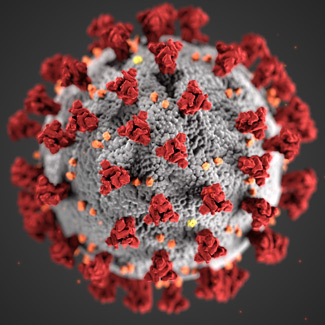

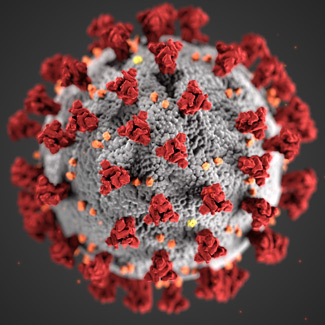

By Saladdin Ahmed · Wednesday, March 18, 2020  There are three reasons to believe that COVID-19 is a communist agent. First, it is universalist; it does not recognize or respect national borders. Second, it is atheist; it has forced cancellations of pilgrimages, along with thousands of other religious rituals. Third, it has been threatening the capitalist economic order across the globe. There are three reasons to believe that COVID-19 is a communist agent. First, it is universalist; it does not recognize or respect national borders. Second, it is atheist; it has forced cancellations of pilgrimages, along with thousands of other religious rituals. Third, it has been threatening the capitalist economic order across the globe.

Perhaps it is inappropriate to joke about COVID-19. However, the pandemic’s increasing traumatic effects across the world are precisely the reason we should also joke about it. Those of us who have lived through calamities realize that sarcasm, far from being disrespectful to human suffering and loss, can be nobler than any serious expression that will inevitably undermine the actual experience. Those of us who have lived through something along the lines of the following examples know the indispensability of sarcasm: living defiantly in the face of the terror devised by a totalitarian regime; being a political prisoner under a fascist regime; taking the first physical steps to leave every place and everyone one has ever known; or, crossing bloody borders in a mythic-like quest in search of a place where one can continue to exist, even if merely as an ontological mistake. Humor is almost a natural coping mechanism when everydayness becomes a struggle for survival. One can easily observe that despite the apparent contradiction, there is more laughter among political prisoners who are facing death than among the affluent in luxurious social settings that are prepared specially to prevent boredom and dread.

Continue reading →

By Andrey N. Medushevsky · Thursday, January 2, 2020 Andrey N. Medushevsky’s “Law and Revolution: The Impact of Soviet Legitimacy on Post-Soviet Constitutional Transformation” appears in Telos 189 (Winter 2019), a special issue on constitutional theory. Read the full article at the Telos Online website, or purchase a print copy of the issue in our online store. Individual subscriptions to Telos are available in both print and online formats.

The systematic investigation of the Russian revolutionary tradition in comparative, historical, and functional perspective provides the opportunity to understand its impact on the creation of the modern world and the contemporary social and political system. This article discusses the meaning, formation, and evolution of the Soviet project—the concept and practice of social and legal reorganization in Russia inspired by Marxist philosophical ideas and fulfilled during the period from the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 until the collapse of the Soviet regime in 1991. Employing a cognitive theoretical approach in historical studies, the author examines the role of Communist myth in the formation of the Soviet state, the ideological and legal grounds of one-party dictatorship, the nature of nominal constitutionalism, and the role of institutional continuity in the formation of the current political system. He shows the place of the permanent grounds (ideology, nominal constitutionalism, and dictatorial impetus) as well as the place of changing parameters of the project (Soviet, federative, and class-oriented regulation) regarding their formal and informal influence on the political regime’s legitimacy and the cumulative impact on the system’s transformation and failure. In this context, the author discusses the evolution of the legitimating formula of the political regime from Tsarist times to the collapse of the Soviet regime, as represented in ideological programmatic, nominal Soviet constitutionalism (1918, 1924, 1936, and 1977 Soviet constitutions) and changing practices of the social mobilization. That makes possible the general evaluation of the revolutionary heritage and its influence on the current post-Soviet ideological priorities, political system, legal transformation, and prospects for its modernization. The systematic investigation of the Russian revolutionary tradition in comparative, historical, and functional perspective provides the opportunity to understand its impact on the creation of the modern world and the contemporary social and political system. This article discusses the meaning, formation, and evolution of the Soviet project—the concept and practice of social and legal reorganization in Russia inspired by Marxist philosophical ideas and fulfilled during the period from the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 until the collapse of the Soviet regime in 1991. Employing a cognitive theoretical approach in historical studies, the author examines the role of Communist myth in the formation of the Soviet state, the ideological and legal grounds of one-party dictatorship, the nature of nominal constitutionalism, and the role of institutional continuity in the formation of the current political system. He shows the place of the permanent grounds (ideology, nominal constitutionalism, and dictatorial impetus) as well as the place of changing parameters of the project (Soviet, federative, and class-oriented regulation) regarding their formal and informal influence on the political regime’s legitimacy and the cumulative impact on the system’s transformation and failure. In this context, the author discusses the evolution of the legitimating formula of the political regime from Tsarist times to the collapse of the Soviet regime, as represented in ideological programmatic, nominal Soviet constitutionalism (1918, 1924, 1936, and 1977 Soviet constitutions) and changing practices of the social mobilization. That makes possible the general evaluation of the revolutionary heritage and its influence on the current post-Soviet ideological priorities, political system, legal transformation, and prospects for its modernization.

Continue reading →

By Vasiliy A. Shchipkov · Thursday, October 5, 2017 The following paper was presented at the conference “After the End of Revolution: Constitutional Order amid the Crisis of Democracy,” co-organized by the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute and the National Research University Higher School of Economics, September 1–2, 2017, Moscow. For additional details about the conference as well as other upcoming events, please visit the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute website.

It is important not only to analyze the legacy of the Russian Revolution of 1917 from the point of view of historical science, but also to bear in mind its impact on the modern information and ideological processes. Discussing the Russian Revolution has become a way to think and talk about today, and different approaches to the discussion correspond to different views on modernity and different political ethics. There are five approaches to the evaluation of the Russian Revolution in the ideological space of today: the classic liberal, the neoliberal, the Western left, the Russian left, and the traditionalist approach.

Continue reading →

By Linas Jokubaitis · Thursday, September 26, 2013 As an occasional feature on TELOSscope, we highlight a past Telos article whose critical insights continue to illuminate our thinking and challenge our assumptions. Today, Linas Jokubaitis looks at Paul Piccone’s “Lukács’s History and Class Consciousness Half a Century Later,” from Telos 4 (Fall 1969).

In 1969, when Paul Piccone wrote “Lukács’s History and Class Consciousness Half a Century Later,” almost fifty years had passed since the publication of Georg Lukács’s magnum opus. Piccone wrote this essay to mark that anniversary, and he argued that this work was an “underground classic.” Moreover, he asserted that this book was essential for any analysis of modern thought. According to Piccone, everyone attempting to understand and overcome the ideological crisis of Marxism would be wise to consult this book. In 1969, when Paul Piccone wrote “Lukács’s History and Class Consciousness Half a Century Later,” almost fifty years had passed since the publication of Georg Lukács’s magnum opus. Piccone wrote this essay to mark that anniversary, and he argued that this work was an “underground classic.” Moreover, he asserted that this book was essential for any analysis of modern thought. According to Piccone, everyone attempting to understand and overcome the ideological crisis of Marxism would be wise to consult this book.

Continue reading →

By Sunil Kumar · Tuesday, July 3, 2012 As an occasional feature on TELOSscope, we highlight a past Telos article whose critical insights continue to illuminate our thinking and challenge our assumptions. Today, Sunil Kumar looks at Theodor W. Adorno’s “The Stars Down to Earth: The Los Angeles Times Astrology Column,” from Telos 19 (Spring 1974).

“The Stars Down to Earth” is the content analysis of an astrology column that Adorno wrote during a return visit to the United States from Germany in 1952–53 and appeared in translation in Telos in 1974. The column under scrutiny called, “Astrological Forecasts,” was written by Carroll Righter and appeared in the Los Angeles Times, described by Adorno as a conservative newspaper, leaning far to the right wing of the Republican Party. He engages in a detailed analysis of the column between November 1952 and February 1953. His method is that of the systematic construction of the imagined readers of the column and a critique of the ideology that the column reinforces, that of accepting the social system as fate. Adorno hypothesizes that columns such as these mold to some extent the reader’s thinking and foster an element of blind acceptance. The impetus of the piece, as in “The Thesis against Occultism” (1947), is to highlight the tendency toward irrationality and authoritarianism in mid-twentieth-century Western culture. In the analysis of the column, this irrationality is reflected by the readers’ acceptance of the column’s absurd claim to be inspired by the stars, and the need to look for guidance and succor in the advice of an expert authority on mundane matters. The stars stand in for the reader of the column as a source of authority, and the belief in astrology represents for him or her a belief in a higher order—one that also appears to present to events a veneer of rationality to its opaque origin. “The Stars Down to Earth” is the content analysis of an astrology column that Adorno wrote during a return visit to the United States from Germany in 1952–53 and appeared in translation in Telos in 1974. The column under scrutiny called, “Astrological Forecasts,” was written by Carroll Righter and appeared in the Los Angeles Times, described by Adorno as a conservative newspaper, leaning far to the right wing of the Republican Party. He engages in a detailed analysis of the column between November 1952 and February 1953. His method is that of the systematic construction of the imagined readers of the column and a critique of the ideology that the column reinforces, that of accepting the social system as fate. Adorno hypothesizes that columns such as these mold to some extent the reader’s thinking and foster an element of blind acceptance. The impetus of the piece, as in “The Thesis against Occultism” (1947), is to highlight the tendency toward irrationality and authoritarianism in mid-twentieth-century Western culture. In the analysis of the column, this irrationality is reflected by the readers’ acceptance of the column’s absurd claim to be inspired by the stars, and the need to look for guidance and succor in the advice of an expert authority on mundane matters. The stars stand in for the reader of the column as a source of authority, and the belief in astrology represents for him or her a belief in a higher order—one that also appears to present to events a veneer of rationality to its opaque origin.

Continue reading →

By Jakob Norberg · Thursday, January 12, 2012 Jakob Norberg’s “Day-to-Day Politics: Carl Schmitt on the Diary” appears in Telos 157 (Winter 2011). Read the full version online at the TELOS Online website, or purchase a print copy of the issue here.

Early on in his career, Carl Schmitt articulated a cultural critique of the diary. He saw the personal journal as a manifestation and reinforcement of the writing subject’s vanity and self-importance in a sterile modern world. The resulting record, moreover, offered up the diarist’s inner life to the gaze of dissecting readers, who tended to convert polemical arguments into psychological symptoms. Yet Schmitt also kept something like a daily journal and was thus forced to struggle against the diary from within the genre itself. His post-1945 notebooks, entitled Glossarium, constitute a cultural battlefield upon which this struggle takes place. By means of strategies such as scathing portraits of famous diarists and displays of sententious concision, Schmitt sought to expel the diary from his own notebooks, or stage a paradoxical day-to-day resistance to the pathologies of the age emblematized in the diary form itself. The study of Schmitt’s non-diary ultimately sheds light on his political understanding of writing. For him, genres are never neutral vehicles of ideas but rather inflect thought in ideologically relevant ways. Early on in his career, Carl Schmitt articulated a cultural critique of the diary. He saw the personal journal as a manifestation and reinforcement of the writing subject’s vanity and self-importance in a sterile modern world. The resulting record, moreover, offered up the diarist’s inner life to the gaze of dissecting readers, who tended to convert polemical arguments into psychological symptoms. Yet Schmitt also kept something like a daily journal and was thus forced to struggle against the diary from within the genre itself. His post-1945 notebooks, entitled Glossarium, constitute a cultural battlefield upon which this struggle takes place. By means of strategies such as scathing portraits of famous diarists and displays of sententious concision, Schmitt sought to expel the diary from his own notebooks, or stage a paradoxical day-to-day resistance to the pathologies of the age emblematized in the diary form itself. The study of Schmitt’s non-diary ultimately sheds light on his political understanding of writing. For him, genres are never neutral vehicles of ideas but rather inflect thought in ideologically relevant ways.

Continue reading →

|

|

There are three reasons to believe that COVID-19 is a communist agent. First, it is universalist; it does not recognize or respect national borders. Second, it is atheist; it has forced cancellations of pilgrimages, along with thousands of other religious rituals. Third, it has been threatening the capitalist economic order across the globe.

There are three reasons to believe that COVID-19 is a communist agent. First, it is universalist; it does not recognize or respect national borders. Second, it is atheist; it has forced cancellations of pilgrimages, along with thousands of other religious rituals. Third, it has been threatening the capitalist economic order across the globe.

In 1969, when Paul Piccone wrote “Lukács’s History and Class Consciousness Half a Century Later,” almost fifty years had passed since the publication of Georg Lukács’s magnum opus. Piccone wrote this essay to mark that anniversary, and he argued that this work was an “underground classic.” Moreover, he asserted that this book was essential for any analysis of modern thought. According to Piccone, everyone attempting to understand and overcome the ideological crisis of Marxism would be wise to consult this book.

In 1969, when Paul Piccone wrote “Lukács’s History and Class Consciousness Half a Century Later,” almost fifty years had passed since the publication of Georg Lukács’s magnum opus. Piccone wrote this essay to mark that anniversary, and he argued that this work was an “underground classic.” Moreover, he asserted that this book was essential for any analysis of modern thought. According to Piccone, everyone attempting to understand and overcome the ideological crisis of Marxism would be wise to consult this book.  “The Stars Down to Earth” is the content analysis of an astrology column that Adorno wrote during a return visit to the United States from Germany in 1952–53 and appeared in translation in Telos in 1974. The column under scrutiny called, “Astrological Forecasts,” was written by Carroll Righter and appeared in the Los Angeles Times, described by Adorno as a conservative newspaper, leaning far to the right wing of the Republican Party. He engages in a detailed analysis of the column between November 1952 and February 1953. His method is that of the systematic construction of the imagined readers of the column and a critique of the ideology that the column reinforces, that of accepting the social system as fate. Adorno hypothesizes that columns such as these mold to some extent the reader’s thinking and foster an element of blind acceptance. The impetus of the piece, as in “The Thesis against Occultism” (1947), is to highlight the tendency toward irrationality and authoritarianism in mid-twentieth-century Western culture. In the analysis of the column, this irrationality is reflected by the readers’ acceptance of the column’s absurd claim to be inspired by the stars, and the need to look for guidance and succor in the advice of an expert authority on mundane matters. The stars stand in for the reader of the column as a source of authority, and the belief in astrology represents for him or her a belief in a higher order—one that also appears to present to events a veneer of rationality to its opaque origin.

“The Stars Down to Earth” is the content analysis of an astrology column that Adorno wrote during a return visit to the United States from Germany in 1952–53 and appeared in translation in Telos in 1974. The column under scrutiny called, “Astrological Forecasts,” was written by Carroll Righter and appeared in the Los Angeles Times, described by Adorno as a conservative newspaper, leaning far to the right wing of the Republican Party. He engages in a detailed analysis of the column between November 1952 and February 1953. His method is that of the systematic construction of the imagined readers of the column and a critique of the ideology that the column reinforces, that of accepting the social system as fate. Adorno hypothesizes that columns such as these mold to some extent the reader’s thinking and foster an element of blind acceptance. The impetus of the piece, as in “The Thesis against Occultism” (1947), is to highlight the tendency toward irrationality and authoritarianism in mid-twentieth-century Western culture. In the analysis of the column, this irrationality is reflected by the readers’ acceptance of the column’s absurd claim to be inspired by the stars, and the need to look for guidance and succor in the advice of an expert authority on mundane matters. The stars stand in for the reader of the column as a source of authority, and the belief in astrology represents for him or her a belief in a higher order—one that also appears to present to events a veneer of rationality to its opaque origin.  Early on in his career, Carl Schmitt articulated a cultural critique of the diary. He saw the personal journal as a manifestation and reinforcement of the writing subject’s vanity and self-importance in a sterile modern world. The resulting record, moreover, offered up the diarist’s inner life to the gaze of dissecting readers, who tended to convert polemical arguments into psychological symptoms. Yet Schmitt also kept something like a daily journal and was thus forced to struggle against the diary from within the genre itself. His post-1945 notebooks, entitled Glossarium, constitute a cultural battlefield upon which this struggle takes place. By means of strategies such as scathing portraits of famous diarists and displays of sententious concision, Schmitt sought to expel the diary from his own notebooks, or stage a paradoxical day-to-day resistance to the pathologies of the age emblematized in the diary form itself. The study of Schmitt’s non-diary ultimately sheds light on his political understanding of writing. For him, genres are never neutral vehicles of ideas but rather inflect thought in ideologically relevant ways.

Early on in his career, Carl Schmitt articulated a cultural critique of the diary. He saw the personal journal as a manifestation and reinforcement of the writing subject’s vanity and self-importance in a sterile modern world. The resulting record, moreover, offered up the diarist’s inner life to the gaze of dissecting readers, who tended to convert polemical arguments into psychological symptoms. Yet Schmitt also kept something like a daily journal and was thus forced to struggle against the diary from within the genre itself. His post-1945 notebooks, entitled Glossarium, constitute a cultural battlefield upon which this struggle takes place. By means of strategies such as scathing portraits of famous diarists and displays of sententious concision, Schmitt sought to expel the diary from his own notebooks, or stage a paradoxical day-to-day resistance to the pathologies of the age emblematized in the diary form itself. The study of Schmitt’s non-diary ultimately sheds light on his political understanding of writing. For him, genres are never neutral vehicles of ideas but rather inflect thought in ideologically relevant ways.