara-Maria Sorentino reviews Simone Browne’s Dark Matters.