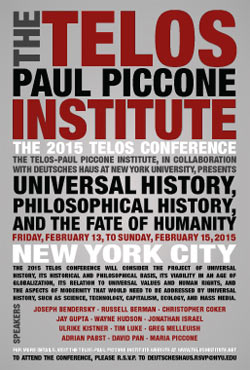

The following paper was presented at the 2015 Telos Conference, held on February 13–15, 2015, in New York City. For additional details about the conference, please visit the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute website.

The worldwide reaction to the Charlie Hebdo attacks can be seen as a welcome indication of a global consensus concerning freedom of speech, individual rights, and opposition to Islamic fundamentalism. However, left-wing critics such as Noam Chomsky have criticized the worldwide demonstrations against the attacks as hypocritical because they ignore the more serious massacres that have been conducted by Americans with drone strikes and in military activities in Iraq, Serbia, and Syria. As Chomsky writes, “[a]lso ignored in the ‘war against terrorism’ is the most extreme terrorist campaign of modern times—Barack Obama’s global assassination campaign targeting people suspected of perhaps intending to harm us some day, and any unfortunates who happen to be nearby. Other unfortunates are also not lacking, such as the 50 civilians reportedly killed in a U.S.-led bombing raid in Syria in December, which was barely reported.” Such an equation of “their terror” with “our terror” is based on an image of a universal history in which all of mankind lives within a unified natural community and there is a single standard of measure that could be the basis of criminal behavior. We see this same approach in a more moderate form in Jack Miles’s similar exhortation that the proper response to ISIS and Al Qaeda is that “[y]ou are criminals and we send criminals to jail” rather than declaring a “war on radical Islam.” For both Chomsky and Miles, terrorist attacks count as criminal activity and should be equally condemned from the universal viewpoint of a peace-loving humanity. By diminishing the difference between criminal violence and war, they illustrate the basic tenet of a version of universal history—that all humans are linked together into a common set of natural laws and that such laws transcend historical and political differences. Every war in this perspective would be just as senseless and unjustified as any other form of murder. Teju Cole and Slavoj Žižek make a similar move when they indicate that there is something hypocritical about the support for Charlie Hebdo when other massacres, such as the one by Boko Haram in Baga, Nigeria, go unnoticed and unmourned.

The worldwide reaction to the Charlie Hebdo attacks can be seen as a welcome indication of a global consensus concerning freedom of speech, individual rights, and opposition to Islamic fundamentalism. However, left-wing critics such as Noam Chomsky have criticized the worldwide demonstrations against the attacks as hypocritical because they ignore the more serious massacres that have been conducted by Americans with drone strikes and in military activities in Iraq, Serbia, and Syria. As Chomsky writes, “[a]lso ignored in the ‘war against terrorism’ is the most extreme terrorist campaign of modern times—Barack Obama’s global assassination campaign targeting people suspected of perhaps intending to harm us some day, and any unfortunates who happen to be nearby. Other unfortunates are also not lacking, such as the 50 civilians reportedly killed in a U.S.-led bombing raid in Syria in December, which was barely reported.” Such an equation of “their terror” with “our terror” is based on an image of a universal history in which all of mankind lives within a unified natural community and there is a single standard of measure that could be the basis of criminal behavior. We see this same approach in a more moderate form in Jack Miles’s similar exhortation that the proper response to ISIS and Al Qaeda is that “[y]ou are criminals and we send criminals to jail” rather than declaring a “war on radical Islam.” For both Chomsky and Miles, terrorist attacks count as criminal activity and should be equally condemned from the universal viewpoint of a peace-loving humanity. By diminishing the difference between criminal violence and war, they illustrate the basic tenet of a version of universal history—that all humans are linked together into a common set of natural laws and that such laws transcend historical and political differences. Every war in this perspective would be just as senseless and unjustified as any other form of murder. Teju Cole and Slavoj Žižek make a similar move when they indicate that there is something hypocritical about the support for Charlie Hebdo when other massacres, such as the one by Boko Haram in Baga, Nigeria, go unnoticed and unmourned.

This equating of all murder regardless of context ignores the element of ideology that is the key element of both the attack on Charlie Hebdo and the worldwide response. Neither was hypocritical. Both were ideological and principled, and that is what makes both into part of an unfolding war rather than criminal activity. There is in fact a connection between the Charlie Hebdo attacks and the continuing French military actions against radical Islam in both Africa and in the Middle East, illustrating the political divides that undermine the claims that all murder is equal and that terrorism should be treated as criminal activity rather than war. If Chomsky and Miles feel that their stance is based on a justified universal notion of humanity, then the contrasting insistence on the distinction between war and murder is based on a pluralist conception of humanity in which political differences are differences in principle, that is, differences in conceptions of what is right and wrong. For the attackers, trained in Yemen, Charlie Hebdo’s depiction of Mohammed and its cartoon attacks against Islamist fundamentalism were deeply immoral forms of blasphemy and cause for a violent response. If they had been alone in their beliefs, then one could plausibly treat their actions as isolated criminal activity. But not only were they trained by other Islamist fundamentalists based in Yemen, their actions found support in scattered demonstrations in places such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, and Russia. On the other hand, the global show of support for the victims of the attacks were clearly not motivated simply by the fact that French lives might be somehow more valuable than Nigerian lives. As the attack was directed against a set of representations, the support for the victims was motivated by a support for the principles they represented—freedom of speech, individual rights, and a tolerance for religious differences. While it is tempting to frame these values as those of a universal humanity, it would be in fact a disservice to those values to characterize them in this way. If they were truly universal in the same way that, say, the incest taboo can be said to be universal, there would be no need to emphatically defend them. It is precisely the particular character of these values that makes their defense such a priority and in fact a matter of war when necessary.

Here, the French response has been exemplary. There has been a clear attempt to distinguish between Islam and the violent Islamofascism that motivated the attacks. The French laws on freedom of speech distinguish carefully between defamation of a religion or an ethnic group in general, which is banned, and the critique of particular ideological positions, which is allowed. This is the distinction that has protected Charlie Hebdo’s cartooning in the past from censure by the courts and has by contrast led to convictions for Brigitte Bardot, for example, for engaging in hate speech against Islam. That this distinction has been lost on disaffected Muslim youth in the French suburbs is clearly a problem, but one that the French have been moving to ameliorate through an increase in civic education in schools and a reaffirmation of their commitment to freedom of speech and the secular status of the state. Crucially, there has been a strong attempt to avoid a demonization of Islam itself, and the emphasis on the concept of laïcité plays an important role in opposing the right-wing attempt by Marine Le Pen and the National Front to portray Islam itself as incompatible with French identity. The particular importance of laïcité is, however, not as a form of universalism that bridges between different faiths. Instead, we must understand laïcité as the particular French mode by which the nation establishes its political primacy above all religions, which are confined to the private sphere. This French nation is not defined by religious or ethnic identity but by a commitment to a common history grounded in the French Revolution and its Declaration of the Rights of Man. While there is an obviously universalist, natural law interpretation of these rights, the intertwinement of these rights with the history of French national identity in fact reinforces the connection of these rights with the political will and thus the particular historical trajectory of the French people. They can therefore defend individual rights as the most essential part of their historical legacy while also maintaining their consciousness that such rights need to be continuously defended and justified within a contemporary context.

Here, the French have indicated in recent opinion polls that they are even more committed than before to their military interventions in the Middle East and Africa against radical Islamic militants (Montvalon). The drawing of the link between the Charlie Hebdo attacks and the broader conflict with ISIS and Al Qaeda is justified by the particular character of the ahistorical vision of universalism that we find in Islamofascism. As Russell Berman has pointed out, we need to understand today’s militant Islam not so much as a purely Islamic movement but as an Islamofascism that is descended from twentieth-century European totalitarian movements such Nazism and Stalinism.[2] If this is the case, then the particular danger of Islamofascism is the way in which, like Nazism and Stalinism, its vision of universalism is part of an expansionist movement that is not limited to a state or a state structure, but which seeks to establish itself as a constantly expanding vision of the universal that would overrun more and more regions of the world and that would violently punish transgressions against its own rules for the public sphere in all countries of the world.[3] Like the racist universalism of the Nazis or the mix of Slavic and communist universalism of Stalinism, in Islamofascism, or perhaps more accurately Islamo-totalitarianism, the emphasis is on undermining the state system through the expansion of its own vision of a universal system of values. The global show of solidarity with France, then, was not merely a case of mourning for the particular victims of the attacks, but of a clear support for freedom of speech as well as a rejection of the kind of universal notion of the public sphere that would ignore state boundaries and laws that would govern the public sphere as a territorially bounded space.

If the rules of a public sphere ultimately derive from a particular interpretation of the history of the place in which it applies and therefore of a specific collective’s political will, the scope of application of this political will must also be spatially limited in order to avoid the kind of unfettered extremity of violence that we are seeing with Al Qaeda and ISIS. Such a self-limitation of the ambitions of a political will, even if it is a will toward individual rights, does not imply a relativist stance in which rights abuses in other countries are to be ignored. In the first place, the defense of individual rights as a particular politically willed set of habits must set itself forcefully against the challenge of universalist ideologies such as Islamo-totalitarianism that would attempt to curtail those rights all over the world. In this sense, one of the best ways of helping the Nigerians against Boko Haram is precisely the global show of solidarity with French ideals that could then form the ideological basis for a more focused military intervention in Nigeria. In the second place, the defense of individual rights must understand these rights first as the outgrowth of particular histories of development of the public sphere in a set of countries and second as a potential trajectory for other countries that can only arise through historical struggles that would shape the habits of the public spheres of those countries. Outsiders can certainly influence historical developments by providing support for those elements in a country that can establish a tradition of individual rights. Such support could run the gamut from conquest and long-term occupation, as was the case with the Allied occupation of Germany after World War II, to a kind of outside encouragement of the defense of human rights as happens to a certain extent in the current relationship between the U.S. and China. In these different cases, the key to productive intervention is the consciousness and encouragement of those aspects of a culture that already tend toward the promotion of freedom of speech and individual rights. But in the end the real struggle and decision-making that would establish enduring change must go on within the local public sphere seen as an independent and separate historical development. If there is a universal history here, it would be only perceivable as a kind of bird’s eye view of a contingent interaction of different separate public spheres with each other, perhaps akin to the development of a biosphere as the result of the separate struggles and developments of the individual species within its bounds.

The unit of agency of these developments must remain, however, the state as the fundamental unit of human freedom. As the territory that is governed by a uniform set of laws, the state will set the bounds of a particular public sphere and the set of values by which that public sphere will be organized. As the basic unit of sovereignty, the state is also the particular bounded sphere in which a political will must establish its hegemony and its vision of guiding principles that form the basis for its laws as well as its foreign policy. For it will not be a single set of immutable, universal laws that will determine the course of a world history, but the separate judgments that different sovereign states will make about their engagement with, opposition to, and intervention in the interests of competing states.

Notes

1. I would like to express my gratitude to Ève Morisi for her invaluable advice and encouragement in preparing this essay.

2. Russell Berman, Freedom or Terror: Europe Faces Jihad (Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 2010).

3. Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1973).