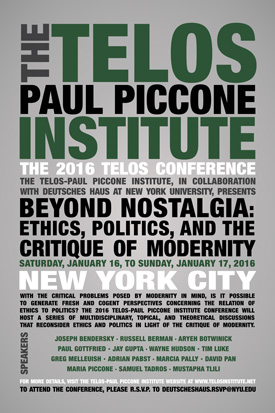

This short text was presented at the annual Telos Conference in January 2016, two months after the ISIS attacks in Paris. The March attacks in Brussels give the matter even greater poignancy.

Traveling in Paris, Judith Butler published a “letter” dated November 14, in English on the Verso blog and in French in Libération, the day after the ISIS attacks, entitled “Mourning becomes the Law.”[1] The short text treats two phenomena and argues for a connection between them: the process of mourning the victims of the attacks and the expansion of counter-terrorist practices by the state. Butler’s thesis is that the shared grieving of the dead served exclusively as a vehicle to justify amplified police powers: in this sense, mourning becomes the law, or at least law enforcement. A close look at her claims, however, shows significant deficiencies in the account of mourning and an important misreading of the Parisian response.

Traveling in Paris, Judith Butler published a “letter” dated November 14, in English on the Verso blog and in French in Libération, the day after the ISIS attacks, entitled “Mourning becomes the Law.”[1] The short text treats two phenomena and argues for a connection between them: the process of mourning the victims of the attacks and the expansion of counter-terrorist practices by the state. Butler’s thesis is that the shared grieving of the dead served exclusively as a vehicle to justify amplified police powers: in this sense, mourning becomes the law, or at least law enforcement. A close look at her claims, however, shows significant deficiencies in the account of mourning and an important misreading of the Parisian response.

Acts of mourning have several ethical dimensions: a fulfillment of an obligation to the deceased, to be sure; an obligation to oneself to engage in an act of healing in order to facilitate future participation in society; and especially, obligations to others, the community, in a process of consolation and reconstitution: in the wake of a loss, one shares in order to heal and rebuild. In contrast, Butler offers a solely instrumentalist account of mourning, as if public grieving in the aftermath of the attacks amounted to nothing more than propagandistic manipulation.

To be fair, she does take note of dispersed, individualized responses: “Everyone I know is safe, but many people I do not know are dead or traumatized or in mourning. It is shocking and terrible.” However, perhaps because she does not know any of the victims, or because she is a visitor in the city, she maintains an affective distance. For rather than dwelling on the experience of loss, she leaps immediately to a politicization, or rather: she accuses the public discussion of politicizing the event: “It seems clear from the immediate discussions after the events on public television that the ‘state of emergency’, however temporary, does set a tone for an enhanced security state. The questions debated on television include the militarization of the police (how to ‘complete’ the process), the space of liberty, and how to fight ‘Islam’—an amorphous entity.” Thus, for her the public response is only an instrument with which to establish a police state: mourning is merely the manipulation of affect for political ends: no tear is genuine. She then counters with a symmetrical politicization of her own, the implication that any discussion of Islam or Islamism in the wake of the attacks can only be Islamophobic. This leaves us with a dogmatically bifurcated discussion. Genuine mourning over the loss of life therefore disappears behind the too familiar terms of political debate: more or less security, or the choice between the managed terminology of a non-specified extremism and describing the terror as explicitly Islamist.

Butler’s interest clearly lies in insisting on the instrumentalization of grief: whatever might have been authentic in experiences of sadness turns immediately false when the state responds, as if the public and the individuals that make it up lack any agency of their own and a national mourning is necessarily propagandistic: “It was interesting to me that Hollande announced three days of mourning as he tightened security controls. . . . Are we grieving or are we submitting to increasingly militarized state power and suspended democracy? How does the latter work more easily when it is sold as the former?” The rhetorical questions should not be mistaken for hesitation; Butler has the stylistic habit of using soft and noncommittal phrasings to achieve hard insinuations. Her argument is clear. For Butler the state “sells” grief in order to suspend democracy in the form of the state of emergency. That there might be legitimate security concerns (are there any real terrorists?)—or genuine grief (can anyone be sad about the loss of life?)—is never considered. On the contrary, the French capacity to rally in response to the threat and to mobilize security capacities is treated with derision, as when she denounces the president: “Hollande tried to look manly when he declared this a war, but one was drawn to the imitative aspect of the performance so could not take the discourse seriously.” It is surely ironic that Butler, the theoretician of gender performance, chooses to attack Hollande for performing, and for performing masculinity no less. For this she calls the elected leader of the French people a “buffoon.” In other words, she regards his capacity to provide national leadership in the face of the attack as a clownish fraud.

Her target is however not primarily Hollande but rather the character of the French response altogether: France mourns wrongly, according to Butler. Where others might see a nation in grief, she sees buffoons, because the very prospect of national community represents a failing: “Mourning seems fully restricted within the national frame,” she writes, i.e., the shared national experience is necessarily deficient, presumably racist in its parochialism, as she immediately continues: “The nearly 50 dead in Beirut from the day before are barely mentioned, and neither are the 111 in Palestine killed in the last weeks alone, or the scores in Ankara.” The phrasing raises two issues, one concerning Butler’s cavalier treatment of facts, the other a matter of principle. Regarding the 111 in Palestine, she evidently drew on a newspaper article that had appeared days before hers about 111 shot and wounded in Palestine, but she chose to treat the wounded as killed, either out of sloppiness or as an editorial decision on her part to change the facts to better fit her narrative.[2] Be that as it may, what is of greater interest is the principled implication of her internationalist gesture: any national grief must be immediately relativized with reference to loss elsewhere, because any national mourning can be upbraided for failing to recognize the pain of others. The here and now must always be eclipsed by the then and there, in an infinite process of competitive victimization. She labels this process “transversal grief,” the obligation to subordinate losses that are close, spatially or metaphorically, to losses that are distant.

Yet she is herself susceptible to the same critique with which she denounces the French national frame: if the French fail to recognize losses in Ankara, one could counter that Butler has omitted from her list the stabbing victims in Israel or the hundreds executed in Iran or the longer list of dead one could easily compile from around the world. In effect, Butler’s internationalist critique of national mourning disallows any local mourning as inescapably too narrow and specific. In fact, the logic of her critique also implies that the only legitimate mourning must involve mourning all the dead, everyone who has died anywhere, but also everyone who will ever die too. More likely though, the implication of her choice of counter-cases—Beirut, Ankara, Palestine—is that some deaths are given higher status than others on political grounds; by doing so though she engages in the same, or rather a symmetrical preferential mourning of which she accuses the French. Just as she faults the French for ignoring Ankara, she ought to fault mourners in Pakistan for forgetting India, or mourners in Beirut for forgetting Columbine. There is something deeply repressive about this, since it forbids the recognition of the particularity of loss. If I lose a loved one, must I subordinate my grief to abstract principles and political correctness?

“Mourning Becomes the Law” exposes the deficiencies in certain aspects of Butler’s political thought as elaborated in other recent writings, especially the volume Parting Ways. I want to mention two points relevant to the larger discussion of ethics and politics.

First, Butler maintains a fundamental hostility toward any political community. The national community of grief in France is, for her, merely the propaganda machine for the police state, a dystopic vision symptomatic of the simplistic reductionism Butler borrows from Michel Foucault. Moreover her critique of this nationalization of mourning implies that she sees recognizes no distance between Hollande and Marine LePen, except that the latter may not be a masculinist buffoon. For Butler it appears that any talk of the French nation is always already the National Front. This indicates, to say the least, insufficient political nuance on her part. Yet this animosity toward national community is consistent with her attack on what she calls “solidaristic” community in Parting Ways. In that context, to be sure, she develops claims specifically about Jewishness and its (so she argues) diasporic imperative that should preclude community allegiances, but she suggests frequently enough that this same critique applies to all nation states or national communities. Any community allegiance short of universalism is, so she implies, necessarily racist. Conversely the relationship to the stranger is for her the genuine paradigm of ethics, not the obligation to the family, clan, or nation. With that turn, Critical Theory, which developed as a critique of alienation, strangeness, turns into its opposite, an elevation of estrangement over community.

Second, in the Paris letter, Butler expresses deep suspicion of the French state (not just the nation). While she is concerned with the development of police and security policies, she suggests that these outcomes are always potentials in the very nature of the state itself. This apprehension is consistent with her anarchist predisposition elsewhere to regard all state power as threatening. Thus, parallel to the critique of national community, she also rejects the state as an expression of sovereignty, especially (but not only) national sovereignty. Hence her argument in Parting Ways that a “rule of law,” understood as the application of the statutes of a sovereign state, is necessarily and always an oppressive expression of state power and therefore inimical to justice, which she locates instead in a “prelegal” quasi-divine space.

It is worth noting that, facing the development toward a security state in France, the anarchist Butler retreats to a civil libertarianism and a de facto appeal to the same beneficent rule of law, which she otherwise rejects. Aside from this inconsistency however, another issue emerges: Her internationalism, the globalizing insistence to discount any national grief as always flawed due to its exclusionary character, goes hand in hand with a denigration of positive law and any national legal system, hence her anarchism. (That outcome can be read as consistent with Carl Schmitt’s claim, e.g., in Land and Sea, that the regime of globalization or universalism tends to subvert local orders and thereby generates conditions of lawlessness.) Butler’s objection to the militarization of the French state, it follows, turns out to be an objection to any state, a stance which is symptomatic of a widespread post-political mood: on the right and on the left, massive suspicion of the state. This legitimacy crisis of the state as such, and the national communities of solidarity that once subtended it, is the corollary to globalization and deregulation and therefore the appropriate framework within which to treat ethics and politics today. Butler’s anti-statism is closer to neo-liberalism than her progressive followers are likely to admit.

Notes

1. Sarah Shin, “Mourning Becomes the Law; Judith Butler from Paris,” Verso blog, November 16, 2015, http://www.versobooks.com/blogs/2337-mourning-becomes-the-law-judith-butler-from-paris, accessed November 27, 2015. The Verso blog byline attributes the piece to Sarah Shin, but it is evidently a text by Butler. (The piece has since been removed but is archived here.) A French translation, attributed to Butler, appeared in Libération on November 19: “Une liberté attaqué par l’ennemi et restraint par l’état,” http://www.liberation.fr/france/2015/11/19/une-liberte-attaquee-par-l-ennemi-et-restreinte-par-l-etat_1414769, accessed November 27, 2015.

2. “Palestinians shot, injured during West Bank, Gaza demonstrations,” Ma’an News Agency, November 13, 2015, https://www.maannews.com/Content.aspx?id=768807, accessed November 27, 2015.