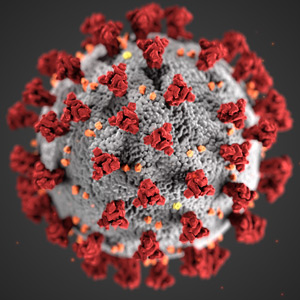

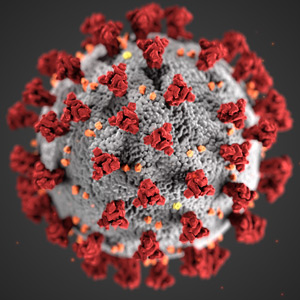

By Russell A. Berman · Tuesday, August 18, 2020 The pandemic crisis has surfaced fundamental tensions between the scope of state power and commitments to democracy and dissent. Facing an emergency, the state must act vigorously, but liberal democracies are premised on understandings of basic rights, maximal freedom, and limited government, desiderata at odds with state power. This opposition has been playing out in different ways in the United States and in Europe, and in Europe nowhere more saliently than in Germany.

A recent controversy in Germany provides insight into the process by which the need to respond to the pandemic acts as a vehicle to enhance state power in a way that threatens basic freedoms. This is the core conflict: the genuine urgency of developing public health measures to contain the pandemic can contribute simultaneously to the augmentation of state power. Questions of the vitality of democracy are at stake, and not only in Germany.

Continue reading →

By Arta Khakpour · Wednesday, July 22, 2020 In 1972, Irving Kristol noted the striking fact that the New Left seemed to lack a coherent economic critique of the status quo, besides occasional Marxist platitudes borrowed from the Old Left:

The identifying marks of the New Left are its refusal to think economically and its contempt for bourgeois society precisely because this is a society that does think economically.

What really ailed American society, and what the New Left could sense but not articulate, Kristol wrote, was a spiritual malady. Despite the efforts of Burkean conservatives, the “accumulated moral capital of traditional religion and traditional moral philosophy” had been steadily depleting since the French Revolution, and with its depletion, so too society’s abilities to cope with the material inequalities, resentments, and indignities made inevitable by the free exchange of goods and services.

Continue reading →

By Russell A. Berman · Thursday, April 9, 2020  Once upon a time, there was an illusion that the state would disappear. It was the fiction Marxists told each other at bedtime, and it was the lie of the Communists, once they had seized state power. For even as they built up their police apparatus and their archipelago of gulags, they kept promising that one day the state would eventually disappear. Once upon a time, there was an illusion that the state would disappear. It was the fiction Marxists told each other at bedtime, and it was the lie of the Communists, once they had seized state power. For even as they built up their police apparatus and their archipelago of gulags, they kept promising that one day the state would eventually disappear.

Of course, in a sense, they were right because Communism ended and so did the Communist states in Russia and Eastern Europe. Yet the death of those regimes is in no way an argument for the death of statehood itself.

The state is the expression of sovereignty, and sovereignty is the ability of national communities to decide their own fates. Such independence is far from obsolete, and certainly not for the countries on the eastern flank of the European Union. After years of Russian occupation, they have regained their state sovereignty. They will continue to insist on it, and rightly so.

Continue reading →

By Saladdin Ahmed · Sunday, June 16, 2019 The ongoing Sudanese revolution has emerged at a time when most of us had already given up any realistic hope for what has become known as the Arab Spring. Yet, if anything, the revolutionaries in Sudan have the best chance yet of simultaneously defeating both nationalist dictatorship and religious fundamentalism. This would be no small feat; it would arguably mark the most significant historical turning point in the struggle for democracy in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) since World War II.

Since the protests began in Tunisia in late 2010, the Arab Spring has repeatedly failed to deliver on its promise of democratic governance. I argue that this is primarily because the protest movements have simply not been revolutionary enough to break free from the dominating orbit of the retroactive forces of nationalist dictatorships and religious fundamentalism. Under these circumstances, the non-violent, mostly liberal movements were quickly neutralized, demonstrating the degree to which the death of the Left has left contemporary societies at the mercy of fascist forces.

Continue reading →

By Mitchell Dean · Friday, February 8, 2019 Mitchell Dean’s “Oath and Office” appears in Telos 185 (Winter 2018). Read the full article at the Telos Online website, or purchase a print copy of the issue in our online store. Individual subscriptions to Telos are available in both print and online formats.

The oath pertains to law, sovereignty, and office. A public servant takes an oath. A witness and a juror at a trial swear an oath. The British monarch swears a coronation oath and the president-elect of the United States an oath of office. While the coronation of the monarch has been regarded as “medieval” and the inauguration of the president as “ceremonial” or “symbolic,” it would be a mistake to view them as empty rituals, particularly the oaths taken. And while the oath invokes God, it would be an error to assume that it is merely an atavism, a retroversion, or a vestige of a more religious past. But what it is and what it does is far from clear, including to those who swear oaths. When President Obama, sworn in by Chief Justice John Roberts, misspoke his oath of office in January 2009, he was advised to retake it the next day, as the White House counsel put it, “out of an abundance of caution.” Ex abundanti cautela might indeed by the principle that scholars should adopt, given the thicket of false trails, unfathomable origins, prejudices, and commonplaces that afflict any attempt to study this practice. The appropriate method to study the oath uses multiple examples and cases, considers them from as many different viewpoints as it can, and remains wary of both our commonsense assumptions about its origins and efficacy and their theoretical correlates. The oath pertains to law, sovereignty, and office. A public servant takes an oath. A witness and a juror at a trial swear an oath. The British monarch swears a coronation oath and the president-elect of the United States an oath of office. While the coronation of the monarch has been regarded as “medieval” and the inauguration of the president as “ceremonial” or “symbolic,” it would be a mistake to view them as empty rituals, particularly the oaths taken. And while the oath invokes God, it would be an error to assume that it is merely an atavism, a retroversion, or a vestige of a more religious past. But what it is and what it does is far from clear, including to those who swear oaths. When President Obama, sworn in by Chief Justice John Roberts, misspoke his oath of office in January 2009, he was advised to retake it the next day, as the White House counsel put it, “out of an abundance of caution.” Ex abundanti cautela might indeed by the principle that scholars should adopt, given the thicket of false trails, unfathomable origins, prejudices, and commonplaces that afflict any attempt to study this practice. The appropriate method to study the oath uses multiple examples and cases, considers them from as many different viewpoints as it can, and remains wary of both our commonsense assumptions about its origins and efficacy and their theoretical correlates.

Continue reading →

By Russell A. Berman · Wednesday, December 12, 2018 Telos 185 (Winter 2018) is now available for purchase in our store. Individual subscriptions to Telos are also available in both print and online formats.

Recall the 2016 campaign and even more the aftermath of the Trump victory: otherwise reasonable people rushed into heated rhetoric regarding the imminence of dictatorship and the end of democracy as we know it. Comparisons of the America of 2016 and Germany of 1933 proliferated, while denunciations of Republicans as Nazis or Nazi collaborators became common. It would be a worthwhile project for a student or scholar of American culture to cull through those statements and confront their authors with them today: if they were so wrong in 2016, what value is their judgment today, moving forward? Recall the 2016 campaign and even more the aftermath of the Trump victory: otherwise reasonable people rushed into heated rhetoric regarding the imminence of dictatorship and the end of democracy as we know it. Comparisons of the America of 2016 and Germany of 1933 proliferated, while denunciations of Republicans as Nazis or Nazi collaborators became common. It would be a worthwhile project for a student or scholar of American culture to cull through those statements and confront their authors with them today: if they were so wrong in 2016, what value is their judgment today, moving forward?

For those predictions were simply and utterly wrong. Of course, the Republican in the White House and the Republican-controlled Congress pursued a version of a conservative agenda (although not always with success, as in the case of health care). But the rule of law prevailed, courts could decide against the government, the liberal part of the press has been articulate in its critique of administration policies, and, in a quite normal and proper manner, the midterm elections took place. American institutions have proven much more robust than the hysterics of little faith claimed in 2016. Those prophets of dictatorship owe us an accounting—or actually an apology—for their hyperbole. They significantly trivialized what really happened under the Nazi dictatorship, and they cavalierly slandered that slightly less than half of the American electorate that voted for Trump. Time for some critical self-reflection? This is not at all a suggestion that they must endorse the president, but it is way past time for them to concede that his supporters are not a priori Nazis, no matter how much juvenile fun name-calling affords.

Continue reading →

|

|

Once upon a time, there was an illusion that the state would disappear. It was the fiction Marxists told each other at bedtime, and it was the lie of the Communists, once they had seized state power. For even as they built up their police apparatus and their archipelago of gulags, they kept promising that one day the state would eventually disappear.

Once upon a time, there was an illusion that the state would disappear. It was the fiction Marxists told each other at bedtime, and it was the lie of the Communists, once they had seized state power. For even as they built up their police apparatus and their archipelago of gulags, they kept promising that one day the state would eventually disappear.