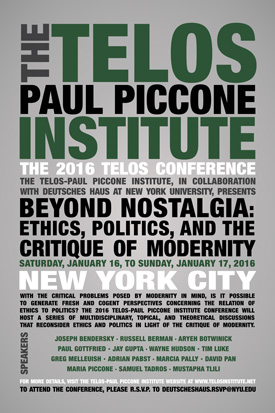

The following paper was presented at the 2016 Telos Conference, held on January 16–17, 2016, in New York City. For additional details about the conference, please visit the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute website.

Introduction

Introduction

State institutions, starting with the entity we call “the state” all the way down to city DMV offices, seem no longer capable of acting or behaving ethically, regardless of what type of ethics we prefer to apply to politics—consequentialist, deontological, virtue, or any other—or whether we prefer liberal or communitarian normative agendas. Two features of modern political institutions block their intended functioning, ethical or not, and lead to new ethical crises. Those features are too-large size and incoherence. Thus even when policies[1] are ethical, institutions’ failures to implement or follow them undermine an ethical politics. And when various policies are implemented unevenly, new ethical problems arise. At least a partial antidote to these problems may be found in libertarian municipalism, the social-ecological approach articulated by Murray Bookchin, that demands small scale and direct democracy.

What is Oversize?

Frequently, institutional problems are seen as problems of (upward) scalability, the darling of efficiency. Adopted solutions are supposed to allow a greater number of functions to occur at once and with minimal human effort, and therefore to fulfill institutional goals and implement policies more efficiently, effectively, and equitably. We’ve arrived at the main problem: the “cult of bigness,” as articulated by Leopold Kohr.[2] Although Kohr specifically indicts whole states, the insight applies just as well to political institutions in general.[3] In the context of intra-national political institutions, too-large size creates steeply layered, disorganized hierarchy-anarchies, whose colossal bureaucracies “terrorize” internal and external participants.

What is Incoherence?

Political institutions are not rational systems, and are best explained by the Garbage Can Theory of organizations (GCT).[4] GCT treats organizations as stages for decision-making that are organized anarchies.[5] The central insight of this theory is that solutions and problems, resources and needs, and actions and actors, get matched up anachronistically and rather coincidentally in an opaque institutional setting (the “garbage can”). Thus institutional behavior is marked by significant irrationality, by ad hoc approaches, and by inconsistency.

Logistical Consequences of Oversize and Incoherence

Inefficiency

When institutional acts or functions degrade, the institution’s ability to meet its purpose degrades, rendering policy content, ethical or not, moot. So institutional inadequacy stems from institutional oversize. According to Kohr,

At critical size, the survival requirements of society begin to increase at a faster rate than its productivity. As a result, an ever increasing proportion of goods which were previously available for raising personal living standards must now be diverted to social use.[6]

To adapt this argument to institutions: At critical size, the survival requirements of the institution begin to increase at a faster rate than its productivity. As a result, an ever increasing proportion of goods, which were previously available for implementing policies must now be diverted to institutional use[7] For example, in many settings, the gains in efficiency that result from electronic self-service must be paid for with the provision of telecommunications infrastructure, and a department devoted to maintaining it. This is to say nothing of the dependence on the broad adoption of personal electronic devices, national utilities regulations and oversight, national utilities security, and economies related to the procurement of the raw materials and for the research and development required for the technologies.

Opacity

In addition, oversize leads to institutional opacity. One form of this occurs when the “right arm” of an institution does not know what the “left arm” is doing. Sheer institutional distance between one department and another makes coordination of functions difficult. It also increases the “transactional cost” of coordination.[8] Additional administrative layers or processes are often introduced to address such problems, but this only grows the institution further and continues to gulp resources that may have been used to implement policies more directly.

Steepened Hierarchy

Oversize and incoherence steepen hierarchy because administrative layers and processes are routinely added to institutions. Ironically, this is frequently done in attempts to solve problems stemming from oversize and incoherence. Thus institutions’ power grows ever greater relative to that of its external participants. This puts decision-makers out of reach of the public. The public is relegated to interacting with a firewall, either in the form of administrators who themselves have no access to a decision-maker who could, for instance, change or break institutional rules when it was appropriate, or in the form of technology that specifically insulates institutional decision-makers.

Ethical Consequences of Oversize and Incoherence

Alienation

Institutional incoherence and too-large size lead to wholly new ethical problems. One such problem is alienation, by which I mean an alienation of the citizenry from the public institutions of which they are a part. Institutions attempt to deploy an instrumental rationality that targets and occasionally solves administrative problems, but is incapable of defining or pursuing humanistic priorities. Thus, in the best of circumstances, large institutions respond to statistics rather than people. The gaps between their deployed solutions and the needs of the people they serve reflect their shortcomings—the extent to which they alienate.

This alienation is no trivial thing—it’s the stuff of separatist movements and terrorist attacks, “failure” to live in society as peaceable and productive citizens, and even generational cynicism and depression. Perhaps it is simply the glazed-over and coerced feeling we get when forced to “press 3 to return to the main menu” or read technical manuals in order to interact with an institution as a result of its adopted processes, neither of which allows us to complete our intended task. The inability to communicate with and reach the very institutions that shape and even determine our lives is at least frustrating. When this inability is absolute or when it concerns more versus less critical problems, more extreme social responses emerge. These are the responses that prompt us to search for an ethical politics in the first place.

In addition, those that are required to interact with “the outside” lack the authority to make adjustments to institutional processes in response to public needs. If tribalist theories about the limits of human empathy have any merit,[9] we can infer that a failure to know more rather than less intimately the people impacted by one’s actions or by institutional actions, divests behaviors of ethics. If one’s behaviors or the results of the policies that one enforces always appear victimless or inconsequential, there is little incentive to change tacks.

Lastly, there are implications for internal members of the institution. Irrational, ad hoc, and inconsistent approaches to institutional work alienate internal participants who must deal with the administrative fallout of such processes. Arguably, some form of rationality, empathy, or self-determination is a part of human species-being,[10] which participants are pre-empted from enacting in incoherent institutions.

Injustice

It requires quite little scale for scaled “solutions” to fail to serve participants in all but the most standard, “average” circumstances; functions are presumed to occur in the service of abstract persons, and this, far from granting a Rawlsian justice of sorts, manages not to capture a great many individuals. Participants must go to great lengths to gain the services promised by the institution, if the function they depend on an institution to fulfill is impossible to accomplish through “scaled” means. This represents a type of labor “offshoring”: institutions simply offload administrative labor onto individual external participants.

Agenda: Libertarian Municipalism, Social Ecology, and Bioregionalism

To ensure institutional candidacy for ethical behavior, institutional incoherence and oversize must be addressed. And there is a conceptual approach to addressing them. Murray Bookchin has articulated a normative social-ecological theory of political life in the form of libertarian municipalism. Libertarian municipalism suggests the adoption of direct democracy on a small enough scale that it fosters personal accountability to those impacted by democratic decisions.

In this context, libertarianism references the retention of individual freedom and stands in opposition to communitarian prescriptions. Municipalism necessarily references smallness. It proposes political associations based on “members qua residents,”[11] rather than on less organic groupings, in order to retain human familiarity that leads to a human-based politics on a human scale. According to Kirkpatrick Sale, a bioregional polity would provide, “more points of access for the citizens, more points of pressure for affected minorities.”[12] The point of heterarchical institutional organization is to undermine relations of what Sale calls “command-obediance” as are found in hierarchical institutions—that is what is meant by the word freedom in “the ecology of freedom.”[13]

For Bookchin, bringing biological-natural phenomena into accord with the social-natural means that political institutions, uniquely human entities, must function according to ecological principles.[14] Such principles necessitate relinquishing the belief in the potential for endless growth—an ecological impossibility. Some may argue that such an approach is unrealistic. But that doesn’t change the correctness of the diagnosis or treatment.

Notes

1. I use the term “policy” broadly throughout this work to refer to policies that guide or specify political institutional agendas (e.g., that the United States Bureau of Engraving and Printing prints money according to certain guidelines), as well as that identify institutions as such (e.g., that the United States Bureau of Engraving and Printing exists as an institution for printing money), and that specify political systems in general (that money is a means of exchange).

2. Leopold Kohr, The Breakdown of Nations (Cambridge: Green Books, 2001; originally published in London: Kegan Paul, 1957); Leopold Kohr, The Overdeveloped Nations: The Diseconomies of Scale (New York: Schoken Books, 1978).

3. Leopold Kohr, “Disunion Now,” Commonweal (1941): 540–42. Originally published under the pseudonym Hans Kohr.

4. Michael Cohen, James March, and Johan Olsen, “A Garbage Can Model of Organizational Choice,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 17.1 (1972): 1–25.

5. GCT uses academic institutions as an example of such organizations, but GCT describes other state institutions just as well. See Guido Fioretti and Alessandro Lomi, “Passing the Buck in the Garbage Can Model Of organizational Choice,” Computational and Mathematical Organization Theory, 16.2 (2010): 113–43.

6. Leopold Kohr, “Critical Size,” in The Overdeveloped Nations: The Diseconomies of Scale (New York: Schoken Books, 1978), 5. The italics occur in the original.

7. For self-maintenance and/or self-preservation.

8. For “transactional cost,” see Kohr, The Overdeveloped Nations.

9. See, for instance, Stephen Asma, “The Biological Limits of Empathy,” The RSA Journal (Summer 2013): 10–15.

10. Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 (New York: International Publishers, 1964). The concept of species-being (Gattungswesen) was adapted from Ludwig Feuerbach.

11. Janet Biehl, “The Municipality,” in The Politics of Social Ecology: Libertarian Municipalism (New York: Black Rose Books, 1998), 54. Bookchin was not the first to suggest smallness or call for a human scale to political life. Kohr argued for small states, and for smallness in general. However, he didn’t frame his prescriptions in ecological terms, which I believe provide a much-needed foundation to conceptions of appropriate scale and proportion.

12. Kirkpatrick Sale, Dwellers in the Land: The Bioregional Vision (San Francisco: Sierra Club, 1985), 96.

13. Ibid., 101.

14. Murray Bookchin, The Ecology of Freedom: The Emergence and Dissolution of Hierarchy (New York: Black Rose Books, 1991). “First nature” and “second nature” are the terms Bookchin uses to discuss the distinction between the biological versus the social, although he doesn’t see these as being in opposition to one another or in an additive way.