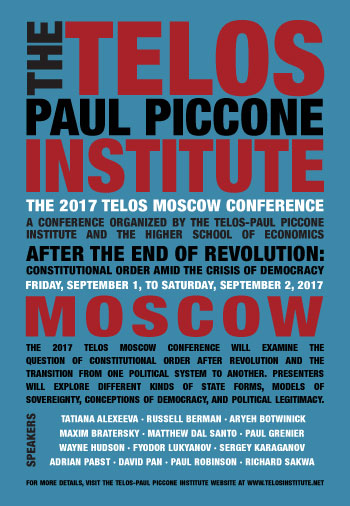

The following paper was presented at the conference “After the End of Revolution: Constitutional Order amid the Crisis of Democracy,” co-organized by the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute and the National Research University Higher School of Economics, September 1–2, 2017, Moscow. For additional details about the conference as well as other upcoming events, please visit the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute website.

The idea of liberal democracy only makes sense because of a basic contradiction between liberalism and democracy. As a description of a form of government, democracy designates a government by the people, whose decision-making power would not be restricted by any higher authority. The power of democracy derives from its ability to mobilize a majority of the members of a political order for collective goals. This rule by popular will can also entail a freedom from higher authorities, including such entities like monarchs and aristocrats, but also ecclesiastical or moral authorities that would establish basic values for guiding decision-making. Since democracy alone would lack constraints on the popular will, liberalism, as a set of principles that include protection of minorities and freedom of expression, is needed to provide the limitations on democratic decision-making that protect democracy from erratic and changes in the public mood. As such, liberalism sets a limit on democratic power, and the basic contradiction between democracy and liberalism maintains a dynamic equilibrium between popular will and liberal principles that can be stabilizing due to its flexibility.

The idea of liberal democracy only makes sense because of a basic contradiction between liberalism and democracy. As a description of a form of government, democracy designates a government by the people, whose decision-making power would not be restricted by any higher authority. The power of democracy derives from its ability to mobilize a majority of the members of a political order for collective goals. This rule by popular will can also entail a freedom from higher authorities, including such entities like monarchs and aristocrats, but also ecclesiastical or moral authorities that would establish basic values for guiding decision-making. Since democracy alone would lack constraints on the popular will, liberalism, as a set of principles that include protection of minorities and freedom of expression, is needed to provide the limitations on democratic decision-making that protect democracy from erratic and changes in the public mood. As such, liberalism sets a limit on democratic power, and the basic contradiction between democracy and liberalism maintains a dynamic equilibrium between popular will and liberal principles that can be stabilizing due to its flexibility.

The weakness lies in the way in which liberal limits might be discarded if appeals to democracy and popular will overcome the legitimacy of liberal institutions. The protection of liberal rights falls often to the authority of the courts, which can be undermined over time in a number of ways. In addition, the subordination of substantive values to a kind of liberal relativism threatens to weaken the political will behind liberal principles as opposed to the transcendent ones that dominate at the level of specific communities and cultures. At the same time, liberalism sometimes has a hard time recognizing the legitimacy of such cultures, especially when they contradict the individualist principles of liberal order and instead enforce community restrictions on individual freedom. Finally, the liberal notion of justice, though claiming a kind of objectivity and universality, is not organized as a democratic institution, and its traditions and institutions do not present an objective or logical extension of democratic principles. But neither do they represent a kind of neutral set of procedures without metaphysical presuppositions, as liberal theory often presumes. Liberal democracy may not be the universal, objective norm toward which the whole world is moving, but a very particular historical construct.

The particularity of liberalism opens up the idea of alternative forms of non-liberal democracy, in which the popular will is not limited by liberal principles but rather by alternative traditions such as religious or nationalist ones. Yet, such a non-liberal system would then have a basic difficulty in protecting minority rights. Does this difficulty undermine the very idea of a non-liberal democracy? How can we evaluate such alternative forms of democracy? Can they be considered democracies at all? How do we evaluate, for instance, an Islamic democracy such as Iran? Can it maintain an independent judiciary and therefore a consistent rule of law while also adhering to Islamic legal principles? These questions are particularly relevant for the United States today in its renewed effort at nation-building “lite” in Afghanistan. For if such an effort is to succeed, it will be important to understand the possibilities and limitations of the liberal democratic model that the U.S. has generally used as its model for nation building.

To address this issue, I would like to analyze the precise role of the rule of law and an independent judiciary in liberal democratic theory. While they are clearly the key to maintaining liberal protections in a democracy, liberal theory often assumes that legality forms the basis of sovereignty, meaning that the rule of law is grounded in itself and not in a framework of sovereignty that determines the character of law. This understanding would preclude substantive differences between different legal systems because they would all converge on the same universal principles, allowing for a kind of “legal cosmopolitanism,” in which a single legal system could span the world and ensure peace.

Hans Kelsen, an important defender of this conception in Germany during the Weimar Republic, sets up such an idea of law as an objective science against metaphysical conceptions in which law would be grounded in some form of divine law. In his system, the laws are justified by their relationship to norms that have been legislatively codified. These norms make up a hierarchical system in which each norm refers back to another norm as its justification. The form of justification is not a moral or even logical one, however, but a procedural one. Each norm gains legitimacy because it has been established using the procedures of the system of law as laid out in the constitution. Because each norm refers back to a previously established norm that lays out the procedure for new laws, the hierarchy of norms leads ultimately back to an original constitution and a ‘basic norm’ that guarantees the legitimacy of that constitution as the result of an act of political will.[1] Since the basic norm does not refer to some idea of justice but to an original act of will that establishes the constitution, human will replaces divine law as the guarantor of the legitimacy of laws,[2] and there are no natural or divine laws that would legitimate positive laws.

In this conception, Kelsen must confront the arbitrary character of human will as a basis of law. The difficulty that he accurately identifies and that defines the problematic of legal theory in the early twentieth century, however, is that the founding of law on an act of will rather on divine law makes the basis of law into a relative rather than an absolute value. He consequently claims that legal theory can remain unperturbed by the way a revolution can completely transform the basic norm and change the meaning of law.[3] He imagines a revolution that overthrows a monarchy and replaces it with a republican government. If the revolution succeeds, then it introduces a new set of laws that defines certain actions as illegal that were previously legal. But if the revolution eventually fails, then those same actions defined as illegal in the republican government would have to return to legality. He insists here that the law is indifferent to such a radical transformation in its meaning, indicating that law has no intrinsic direction or tendency for Kelsen, only a unified procedure. The same act can be interpreted as either the establishment of constitutional order or as high treason, depending on who is politically victorious. Instead of maintaining an absolute basis for justice, Kelsen allows for a political will to be completely defining for the structure of the legal system. Justice no longer has a consistent meaning and becomes a neutral tool of the legislator’s will, whatever this will may decide about the overarching norms according to which the law must function.[4]

Kelsen accordingly rejects a metaphysical understanding in order to recognize the irrationality of the idea of justice and its consequent uselessness as a basis for a theory of law.[5] As there is only positive law whose only justification is that it has been passed by the legislator, there is no concept of justice that would be distinguished from those positive laws. The question of the basis of laws in a concept of justice is for Kelsen irrelevant because any basis is just as valid or invalid as any other.

Because Kelsen abandons justice as something that is distinct from positive law, he suppresses any discussion of sovereignty as the embodiment of a metaphysical idea that would justify a particular conception of order and the laws emanating from it.[6] This suppression of the question of sovereignty forces him to equate law with the state. One consequence here is that he treats law rather than the state as the only basis of order. He presumes a fundamental separation between norm and reality, “ought” and “being,” which means that it takes a judge’s pronouncements to turn natural being into a judicial situation.[7] Kelsen’s judge begins deliberations by directing attention at an instance of “natural being,” and he presumes that this natural being does not have any kind of moral direction before the advent of the judge. But in imagining a parallel world of “natural being” that is disconnected from norms, Kelsen returns to the basic starting point of the theory of natural law—the state of nature. Like the original theorists of the state of nature, such as Grotius, Hobbes, and Locke, Kelsen imagines a natural state preceding law. The imagination of this “normless” state presupposes the possibility of a kind of action that is detached from any understanding of its ethical implications, and the spectre of such a lawless state becomes the justification for the rationality of both natural law and the purity of law. Kelsen’s reliance on positive law as the only law thus presumes that the absence of positive law is the same as no law at all. Consequently, he does not actually take seriously his own claim about the relativism of law because he does not accept the validity of a sovereignty that would precede law. Since the absence of law is a state of nature, only law can rule, and law thus replaces sovereignty.

Though he rejects natural law as itself a kind of metaphysical presumption that is external to the purity of law, his construction of the separation of “being” from “ought” reproduces the structure of natural law’s reasoning, and contemporary readings of Kelsen tend to make sense of his work by re-inserting a natural law framework for the legitimacy of the legal order he imagines.[8] The difficulty with this merging of law and sovereignty is that it leads to a single liberal conception of law and order, which establishes itself continually in opposition to other political and legal systems as well as to other cultures. Alternative foundations for sovereignty appear irrational or backward, not constituting any kind of system at all but a lack of order.

If the liberal view sees order as only possible through natural law or the Kelsenian equivalent of a legislative will, the alternative would be to imagine human action as always, by definition, linked to a context of meaning and of justice. Such a perspective would understand law, not as the point where ethical norms are imposed upon actions that would otherwise be completely amoral, but as itself arising out of an already existing sense of justice. As part of his polemic against Kelsen, Carl Schmitt insists that “ought” and “being” must be treated as inseparable from each other, and he criticizes the very idea of a norm for creating a separation that alienates law from society.[9] Because “ought” and “being” should exist for Schmitt in an intertwined relationship, he avoids speaking of law as something separate from natural being, but chooses the term nomos as a concept that maintains the unity of actions with ethical judgments. Schmitt links nomos to land appropriation, in which both Ordnung [order] and Ortung [orientation] are inseparable, and meaning and will exist in a unity. The establishment of nomos is both a physical and metaphysical process to the extent that the will cannot attain any efficacy without the link to a metaphysical meaning. Justice needs to remain part of the fabric of human will itself. Schmitt’s implicit critique of Kelsen is consequently that the pure theory of law makes all law into a set of commands from above as opposed to guidelines that already exist within human action.[10]

Schmitt’s framework assumes that all sovereignty includes order and, moreover, that only sovereignty can establish order to the extent that order without sovereignty is in fact an ideal order rather than a really existing one. Sovereignty therefore is not the opposite of law nor the same as law, but its prerequisite. Critiques of this Schmittian conception of order typically treat his insistence on the primacy of state sovereignty for human order as a kind of fetishization of violence.[11] But in arguing that Schmitt sees sacrifice and violence as goals in themselves, this critique does not recognize the way in which a metaphysics already suffuses every existing state order of sovereignty. The argument for sovereignty is not that sacrifice is a goal in itself, but that order cannot maintain itself in the world except as a specific structure of sacrifice that creates the restrictions on activity that make up a human order. Schmitt’s notion of sovereignty makes sense, not because the link between order and sacrifice is a desideratum, but rather because human order can only by definition consist of some structure of self-constraint, which is itself a sacrifice, a self-imposition of limitations on one’s behavior in recognition of an order that goes beyond the self. A “headless” order such as the one presupposed by natural law lacks the notion of sacrifice that would establish a structure of self-restraint. Instead, natural law is explicitly based on the generalization of a principle of self-preservation and thus of a kind of self-interest that ignores the constitutional necessity of a human subjection to something greater than the self.

If order is a result of the sovereignty of a metaphysical conception rather than of law, then we may need to understand liberalism not so much as a universal legal order but as a system that mediates between competing metaphysical conceptions. While this can happen within a liberal democracy through the protection of individual rights, this can also happen in international relations through a general attempt to defend minority rights while accepting a variety of systems of sovereignty. But recognizing competing foundations for sovereignty, each one able to establish a separate basis for legality in its own sphere, does not mean placing no limits on sovereignty. Rather, a key task for liberalism would be to continue to maintain different competing levels of sovereignty that would lead to ways of mediating relationships between states as well as between states and their internal minorities.

Notes

1. Kelsen, Reine Rechtslehre: Einleitung in die rechtswissenschaftliche Problematik (Leipzig: Franz Deuticke, 1934), p. 64.

2. Ibid., pp. 65–66.

3. Ibid., pp. 67–68.

4. Carl Schmitt makes this point by indicating that the legal system that Kelsen lays out is ultimately based on a command from above. Carl Schmitt, Politische Theologie: Vier Kapitel zur Lehre von der Souveränität (Munich and Leipzig: Duncker und Humblot, 1934), p. 30.

5. Kelsen, Reine Rechtslehre (1934), pp. 15–16.

6. Hans Kelsen, Das Problem der Souveränität und die Theorie des Völkerrechts: Beitrag zu einer reinen Rechtslehre (Tübingen: Mohr, 1920), p. 320. On this point, see Carl Schmitt, Politische Theologie: Vier Kapitel zur Lehre von der Souveränität (Munich and Leipzig: Duncker und Humblot, 1934), p. 31.

7. Kelsen, Reine Rechtslehre (1934), pp. 6–7.

8. David Dyzenhaus, “Positivism and the Pesky Sovereign,” The European Journal of International Law 22.2 (2011): 363–72; here, p. 367.

9. Carl Schmitt, Der Nomos der Erde im Völkerrecht des Jus Publicum Europeaeum (Berlin: Dunker & Humblot, 2011 [1950]), p. 38.

10. Ibid.

11. David Dyzenhaus, Legality and Legitimacy: Carl Schmitt, Hans Kelsen, and Hermann Heller in Weimar (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999), pp. 94–97. Lars Vinx, Hans Kelsen’s Pure Theory of Law: Legality and Legitimacy (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2007), p. 204.