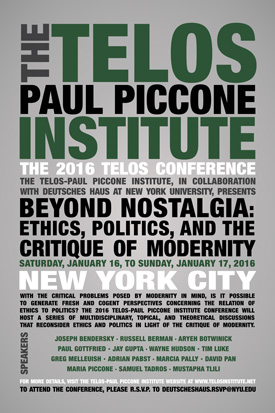

An expanded version of the following paper was presented at the 2016 Telos Conference, held on January 16–17, 2016, in New York City. For additional details about this and upcoming conferences, please visit the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute website.

In today’s public life, marked by large-scale migration, welfare states under pressure, and a soaring right-wing scene, “multiculturalism” and “right-wing populism” remain at the center of political debate. It is assumed, moreover, that they stand in sharp opposition to one another. On the one hand, multiculturalism is widely acclaimed for being progressive, radical, and safely leftist. It is seen as a vital precondition for a modern society: tolerant, humble, and anti-racist. Anyone who opposes multiculturalism, then, will be deemed at best a conservative or reactionary—if not outright racist, xenophobe, nationalist, or fascist. On the other hand, we have right-wing populism. Due to its allegiance with racism, virulent nationalism, and fascism, right-wing populism has a dubious reputation. Multiculturalism, as it seems, is anything that right-wing populism is not.

In today’s public life, marked by large-scale migration, welfare states under pressure, and a soaring right-wing scene, “multiculturalism” and “right-wing populism” remain at the center of political debate. It is assumed, moreover, that they stand in sharp opposition to one another. On the one hand, multiculturalism is widely acclaimed for being progressive, radical, and safely leftist. It is seen as a vital precondition for a modern society: tolerant, humble, and anti-racist. Anyone who opposes multiculturalism, then, will be deemed at best a conservative or reactionary—if not outright racist, xenophobe, nationalist, or fascist. On the other hand, we have right-wing populism. Due to its allegiance with racism, virulent nationalism, and fascism, right-wing populism has a dubious reputation. Multiculturalism, as it seems, is anything that right-wing populism is not.

This popular image of right-wing populism as the negation of multiculturalism is not entirely unfounded. Right-wing populists oppose immigration, while multiculturalists endorse immigration. While the former have warm feelings toward their own culture, the latter are at best indifferent. In media, in academia, and in politics, no relation is more tense and hostile than the one between a right-wing populist and a multiculturalist. One way or another, any contemporary political debate contains the assumed conflict between multiculturalism and right-wing populism.

Still, I shall below argue that, this commonsensical antagonism between the two does not hold water. Under the veneer of superficial antagonism, similarities abound. Eight of these similarities will be addressed. I shall do so by tracing their common roots back to the Counter-Enlightenment of the early nineteenth century and the philosophy of the German relativist and romantic Johann Herder.

First, Johann Herder considers the idea of “belonging” as crucial, whether the allegiance is to an ethnic group, a culture, a race, or a religion. Right-wing populism is unthinkable without the idea of belonging to something great and majestic. From the other corner of the room, multiculturalists talk passionately about the fusion of “I” and “we.” Early multicultural theorists such as Lawrence Blum and W. E. B. Du Bois were influenced by Herder’s ideas of a “collective spirit” of an ethnic group.

Second, Herder claims that foreign cultures devour expressions of indigenous culture “like a cancer.” What do right-wing populists and multiculturalists say about this? Right-wing populists, to start with, see intrusion and colonization in anything foreign. The unknown is the poison, and the cure and rescue are constituted by the familiar. It is a paramount virtue, says the multiculturalist, to save fragile culture overseas from “detrimental” Western influence. In this respect populists and multiculturalists are both pessimistic and express sentimental and self-pitying emotions regarding “their” culture. The fact that right-wing populists are sentimental on behalf of their own culture while multiculturalists are emotional regarding cultures overseas makes little difference.

Third, Herder sees the nation as an organism with acting limbs—the population—and a thinking head—the enlightened representatives. The multiculturalists make use of a similar image: the “ethnic spokesperson” and “community leader” who gives voice to his downtrodden community. Similarly, the organic idea was always part-and-parcel among right-wing populists. They do the thinking and they give voice to the downtrodden, silent, and humiliated person on the street. Again, similarities between multiculturalism and right-wing populism emerge.

Fourth, Herder’s philosophy is infused by rebellious pessimism: “Awake, German nation! Do not let them ravish your palladium!” Germans must be on guard. What about the right-wing populists? Similar rhetoric. “Deutschland erwache!” cried Hitler—and right-wing populists merely express milder versions of the same battle cry. The multiculturalists? They are as myopic and bellicose only on behalf of cultures overseas.

Fifth, Herder is often a primitivist and anti-intellectualist. He cherishes the simple man and “his wife and his child”—a man who “works for the good of his tribe.” Multicultural primitivism and hatred toward modernity is no different—only on behalf of foreign lands. The “Other” is simple and introverted and offers a constant temptation to those westerners who cannot tolerate the achievements of modernity. The right-wing populists, then, express exactly the same anti-intellectual idealization, but the objects of their admiration are the indigenous simple people, abandoned by the socialists, and abused by the “media elites and the artists.” The primitivist anti-elitism among multiculturalists and right-wing populists is very similar.

Sixth, language, Herder says, is the key to national identity. Germans, speak German, he exclaims: “Spew out the Seine’s ugly slime.” At this point, the multiculturalist and the right-wing populist are mirror images of one another. While the multiculturalist goes out of his way to protect the language of ethnic minorities, at the same time as the language of the host country is belittled, the right-wing populists sinks his heart into his native tongue, while dismissing the language of ethnic minorities.

Seven. As a relativist, Herder does not recognize opinions and values about Germany from abroad. Any opinion worthy of consideration must be made from within the borders of any one culture. Always prone to self-mysticism, right-wing populists cannot accept “foreign” views about their own culture, because these supposedly universal opinions are inherently abstract, arrogant and meaningless. The ideology of multiculturalism rests on the idea that “the West” does not have any right to “interfere” and “impose our values” on cultures overseas. Universalism is but another name for imperialism. In a similar fashion, they all dismiss the optimistic and modernist ambitions of universal values and individual autonomy. They all exercise relativism. It is all about culture.

Eight. One of the values that went missing during the Enlightenment of the late eighteenth century, its critics maintained, was the notion of roots; of background, of history and seamless connection with the voices of the past. The British conservative Edmund Burke was one of these critics. Johann Herder was another. Without the notion of roots, multiculturalism is unthinkable. The virtues of background, history, and identity on the part of exotic cultures all offer a battery of arguments against the supposedly detrimental impact of western “rootlessness.” In reverse colors, the right-wing populist says the same thing. The notion of roots is vital in any right-wing populist rhetoric—against the disintegrating influence of globalization and “waves of immigration.”

Whether we talk about the idea of belonging, about the impact of foreign cultures, about the nation as an organic metaphor, about national awakening, about language, relativism, or roots, a number of salient similarities emerge between multiculturalism and right-wing populism. They are merely two branches of one crooked, romantic tree.

Göran Adamson is Associate Professor of Sociology at West University, Sweden.

Edmund Burke was not British but Irish. Don’t drag him into your anti-liberal diatribe of disguised right-wingery.

This is a distressingly simple minded piece of fluff. As a thinker, Herder deserves better. As a magazine of serious repute, so do you. I am seriously considering terminating my Telos subscription as more and more of your issues contain neo-liberal rants like these.

Dear Mr Beers and Mc Cormack,

Thanks for your comments! Would you care to read the article referred to above? The empirical findings are mainly based on previous research by Isaiah Berlin. And the idea of common roots of multiculturalism and right-wing populism goes back to George Orwell´s Notes on Nationalism.

With best regards,

Göran Adamson