If a journal manages to survive for 100 issues, it is reasonable to assume that the editorial board has managed to reach some sort of internal consensus and can finally rest on its laurels. Such is not the case with Telos. . . . After all these years, nothing seems to be settled and [Telos] remains a hopelessly heterogeneous group still trying to come to some agreement concerning many crucial and not-so-crucial issues. . . . This is why this theoretical bellum omnium contra omnes may be interpreted as evidence of lingering internal vitality, an unwillingness to take anything for granted, and a suspicion of all positions even faintly resembling conformism and passivity.

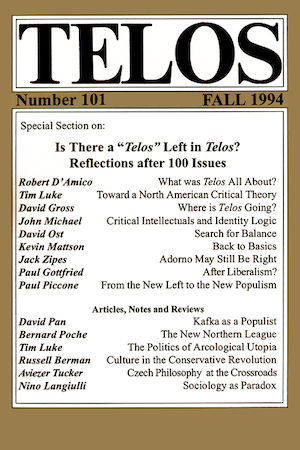

With those words from Telos 101 (Fall 1994), Paul Piccone launched his critique of those who felt Telos had lost its direction and had settled into the role of the cranky old uncle of intellectual journals. Having just celebrated its 200th issue in its 54th year, those words still speak to the current state of the intellectual project he launched back in 1968.

With those words from Telos 101 (Fall 1994), Paul Piccone launched his critique of those who felt Telos had lost its direction and had settled into the role of the cranky old uncle of intellectual journals. Having just celebrated its 200th issue in its 54th year, those words still speak to the current state of the intellectual project he launched back in 1968.

Piccone’s critique of his critics, “From the New Left to the New Populism,” was intended not to lay claim to any settled doctrine for Telos but to demonstrate the journal’s ability to constantly rethink its position among current debates along the entire ideological spectrum. While the bellum omnium contra omnes Piccone refers to in his article specifically refers to Telos‘s own family, I think it is more than fair to say it was applied to any and all who asserted a suspicious and artificial ground for emancipation. Toward this end, Piccone begins by providing his own critique of the Western Marxist tradition out of which Telos arose. This in itself, in its pure compactness, is a tour de force of intellectual history and should be read by all those who seek an origin story, or who simply need to have their revision revised.