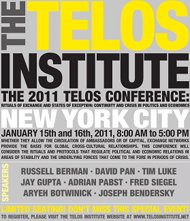

This paper was presented at the 2011 Telos Conference, “Rituals of Exchange and States of Exception: Continuity and Crisis in Politics and Economics.”

Slavoj Žižek poses more than a few heavy-gauge questions in his In Defense of Lost Causes. Foremost among them, at the beginning of chapter nine: “The only true question today is: do we endorse this ‘naturalization’ of capitalism, or does contemporary global capitalism contain antagonisms which are sufficiently strong to prevent its infinite reproduction?” (421). This vast question—as well as its possible answers—develops in many ways out of the discussion in the previous chapter of the book, in which Žižek approaches Alain Badiou’s concepts of subtraction and the Event with his usual copious verve, as well as with substantial concern that Badiou’s “subtraction” means that one might have the capacity to stand “outside” the “state form,” but only in a way that is “not destructive of the state form” (402). Žižek thus concludes that Badiou has

Slavoj Žižek poses more than a few heavy-gauge questions in his In Defense of Lost Causes. Foremost among them, at the beginning of chapter nine: “The only true question today is: do we endorse this ‘naturalization’ of capitalism, or does contemporary global capitalism contain antagonisms which are sufficiently strong to prevent its infinite reproduction?” (421). This vast question—as well as its possible answers—develops in many ways out of the discussion in the previous chapter of the book, in which Žižek approaches Alain Badiou’s concepts of subtraction and the Event with his usual copious verve, as well as with substantial concern that Badiou’s “subtraction” means that one might have the capacity to stand “outside” the “state form,” but only in a way that is “not destructive of the state form” (402). Žižek thus concludes that Badiou has

recently relegated capitalism to the naturalized “background” of our historical constellation: capitalism as “worldless” is not part of a specific situation, it is the all-encompassing background against which particular situations emerge. This is why it is senseless to pursue “anti-capitalist politics.” (403)

So much, perhaps, for revolution? Not, of course, if we are interested, as both Žižek and Badiou remain, in the content of the concept “communism.” Nonetheless Žižek proposes that resistance, and perhaps revolution, must become less abstract, and must be targeted at smaller-scale, concrete institutions rather than immense concepts. As he ventriloquizes Badiou: “One does not fight ‘capitalism,’ one fights the US government, its decisions and measures and so on” (403).

Chapter nine of In Defense of Lost Causes elaborates extensively on the issue of the “naturalization” of capitalism, how it functions metaphorically and symbolically, and the ways in which such rhetoric falsely represents and distends political economy. Žižek chooses four “antagonisms” through which to draw out his analysis of naturalized capitalism. All four are bio-political, for they derive from the possibility of tangible or intangible disaster based on interventions into living and social systems: first, “ecological catastrophe” (421); second the problem of biological material as property, that is “genetic components . . . owned by others” (422); third, the evacuation of “ethics as such” through its compression into subforms contingent upon interventions into living systems, like environmental ethics, bioethics, or medical ethics (423); and, finally, “new forms of apartheid” based on political considerations that may or may not be proxies for race (423).

Significant in Žižek’s analysis—and also related to his conversation with Badiou—is that it remains haunted everywhere with the specter of subjectivity. In Žižek’s inimitably virtuosic Lacanian fashion, that subjectivity may be perilously close to vestigial given that its agency is constrained and threatened by the emanations of both “global capitalism” and “catastrophe.” Nonetheless both Žižek and Badiou leave little doubt that it should retain some kind of grounding, even if that grounding emerges through the negative. Žižek thus criticizes Simon Critchley at length in his chapter on “The Crisis of Determinate Negation” for misreading Badiou and Lacan, going so far as to say, with ringing positivity in the negative claim, that Critchley’s form of argument “is an almost perfect embodiment of the position to which my work is absolutely opposed” (339). For Žižek this is because Critchley, in his falsely Badiouian quiescence about the naturalization of capitalism, evacuates the significance—and autonomy—of the subject, making it into an artifact of the pursuit of some capital-G Good. Badiou in fact uses the concept “autonomy” quite straightforwardly, and Žižek follows him in doing so, quoting a 2007 interview in which Badiou identifies “subtraction” directly with the sphere of subjective autonomy:

What subtraction does is bring about a point of autonomy. It’s a negation, but it cannot be identified with the properly destructive part of negation. . . . We need an “originary subtraction” capable of creating a new space of independence and autonomy from the dominant laws of the situation. (407)

Thence emerges some of Žižek’s tarrying with the positive in his attempt to navigate around Badiou’s creeping naturalization of capitalism in a way that nonetheless retains the suggestion that individuals pursue forms of highly specific resistance. In one of the most positive of his formulations, which emerges directly from his critique of Critchley’s arguments about subjectivity and resistance: “it is necessary to bombard those in power with . . . precise, finite demands . . .” (350).

Žižek’s analysis, and that of so many commentators upon the vagaries of twenty-first century quasi-democratic politics, seems to me nonetheless, to be missing a crucial element. Where Žižek seems to posit a kind of reconvergence, dialectical or otherwise, of the classical autonomous subject of the liberal and Frankfurt School traditions with the class-based vocabulary of more radical Marxist and poststructuralist analyses, I see another layer (a layer further approached in several branches recent queer theory, like that of David Halperin, Tim Dean, and Lee Edelman): the subject under the condition of the risk pool. The risk pool, protean and ubiquitous in today’s finance capital–driven political economy, takes form in those meta-structures of institutionalized financial, political, and medical (i.e., bio-political) insurance and quasi-insurance that do not so much control the subject’s spheres of activity as regulate them through positive and negative incentive and payoff. I suggest, in fact, that the content of the political in the Western post-industrial welfare-state economies has been swallowed by the administrative functions of risk pooling. Pension insurance and meta-insurance; the baroque emanations of Western health insurance systems; defense and military spending; public health interventions from anti-smoking campaigns to safer sex; food, drug, and medical device regulation; consumer product safety standards; environmental protection standards and carbon emission regulation regimes; primary and secondary infrastructural investment . . .

All of these are varied forms of risk pooling in the name of public policy, for they require sometimes substantial up-front investment in the hope of benefit later, either as positive payoff or the potential mitigation of serious negative consequences, some represented with rhetorical intensity ranging up to the near-apocalyptic, like climate change and terrorism (in particular of the nuclear variety that retains at least a frisson of Cold War–era Mutual Assured Destruction). All also belong to the sphere of probabilistic calculation, whether the form of that calculation is demographic, actuarial, or financial. We may not be able to tell when any individual will die. But we know with the only kind of certainty that very few human beings will live past the age of 100. Thus the fundamental difference between risk, which is calculable and therefore somewhat predictable, and uncertainty, which is contingent and therefore not calculable—a distinction that has exercised social scientists at length, and which took its first extensively elaborated form in economic thought in Frank Knight’s 1921 Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit.

I believe that this dominance of risk pooling in the functions of administration and government (to speak nothing of the private sector) has vast consequences for political-economic subjectivity, consequences that have only begun to be explored. We see most dramatically the gap in this understanding through the varied forms of generally conservative political thought that seem to cling to agency as something constituted by its relationship to uncertainty. Hence the fetishization of everything from guns to immense financial bets in certain branches of political thought. Telos is an ideal place, of course, to explore how such claims relate to many politically heterodox branches of twentieth-century thought, like some of that of Carl Schmitt, Ernst Jünger, and even Walter Benjamin, that seems to demand a subject that in common parlance “takes risks,” but in the political-economic vocabulary of the analysis here seems to take a particular interest is his or her relationship to uncertainty. Remarkably, in political discourse in the United States, one common emanation of this kind of fetishization of uncertainty is derision for what is perceived to be too much risk pooling, because it appears to evacuate the possibility for authentic subjective experience. This, I believe, is the source of much of the symbolic power of neo-liberal “deregulation” and its discursive avatars, those who do things like drive the loathing expressed toward the recent health-care reform legislation in the United States. Sarah Palin’s recent defense of rhetorical violence is only one of many branches of these discourses. We see them everywhere in the double-faced loathing expressed toward everything from polymorphous sexuality or smoking (as representations of “risky” behavior in which aggregate risk in a population may be calculable, but the consequences for individuals are always uncertain), or (for its failure as risk-mitigating institution) toward one of the strangest amalgams of military-industrial-civil risk pooling, the United States Army Corps of Engineers, in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.

Žižek’s In Defense of Lost Causes approaches something like these claims only once. In his chapter on Badiou’s subtraction, he links the naturalization of capitalism to something he calls “a reflexive risk society”:

So, one can say that we should indeed assert that, today, though history is not at an end, the very notion of “historicity” functions in a different way than before. What this means is that, paradoxically, the “renaturalization” of capitalism and the experience of our society as a reflexive risk society in which phenomena are experienced as contingent, as the result of a historically contingent construction, are two sides of the same coin. (405)

Žižek does thank the Indian political scientist Saroj Giri—an analyst of the Maoist movements in West Bengal—for stimulating these thoughts. I am still trying to figure them out. So, it seems, is Žižek.

My preliminary conclusion, however, is that the (voluntarily or involuntarily) risk-pooled human being is therefore in many ways neither subject nor class. She is always both, and navigating always between them in the sphere of financially, actuarially, and demographically mediated risk. Such navigation in many ways evacuates the forms of political agency posited in both liberal and Marxist traditions, and focuses the individual centrally on the problem of uncertainty—the possibility that certain factors remain outside the sphere of the insurable—a problem that at once redoubles the symbolic function of the fear of uncertainty in political discourse and makes a fetish of it. It makes out of queer people a marker of that uncertainty, it makes out of government policy an always-already of the failure—even in any attempt—to protect any and all against anything and everything, turning class into both suspect classification and actuarial pool, and it thereby makes of the self a kind of property. Risk pooling, it seems, more radically and subtly reifies the political-economic subject than any kind of either wage-labor exploitation or revolutionary consciousness. This tension between subject and class even causes an otherwise serious commentator like Niall Ferguson (Davos-ready spokesman for finance capital that he may be), in his The Ascent of Money, to revert to a Darwinesque metaphor that shows more than the rhetorical stakes of the problem, and which he devolves—willingly and with subtly infinite rhetorical violence—onto Joseph Schumpeter: “This economic system cannot do without the ultima ratio of the complete destruction of those existences which are irretrievably associated with the hopelessly unadapted” (357).

The author wishes to thank all of the organizers and participants of the 2009 and 2011 Telos Conferences in New York City for their contributions to the development and refinement of these thoughts.