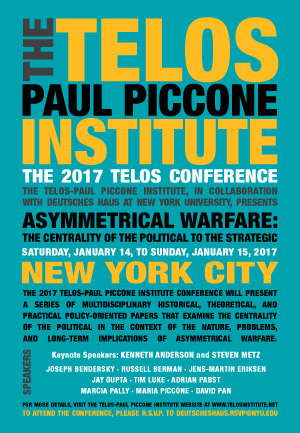

An earlier version of the following paper was presented at the 2017 Telos Conference, held on January 14–15, 2017, in New York City. For additional details about the conference as well as other upcoming events, please visit the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute website.

This paper focuses on the modern practice of using law, both national and international, to achieve policy goals and political ends that usually are the result of tactical military action. Lawfare, as this practice is referred to, is now a crucial tactic in the modern era of international relations, where war is largely carried out in a far from traditional manner. Lawfare, then, is a unique form of irregular warfare that can be employed by nations against one another and against insurgents in asymmetrical conflicts at home and abroad. This new reliance on irregular and asymmetrical warfare generally and lawfare specifically is reflective of Hegel’s view of the end of history, particularly as articulated by Alexandre Kojève. Basically, that as individuals gain equal recognition, the mode of satisfying desire will necessarily take the form of law and bureaucracy.

This paper focuses on the modern practice of using law, both national and international, to achieve policy goals and political ends that usually are the result of tactical military action. Lawfare, as this practice is referred to, is now a crucial tactic in the modern era of international relations, where war is largely carried out in a far from traditional manner. Lawfare, then, is a unique form of irregular warfare that can be employed by nations against one another and against insurgents in asymmetrical conflicts at home and abroad. This new reliance on irregular and asymmetrical warfare generally and lawfare specifically is reflective of Hegel’s view of the end of history, particularly as articulated by Alexandre Kojève. Basically, that as individuals gain equal recognition, the mode of satisfying desire will necessarily take the form of law and bureaucracy.

Individuals and NGOs Waging Lawfare through Tort

In the case of individuals’ and NGOs’ use of lawfare, lawfare allows such parties to act offensively against states and paramilitary or terrorist organizations that they would be overwhelming disadvantaged if not powerless against in traditional kinetic warfare. Lawfare in these cases is asymmetrical warfare being waged by parties that traditionally are kept to the sidelines of geopolitical conflict. Additionally, these actions can be significant strategically not only because they can result in financial hardships stemming from frozen assets and crippled sources of funding for the targeted party, but also because the discovery process may result in the uncovering of intelligence that is found to be actionable by state parties.

Orde Kittrie, in his recent Lawfare: Law as a Weapon of War, an excellent survey and analysis of lawfare in its many forms, cites several such instances of tort lawfare employed by non-state actors that have occurred in the war on terror. Most of these cases involve the plaintiffs relying on the 1990 Anti-Terrorism Act (hereinafter the ATA) to win judgments against those that sponsor terrorist acts. In pertinent part, the ATA reads: “Any national of the United States injured in his or her person, property, or business by reason of an act of international terrorism, or his or her estate, survivors, or heirs, may sue therefor in any appropriate district court of the United States and shall recover threefold the damages he sustains and the cost of the suit, including attorney’s fees.”[1] It should be noted that at the time of Kittrie’s writing, the ATA had a far wider reach and degree of efficacy than the Alien Tort Statute, the reach of which was significantly curtailed in 2013’s Supreme Court decision in Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Company (held that the ATS does not provide jurisdiction in U.S. federal courts for actions occurring overseas).[2]

The reach of the ATA, however, appears to have been drawn back as well by the 2nd Circuit’s ruling in Sokolow v Palestine Liberation Organization. The decision vacated the decision finding the PLO and the Palestinian Authority liable to U.S. victims and their survivors of terrorist attacks occurring between 2001 and 2004 in the Israeli–Palestinian region. The lawsuit, brought under the ATA, resulted in an award of $655.5 million. The 2nd Circuit however, vacated this ruling, finding insufficient ties between the PLO and the Palestinian Authority to establish personal jurisdiction to bring suit in the United States. This ruling may be a significant setback for the practice of lawfare through tort, especially by United States citizens seeking damages from parties such as the Palestinian Authority for acts committed outside of the United States and who have few financial or fundraising activities inside this country. What remains to be seen, however, is how lawsuits originating under 2016’s Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act, the so called 9/11 Bill, which provides for suits against foreign nations but only for attacks occurring in the United States, will be prosecuted, damages collected, and what effect such litigation will have on diplomatic relations between the United States and foreign nations named as defendants.

Relation to the End of History

This reliance on legalistic, even bureaucratic, methods to achieve ends that were until recently primarily the domain of traditional, kinetic warfare, could indicate that we are coming closer to, if not having already arrived at, Kojève’s (via Hegel) end of history, the establishment of the “universal homogenous state.” This end of history, first mentioned in the thinker’s Introduction To the Reading of Hegel is not the conclusion of history or the lack of recordable events; it is more along the lines of the end of competition between contradictory societal models. As Francis Fukuyama, in his own writing on the subject, cited here in his initial National Interest article, wrote of Kojève’s universal homogenous state, “all prior contradictions are resolved and all human needs are satisfied. There is no struggle or conflict over ‘large’ issues, and consequently no need for generals or statesmen; what remains is primarily economic activity.”[3]

This growing use of lawfare as a primary tactic is indicative of the realization of two aspects of what Kojève saw as the “universal homogenous state” that was to come at the end of history: universal recognition of all men and the establishment of universal system of order—in our case, an order based on finance and regulated by law. Essentially, as law and finance are used to order relations between states, and even within a state, historical action ceases and is replaced with an absolute and universal regulatory regime. Defiance on the part of international actors is not even historical action but rather criminal or tortious action. Think here of rogue states and terroristic tortfeasors.

For Kojève, the end of history built on Hegel’s notion of the same, starting with the basic idea that history was a process having both a start and a finish. Hegel famously saw history ending in 1806 with Napoleon Bonaparte’s victory over the Prussian monarchy, and Kojève was, for the most part, in agreement. History ending does not mean that there will no longer be events but rather that human society has completed its evolution through conflict that result in the establishment of a universal homogenous state in which individuals are recognized as free, autonomous, individuals. Kojève was well aware that there was indeed conflict after the end of history, but saw it as part of the process of finalizing the aforementioned universal state.

Kojève saw the achievement of absolute recognition of all people as autonomous individuals, thus negating the need for continued conflict for such recognition between masters and slaves, as signaling the end of history. This not to say there would not be conflict, but rather that conflict would be between parties that are legitimate autonomous beings worthy of recognition as opposed to inferior beings to be subjugated, dominated, and made to submit to a master will. The recognition granted by legal standing for individuals that makes lawfare possible and attractive can be seen as this very absolute and universal recognition. This recognition is essential for the use of lawfare as a tactic, be it used by an individual seeking recourse against a state, international corporate entity, political organization (including ones deemed to be terroristic and thus illegal) or vice versa. Human desire (including that pursued by states and other legal entities) may now be satisfied geopolitically by the granting of a legal remedy where in the past only political violence or other historical action would have been a logical recourse. Without the recognition of standing juridical geopolitical strategy would be pointless and actors would have to continue to rely on traditional kinetic warfare strategies.

One could argue that finance’s current supremacy over all traditional political concerns, such as sovereignty, is what makes lawfare an attractive and useful weapon and even sets the stage for its deployment. At this stage in history, where it appears that human desire is best satisfied in wholly economic terms, it seems only logical that wrongs on the global scale would be seen to be righted best in terms of monetary damages. This observation leads to what may be the greatest drawback to the growing pervasiveness of lawfare usage: that despite its ability to strategically cripple enemies without the traditional risk of additional casualties, it imposes an imperfect justice and, as it becomes more and more relied upon by victims of terrorism or other hostile act, runs the risk of imposing the imperfect justice of tort law universally. Even if one discounts the difficulties collecting judgments resulting from successful lawfare (and the difficulties are not really discountable), one must still face the dilemma that judgments stemming from legal action will not often be satisfying on the moral and visceral levels for citizens of sovereign states that find themselves or loved ones harmed by global actors.

Notes

1. The Anti-Terrorism Act, quoted in O. F. Kittrie, Lawfare: Law as a Weapon of War (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 2016), p. 53.

2. Kittrie, Lawfare: Law as a Weapon of War, p. 54.

3. Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History?” National Interest, Summer 1989.