By Ning Wang · Wednesday, September 13, 2017 Telos 180 (Fall 2017) is now available for purchase in our store.

In Western as well as international academia today, along with the acceleration of globalization more generally, humanities scholars have constructed a sort of theoretical discourse of globalization. In doing so, they have found it useful to refer to the old-fashioned philosophical concept of cosmopolitanism, which is very close to the theoretical construction of the discourse of globalization. Although it has previously been discussed over the history of Western philosophy, cosmopolitanism is once again a cutting-edge theoretical topic. The term nowadays frequently appears in the works of political philosophers and sociologists, and it is increasingly being taken up and debated by literary and cultural studies scholars as well, particularly with regard to the rise of world literature as the highest phase of comparative literature. Obviously, most of their work interprets and deals with cosmopolitanism from the perspectives of political philosophy and culture, while touching to some degree upon literary and cultural production and criticism. Moreover, most of the scholarship dealing with cosmopolitanism only occurs within a Western context. In this respect, the present special issue of Telos may well fill a gap in international cosmopolitanism scholarship. The recent interest in world literature in the field of comparative literature is undoubtedly associated with the rise of cosmopolitanism in the contemporary era. In the articles collected here, cosmopolitanism will mainly be addressed from literary and cultural perspectives, and, more importantly, they will move beyond the limits of Eurocentric or West-centric ways of thinking and modes of research by dealing exclusively with cosmopolitanism and China: its parallel relations with ancient Chinese philosophy, its impact on modern Chinese literature and intellectual thought, and its recent significance to China’s modernization and globalization. In Western as well as international academia today, along with the acceleration of globalization more generally, humanities scholars have constructed a sort of theoretical discourse of globalization. In doing so, they have found it useful to refer to the old-fashioned philosophical concept of cosmopolitanism, which is very close to the theoretical construction of the discourse of globalization. Although it has previously been discussed over the history of Western philosophy, cosmopolitanism is once again a cutting-edge theoretical topic. The term nowadays frequently appears in the works of political philosophers and sociologists, and it is increasingly being taken up and debated by literary and cultural studies scholars as well, particularly with regard to the rise of world literature as the highest phase of comparative literature. Obviously, most of their work interprets and deals with cosmopolitanism from the perspectives of political philosophy and culture, while touching to some degree upon literary and cultural production and criticism. Moreover, most of the scholarship dealing with cosmopolitanism only occurs within a Western context. In this respect, the present special issue of Telos may well fill a gap in international cosmopolitanism scholarship. The recent interest in world literature in the field of comparative literature is undoubtedly associated with the rise of cosmopolitanism in the contemporary era. In the articles collected here, cosmopolitanism will mainly be addressed from literary and cultural perspectives, and, more importantly, they will move beyond the limits of Eurocentric or West-centric ways of thinking and modes of research by dealing exclusively with cosmopolitanism and China: its parallel relations with ancient Chinese philosophy, its impact on modern Chinese literature and intellectual thought, and its recent significance to China’s modernization and globalization.

Continue reading →

By Russell A. Berman · Monday, June 15, 2015 Telos 171 (Summer 2015) is now available for purchase in our store.

Standard accounts of American politics invoke an oscillation between idealist and realist inclinations. The idealists appeal to principles, which they identify as fundamental to the American polity, especially those enshrined in the founding documents: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, transformed into a broad democratization agenda. Of course, revisionist critics have no difficulty in pointing out the failure of that agenda, i.e., the extent to which the empirical history of the country fell far short of realizing its ideals. Yet even that critique, smugly put forward to debunk naïve idealism, in some basic ways is itself indebted to the same idealism, insofar as the complaint of insufficient democratization also implies a call for more democracy, the very core of the idealist program. This is why neo-conservatives and their left-liberal adversaries always had more in common than met the eye (as was abundantly clear to traditional conservatives). Standard accounts of American politics invoke an oscillation between idealist and realist inclinations. The idealists appeal to principles, which they identify as fundamental to the American polity, especially those enshrined in the founding documents: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, transformed into a broad democratization agenda. Of course, revisionist critics have no difficulty in pointing out the failure of that agenda, i.e., the extent to which the empirical history of the country fell far short of realizing its ideals. Yet even that critique, smugly put forward to debunk naïve idealism, in some basic ways is itself indebted to the same idealism, insofar as the complaint of insufficient democratization also implies a call for more democracy, the very core of the idealist program. This is why neo-conservatives and their left-liberal adversaries always had more in common than met the eye (as was abundantly clear to traditional conservatives).

Continue reading →

By Jacob Dreyer · Thursday, May 29, 2014  In China as in the Soviet Union, it seemed particularly cruel to “political” prisoners that thieves, rapists, and murderers should be placed higher in the camp hierarchy than they were. From the perspective of the CCP, this often touched on the point of class origins, for of course the intellectual class often emerged from the urban bourgeoisie, whereas the common criminals come from the dodgy, poor neighborhoods or, in their rural equivalent, poor, burned-out villages. However, what the victorious revolutionaries sought to achieve was the laborious process of lifting the world off of its axle and inverting it, like a gigantic bureau drawer; of course all sorts of things fall out, and if they are delicate, shatter. The intellectual class was, and is, that class which had already begun lifting themselves out of the material world, on their own terms, with thought. For those authorities who wish to arrange a collective transfer of all resources and persons from the old world into a still unimaginable new one, this individualistic secession from the world is a most dangerous form of treason, in comparison to which the rapes, knifings, stolen bread, and liquor of the underclass are all too easy to forgive. For the latter are simply operating the system in their own disadvantaged way, with the same objectives, finally, as the capitalists and lords, whereas the thinkers seek to float away entirely. It is for this reason that in the camps, the political prisons were considered “external contradictions,” the criminals, “internal contradictions.” In China as in the Soviet Union, it seemed particularly cruel to “political” prisoners that thieves, rapists, and murderers should be placed higher in the camp hierarchy than they were. From the perspective of the CCP, this often touched on the point of class origins, for of course the intellectual class often emerged from the urban bourgeoisie, whereas the common criminals come from the dodgy, poor neighborhoods or, in their rural equivalent, poor, burned-out villages. However, what the victorious revolutionaries sought to achieve was the laborious process of lifting the world off of its axle and inverting it, like a gigantic bureau drawer; of course all sorts of things fall out, and if they are delicate, shatter. The intellectual class was, and is, that class which had already begun lifting themselves out of the material world, on their own terms, with thought. For those authorities who wish to arrange a collective transfer of all resources and persons from the old world into a still unimaginable new one, this individualistic secession from the world is a most dangerous form of treason, in comparison to which the rapes, knifings, stolen bread, and liquor of the underclass are all too easy to forgive. For the latter are simply operating the system in their own disadvantaged way, with the same objectives, finally, as the capitalists and lords, whereas the thinkers seek to float away entirely. It is for this reason that in the camps, the political prisons were considered “external contradictions,” the criminals, “internal contradictions.”

Continue reading →

By Jacob Dreyer · Tuesday, May 13, 2014  As has been observed about Russian and Japanese modernisms, Chinese modernism was initiated with a sense of lack: the contact with an Other civilization (e.g., that of the West) more capable of controlling reality, one more materially powerful. If revolution is a rupture with the past, the Chinese revolution constituted a rupture with a relationship to space that flowed through the subjective experience of poetry, and its replacement with an ongoing process of rationalization, mapping, understanding—one often initiated by colonizers, whether the Westerners in the treaty ports, or the Japanese in the North. In other words, a subject trained to interact with an environment on the basis of a tradition of poetry, painting, and landscape architecture, in which the self was holistically internalized into a larger built environment, was forced to confront an environment in the process of transformation: mountains became mines, forests became timber, and of course, humans became factory workers.[3] As has been observed about Russian and Japanese modernisms, Chinese modernism was initiated with a sense of lack: the contact with an Other civilization (e.g., that of the West) more capable of controlling reality, one more materially powerful. If revolution is a rupture with the past, the Chinese revolution constituted a rupture with a relationship to space that flowed through the subjective experience of poetry, and its replacement with an ongoing process of rationalization, mapping, understanding—one often initiated by colonizers, whether the Westerners in the treaty ports, or the Japanese in the North. In other words, a subject trained to interact with an environment on the basis of a tradition of poetry, painting, and landscape architecture, in which the self was holistically internalized into a larger built environment, was forced to confront an environment in the process of transformation: mountains became mines, forests became timber, and of course, humans became factory workers.[3]

Continue reading →

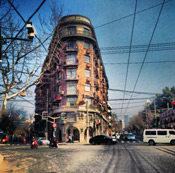

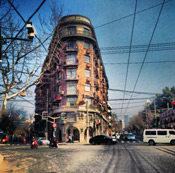

By Jacob Dreyer · Friday, May 2, 2014  For the outsider, the metropolis—a visual, tangible representation of the economic activities that it sites—appears to be endlessly seductive, complicated, and enthralling. And yet, for the urbanites themselves, both the skyline and the economy that it harbors inspire tedium; when will these games terminate, these spectacles that bring us no closer to a utopian community but merely run down the clock prior to the moment of judgment? What appears superficially to be busyness (e.g., business) is in fact a gigantic conspiracy for the wasting of everybody’s time, resources, and cognitive ability. At least, that is the way that it appeared to the revolutionary urban intellectuals of East Asia’s 1930s, both those from Tokyo as well as those from Shanghai; the former group, motivated by a critique of capitalism, would be involved in the creation of much of the built structure of an East Asian modern, while the latter became architects of the Chinese Communist Revolution. The revolutionary impulse of the Japanese progressives in Manchuria was realized as technocracy; however, deeper insecurities about the nature of capitalist modernity haunted the thoughts and work of the men who, while articulating a system of modern infrastructure across the Great Northern Wasteland, simultaneously brooded upon the limited and constricting nature of the society within which they existed. For the outsider, the metropolis—a visual, tangible representation of the economic activities that it sites—appears to be endlessly seductive, complicated, and enthralling. And yet, for the urbanites themselves, both the skyline and the economy that it harbors inspire tedium; when will these games terminate, these spectacles that bring us no closer to a utopian community but merely run down the clock prior to the moment of judgment? What appears superficially to be busyness (e.g., business) is in fact a gigantic conspiracy for the wasting of everybody’s time, resources, and cognitive ability. At least, that is the way that it appeared to the revolutionary urban intellectuals of East Asia’s 1930s, both those from Tokyo as well as those from Shanghai; the former group, motivated by a critique of capitalism, would be involved in the creation of much of the built structure of an East Asian modern, while the latter became architects of the Chinese Communist Revolution. The revolutionary impulse of the Japanese progressives in Manchuria was realized as technocracy; however, deeper insecurities about the nature of capitalist modernity haunted the thoughts and work of the men who, while articulating a system of modern infrastructure across the Great Northern Wasteland, simultaneously brooded upon the limited and constricting nature of the society within which they existed.

Continue reading →

By Jacob Dreyer · Monday, April 21, 2014 In this series of entries, Jacob Dreyer investigates the spatial forms of modernity in China, notably that of the Metropolis (e.g., Shanghai) and the Wasteland (e.g., Heilongjiang). In his last piece, he read the two regions through Schmitt’s dialectic of land and sea; here, he reads Shanghai through Dostoyevsky’s vision of the Crystal Palace; the next piece will subject the exterior, the “Great Northern Wasteland,” to a similar analysis.

If the goal of the project of modernity in China is ultimately the integration of the entire territory of PRC China into an urbanized “interior,” with no useless or wild zones, of universalizing the social practices of the metropolis, then an investigation into the unique spatial forms that did not emerge until modernity—and their shadow in consciousness, visible in the work of philosophers, writers, and architects—is necessary. As discussed in my previous post, Chinese literati have been exploring the territory since the beginning of civilization in Asia. In fact, it would not be inaccurate to say that the beginning of civilization is created by the initial architectural division between “inside” and “outside,”[1] created by architecture—physical edifices, no doubt, but also the structures of thought and language which tend to divide the world into two zones, interior and exterior. If the goal of the project of modernity in China is ultimately the integration of the entire territory of PRC China into an urbanized “interior,” with no useless or wild zones, of universalizing the social practices of the metropolis, then an investigation into the unique spatial forms that did not emerge until modernity—and their shadow in consciousness, visible in the work of philosophers, writers, and architects—is necessary. As discussed in my previous post, Chinese literati have been exploring the territory since the beginning of civilization in Asia. In fact, it would not be inaccurate to say that the beginning of civilization is created by the initial architectural division between “inside” and “outside,”[1] created by architecture—physical edifices, no doubt, but also the structures of thought and language which tend to divide the world into two zones, interior and exterior.

Continue reading →

|

|

In Western as well as international academia today, along with the acceleration of globalization more generally, humanities scholars have constructed a sort of theoretical discourse of globalization. In doing so, they have found it useful to refer to the old-fashioned philosophical concept of cosmopolitanism, which is very close to the theoretical construction of the discourse of globalization. Although it has previously been discussed over the history of Western philosophy, cosmopolitanism is once again a cutting-edge theoretical topic. The term nowadays frequently appears in the works of political philosophers and sociologists, and it is increasingly being taken up and debated by literary and cultural studies scholars as well, particularly with regard to the rise of world literature as the highest phase of comparative literature. Obviously, most of their work interprets and deals with cosmopolitanism from the perspectives of political philosophy and culture, while touching to some degree upon literary and cultural production and criticism. Moreover, most of the scholarship dealing with cosmopolitanism only occurs within a Western context. In this respect, the present special issue of Telos may well fill a gap in international cosmopolitanism scholarship. The recent interest in world literature in the field of comparative literature is undoubtedly associated with the rise of cosmopolitanism in the contemporary era. In the articles collected here, cosmopolitanism will mainly be addressed from literary and cultural perspectives, and, more importantly, they will move beyond the limits of Eurocentric or West-centric ways of thinking and modes of research by dealing exclusively with cosmopolitanism and China: its parallel relations with ancient Chinese philosophy, its impact on modern Chinese literature and intellectual thought, and its recent significance to China’s modernization and globalization.

In Western as well as international academia today, along with the acceleration of globalization more generally, humanities scholars have constructed a sort of theoretical discourse of globalization. In doing so, they have found it useful to refer to the old-fashioned philosophical concept of cosmopolitanism, which is very close to the theoretical construction of the discourse of globalization. Although it has previously been discussed over the history of Western philosophy, cosmopolitanism is once again a cutting-edge theoretical topic. The term nowadays frequently appears in the works of political philosophers and sociologists, and it is increasingly being taken up and debated by literary and cultural studies scholars as well, particularly with regard to the rise of world literature as the highest phase of comparative literature. Obviously, most of their work interprets and deals with cosmopolitanism from the perspectives of political philosophy and culture, while touching to some degree upon literary and cultural production and criticism. Moreover, most of the scholarship dealing with cosmopolitanism only occurs within a Western context. In this respect, the present special issue of Telos may well fill a gap in international cosmopolitanism scholarship. The recent interest in world literature in the field of comparative literature is undoubtedly associated with the rise of cosmopolitanism in the contemporary era. In the articles collected here, cosmopolitanism will mainly be addressed from literary and cultural perspectives, and, more importantly, they will move beyond the limits of Eurocentric or West-centric ways of thinking and modes of research by dealing exclusively with cosmopolitanism and China: its parallel relations with ancient Chinese philosophy, its impact on modern Chinese literature and intellectual thought, and its recent significance to China’s modernization and globalization.  Standard accounts of American politics invoke an oscillation between idealist and realist inclinations. The idealists appeal to principles, which they identify as fundamental to the American polity, especially those enshrined in the founding documents: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, transformed into a broad democratization agenda. Of course, revisionist critics have no difficulty in pointing out the failure of that agenda, i.e., the extent to which the empirical history of the country fell far short of realizing its ideals. Yet even that critique, smugly put forward to debunk naïve idealism, in some basic ways is itself indebted to the same idealism, insofar as the complaint of insufficient democratization also implies a call for more democracy, the very core of the idealist program. This is why neo-conservatives and their left-liberal adversaries always had more in common than met the eye (as was abundantly clear to traditional conservatives).

Standard accounts of American politics invoke an oscillation between idealist and realist inclinations. The idealists appeal to principles, which they identify as fundamental to the American polity, especially those enshrined in the founding documents: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, transformed into a broad democratization agenda. Of course, revisionist critics have no difficulty in pointing out the failure of that agenda, i.e., the extent to which the empirical history of the country fell far short of realizing its ideals. Yet even that critique, smugly put forward to debunk naïve idealism, in some basic ways is itself indebted to the same idealism, insofar as the complaint of insufficient democratization also implies a call for more democracy, the very core of the idealist program. This is why neo-conservatives and their left-liberal adversaries always had more in common than met the eye (as was abundantly clear to traditional conservatives).  In China as in the Soviet Union, it seemed particularly cruel to “political” prisoners that thieves, rapists, and murderers should be placed higher in the camp hierarchy than they were. From the perspective of the CCP, this often touched on the point of class origins, for of course the intellectual class often emerged from the urban bourgeoisie, whereas the common criminals come from the dodgy, poor neighborhoods or, in their rural equivalent, poor, burned-out villages. However, what the victorious revolutionaries sought to achieve was the laborious process of lifting the world off of its axle and inverting it, like a gigantic bureau drawer; of course all sorts of things fall out, and if they are delicate, shatter. The intellectual class was, and is, that class which had already begun lifting themselves out of the material world, on their own terms, with thought. For those authorities who wish to arrange a collective transfer of all resources and persons from the old world into a still unimaginable new one, this individualistic secession from the world is a most dangerous form of treason, in comparison to which the rapes, knifings, stolen bread, and liquor of the underclass are all too easy to forgive. For the latter are simply operating the system in their own disadvantaged way, with the same objectives, finally, as the capitalists and lords, whereas the thinkers seek to float away entirely. It is for this reason that in the camps, the political prisons were considered “external contradictions,” the criminals, “internal contradictions.”

In China as in the Soviet Union, it seemed particularly cruel to “political” prisoners that thieves, rapists, and murderers should be placed higher in the camp hierarchy than they were. From the perspective of the CCP, this often touched on the point of class origins, for of course the intellectual class often emerged from the urban bourgeoisie, whereas the common criminals come from the dodgy, poor neighborhoods or, in their rural equivalent, poor, burned-out villages. However, what the victorious revolutionaries sought to achieve was the laborious process of lifting the world off of its axle and inverting it, like a gigantic bureau drawer; of course all sorts of things fall out, and if they are delicate, shatter. The intellectual class was, and is, that class which had already begun lifting themselves out of the material world, on their own terms, with thought. For those authorities who wish to arrange a collective transfer of all resources and persons from the old world into a still unimaginable new one, this individualistic secession from the world is a most dangerous form of treason, in comparison to which the rapes, knifings, stolen bread, and liquor of the underclass are all too easy to forgive. For the latter are simply operating the system in their own disadvantaged way, with the same objectives, finally, as the capitalists and lords, whereas the thinkers seek to float away entirely. It is for this reason that in the camps, the political prisons were considered “external contradictions,” the criminals, “internal contradictions.”  As has been observed about Russian and Japanese modernisms, Chinese modernism was initiated with a sense of lack: the contact with an Other civilization (e.g., that of the West) more capable of controlling reality, one more materially powerful. If revolution is a rupture with the past, the Chinese revolution constituted a rupture with a relationship to space that flowed through the subjective experience of poetry, and its replacement with an ongoing process of rationalization, mapping, understanding—one often initiated by colonizers, whether the Westerners in the treaty ports, or the Japanese in the North. In other words, a subject trained to interact with an environment on the basis of a tradition of poetry, painting, and landscape architecture, in which the self was holistically internalized into a larger built environment, was forced to confront an environment in the process of transformation: mountains became mines, forests became timber, and of course, humans became factory workers.[3]

As has been observed about Russian and Japanese modernisms, Chinese modernism was initiated with a sense of lack: the contact with an Other civilization (e.g., that of the West) more capable of controlling reality, one more materially powerful. If revolution is a rupture with the past, the Chinese revolution constituted a rupture with a relationship to space that flowed through the subjective experience of poetry, and its replacement with an ongoing process of rationalization, mapping, understanding—one often initiated by colonizers, whether the Westerners in the treaty ports, or the Japanese in the North. In other words, a subject trained to interact with an environment on the basis of a tradition of poetry, painting, and landscape architecture, in which the self was holistically internalized into a larger built environment, was forced to confront an environment in the process of transformation: mountains became mines, forests became timber, and of course, humans became factory workers.[3]  For the outsider, the metropolis—a visual, tangible representation of the economic activities that it sites—appears to be endlessly seductive, complicated, and enthralling. And yet, for the urbanites themselves, both the skyline and the economy that it harbors inspire tedium; when will these games terminate, these spectacles that bring us no closer to a utopian community but merely run down the clock prior to the moment of judgment? What appears superficially to be busyness (e.g., business) is in fact a gigantic conspiracy for the wasting of everybody’s time, resources, and cognitive ability. At least, that is the way that it appeared to the revolutionary urban intellectuals of East Asia’s 1930s, both those from Tokyo as well as those from Shanghai; the former group, motivated by a critique of capitalism, would be involved in the creation of much of the built structure of an East Asian modern, while the latter became architects of the Chinese Communist Revolution. The revolutionary impulse of the Japanese progressives in Manchuria was realized as technocracy; however, deeper insecurities about the nature of capitalist modernity haunted the thoughts and work of the men who, while articulating a system of modern infrastructure across the Great Northern Wasteland, simultaneously brooded upon the limited and constricting nature of the society within which they existed.

For the outsider, the metropolis—a visual, tangible representation of the economic activities that it sites—appears to be endlessly seductive, complicated, and enthralling. And yet, for the urbanites themselves, both the skyline and the economy that it harbors inspire tedium; when will these games terminate, these spectacles that bring us no closer to a utopian community but merely run down the clock prior to the moment of judgment? What appears superficially to be busyness (e.g., business) is in fact a gigantic conspiracy for the wasting of everybody’s time, resources, and cognitive ability. At least, that is the way that it appeared to the revolutionary urban intellectuals of East Asia’s 1930s, both those from Tokyo as well as those from Shanghai; the former group, motivated by a critique of capitalism, would be involved in the creation of much of the built structure of an East Asian modern, while the latter became architects of the Chinese Communist Revolution. The revolutionary impulse of the Japanese progressives in Manchuria was realized as technocracy; however, deeper insecurities about the nature of capitalist modernity haunted the thoughts and work of the men who, while articulating a system of modern infrastructure across the Great Northern Wasteland, simultaneously brooded upon the limited and constricting nature of the society within which they existed.  If the goal of the project of modernity in China is ultimately the integration of the entire territory of PRC China into an urbanized “interior,” with no useless or wild zones, of universalizing the social practices of the metropolis, then an investigation into the unique spatial forms that did not emerge until modernity—and their shadow in consciousness, visible in the work of philosophers, writers, and architects—is necessary. As discussed in my previous post, Chinese literati have been exploring the territory since the beginning of civilization in Asia. In fact, it would not be inaccurate to say that the beginning of civilization is created by the initial architectural division between “inside” and “outside,”[1] created by architecture—physical edifices, no doubt, but also the structures of thought and language which tend to divide the world into two zones, interior and exterior.

If the goal of the project of modernity in China is ultimately the integration of the entire territory of PRC China into an urbanized “interior,” with no useless or wild zones, of universalizing the social practices of the metropolis, then an investigation into the unique spatial forms that did not emerge until modernity—and their shadow in consciousness, visible in the work of philosophers, writers, and architects—is necessary. As discussed in my previous post, Chinese literati have been exploring the territory since the beginning of civilization in Asia. In fact, it would not be inaccurate to say that the beginning of civilization is created by the initial architectural division between “inside” and “outside,”[1] created by architecture—physical edifices, no doubt, but also the structures of thought and language which tend to divide the world into two zones, interior and exterior.