If a journal manages to survive for 100 issues, it is reasonable to assume that the editorial board has managed to reach some sort of internal consensus and can finally rest on its laurels. Such is not the case with Telos. . . . After all these years, nothing seems to be settled and [Telos] remains a hopelessly heterogeneous group still trying to come to some agreement concerning many crucial and not-so-crucial issues. . . . This is why this theoretical bellum omnium contra omnes may be interpreted as evidence of lingering internal vitality, an unwillingness to take anything for granted, and a suspicion of all positions even faintly resembling conformism and passivity.

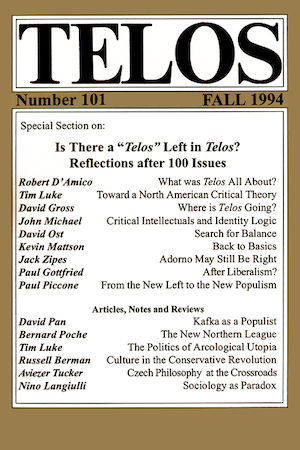

With those words from Telos 101 (Fall 1994), Paul Piccone launched his critique of those who felt Telos had lost its direction and had settled into the role of the cranky old uncle of intellectual journals. Having just celebrated its 200th issue in its 54th year, those words still speak to the current state of the intellectual project he launched back in 1968.

With those words from Telos 101 (Fall 1994), Paul Piccone launched his critique of those who felt Telos had lost its direction and had settled into the role of the cranky old uncle of intellectual journals. Having just celebrated its 200th issue in its 54th year, those words still speak to the current state of the intellectual project he launched back in 1968.

Piccone’s critique of his critics, “From the New Left to the New Populism,” was intended not to lay claim to any settled doctrine for Telos but to demonstrate the journal’s ability to constantly rethink its position among current debates along the entire ideological spectrum. While the bellum omnium contra omnes Piccone refers to in his article specifically refers to Telos‘s own family, I think it is more than fair to say it was applied to any and all who asserted a suspicious and artificial ground for emancipation. Toward this end, Piccone begins by providing his own critique of the Western Marxist tradition out of which Telos arose. This in itself, in its pure compactness, is a tour de force of intellectual history and should be read by all those who seek an origin story, or who simply need to have their revision revised.

What emerged from Telos fundamentally was an ongoing project to understand the current logic of domination while vindicating the search for subjectivity. In the process, it came to terms with the fact that it had to confront the historical situation with a political theory that the Western Marxist tradition always lacked, lost as it was in the belief that capitalism would eventually collapse from its own contradictions and a revolutionary class spearheaded by a party or an enlightened group could just step in to fill the void. What that tradition failed to see was that the political institutions on which capitalism found its legal and ethical existence were not just an ideological superstructure. Rather, as Gramsci tried to point out, it resonated with a cultural and pedagogical presence that provided its own rationality for itself that was independent of the logic of capital. The tradition out of which Western Marxism arose failed to incorporate the historical political logic necessary to understand the ethical and legal frameworks that defined injustice, inequality, and domination as fairness, opportunity, and independence. Critical Theory was no less problematic in this area. While some of its fellow travelers, e.g., Neumann and Kirchheimer, attempted to deal with the collapse of the legal state with the rise of Nazism, they remained caught up in a social democratic program that could not be adapted to the United States once they emigrated here. At the same time, any of the pathologies that program sought to address were lost in the prosperity of the postwar era and the Great Society programs that followed. Meanwhile, some in the group, such as Adorno, found solace in the Absolute Spirt, which failed to bring along an emancipatory interest with it. Others, such as Marcuse and Fromm, asserted a psychoanalysis that sought to understand social pathologies from the viewpoint of psychological repression, which when all is said and done is the repression of the transcendental ego. In short, psychoanalysis was trapped in the same solipsism that trapped Kant and Fichte. As Piccone’s article points out, all these projects collapsed. None of them could really explain the current logic of domination or provide a subjective foundation. None of them could provide a way for “the dialectic of subject and object [to postulate] the viability of a social system as a function of its internalization by the members living within it as active citizens.” If there ever was a program for Telos, it was the search for “an organic view of individuality, i.e., subjectivity constituted by the social and historical relations within which it is embedded.”

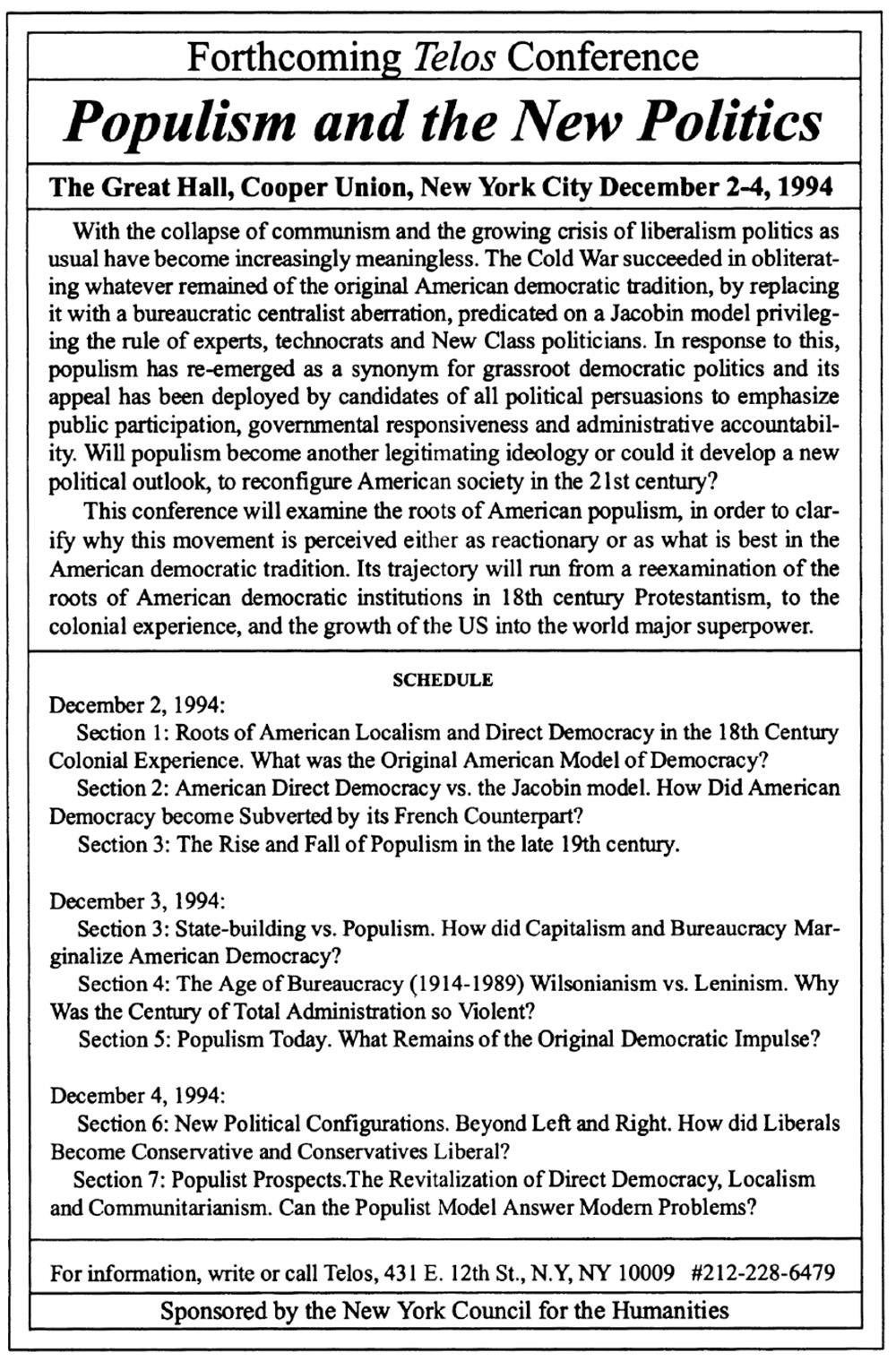

Telos Conference on “Populism and the New Politics”

December 2–4, 1994, in New York City

@ Telos Press Publishing. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

In its search for the “primacy of the subjective dimension and the need to constantly reconstitute the given,” Telos looked to Gouldner’s theories of the New Class to explain the mediating element of current strains of domination. But again, the absence of a political theory that could articulate a free space for the development of subjectivity continued to be missing. This led it to projects such as federalism as an answer to the centralizing state, Carl Schmitt as a critique of liberalism, and Christopher Lasch and populism as a ground for the participatory subject. The hope was that a mash-up of these ideas could “reinscribe the earlier philosophical defense of subjectivity within an analysis of contemporary realities predicated not on the primacy of economic relations but of the culture and politics which determines [sic] the nature of these economic relations.” At the same time, Piccone was very clear that the only way to approach the current crisis was through a theoretical analysis from a totality that integrated particularity, subjectivity, and individuality, not “concrete political analysis.” The latter, he believed, was simply a deployment of predominant prejudices that led to conservatism and conformism. But as he also pointed out, when stuck in a present that appears to be directionless and unable to reinvent itself, the immanent possibilities that were initially set forth can provide radical possibilities for a ubiquitous present.

Telos depends on subscriptions in order to continue its work. You can help by subscribing or by downloading or ordering articles through your library. Your downloads and requests help to convince librarians to continue subscribing or to open a new subscription. Thank you for your support!

Really nice summary of an article/perspective that still manages to get my blood flowing.

But as David Gross correctly pointed out in 1994 “most people connected to the Journal are not immediately connected to the people.” Yet possibly an inversion of interest will become available in 2023 — where a sophisticated discussion of federal populism, I am willing to bet, might now find a much more receptive audience among the people (but certainly not among most academics)–why not test this out on Rumble, Substack and maybe even Twitter.

Its’ time for Telos rekindle some excitement and cash.

Jim. Thanks for the positive response. Glad you found it worth rereading. Re; your reference that “most people connected to the Journal are not immediately connected to the people,” I”m never quite sure what that is supposed to mean. I grew up in a working class family, and then spent 30 years in financial services interacting with what we called HNWI, high net worth individuals. Does that make me connected to the “people”? (By the way, I like your piece from wayback on the financial crisis.) How are the people defined? Most of Telos’ contributors and editors are in education; I think they’re connected to the people. Is it because we engage in critique rather than activism? Would we be more relevant if we took it to the streets? Yes, the point is not to understand the world, but to change it. But first you have to expose the irrational in what is not actual to engage in the change.

Hi Florindo, to my great sadness I feel that Telos somehow lost its mojo after Paul’s death and has never recovered. Piccone, for me, was an intellectual scrapper of the highest order who was in the academic community but never really a part of it. He didn’t appear to have the necessary diplomatic finesse to really make it in that environment (thank goodness).

I identified with what I would call his partial outlaw aura and in that sense viewed him as more linked to the average girl or guy]–I ended up running a term paper company in California for almost 40 years(all I had to fall back on were my research skills after my multiple political failures) and know all to well the most unseemly dimensions of academia— and consequently admired his skepticism about the place.

i also came from a working class background (neither of my parents made it beyond high school) and my going to graduate school was meet with extreme suspicion in my family–and they were correct–I initially saw graduate education as a ticket to the West coast and an escape from having to find a job plus a once in a life-time chance to enjoy the surf and turf (both sand and race tracks) of Southern California.

I also did the take it to the streets politics (for about 13 years and a complete failure in every effort from more traditional union organizing (SEIU) to attempts to persuade female clerical workers in downtown San Francisco to join a Lenninist/feminist political group that maintained that it was female clerical workers who did all the real work and were perfectly positioned to take over corporate management in some kind of coup–this was all before computers. This latter real life experience helped to make me into the heterodox decentralist populist that I am today!