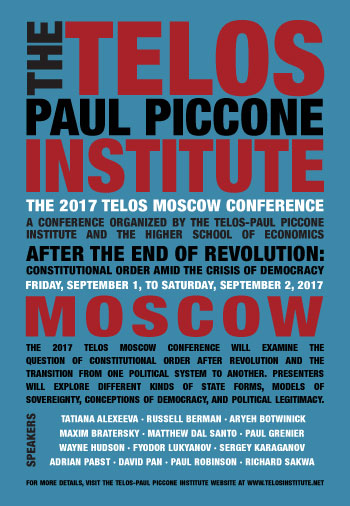

The following paper was presented at the conference “After the End of Revolution: Constitutional Order amid the Crisis of Democracy,” co-organized by the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute and the National Research University Higher School of Economics, September 1–2, 2017, Moscow. For additional details about the conference as well as other upcoming events, please visit the Telos-Paul Piccone Institute website.

It is important not only to analyze the legacy of the Russian Revolution of 1917 from the point of view of historical science, but also to bear in mind its impact on the modern information and ideological processes. Discussing the Russian Revolution has become a way to think and talk about today, and different approaches to the discussion correspond to different views on modernity and different political ethics.

It is important not only to analyze the legacy of the Russian Revolution of 1917 from the point of view of historical science, but also to bear in mind its impact on the modern information and ideological processes. Discussing the Russian Revolution has become a way to think and talk about today, and different approaches to the discussion correspond to different views on modernity and different political ethics.

There are five approaches to the evaluation of the Russian Revolution in the ideological space of today: the classic liberal, the neoliberal, the Western left, the Russian left, and the traditionalist approach.

I

The first approach evolved in the years of the Cold War and still maintains an important place in contemporary Western sources. It may be called classic liberal approach. It is based on the values of the market economy, democracy, and civil liberties. It is founded on the belief that the February Revolution had done Russia good, while the October Revolution was the absolute evil.

This approach declares that the February Revolution had been long brewing in the Russian society and thus was inevitable. It was founded on European values, which gave the people of Russia the hope for democratic reforms according to Western models.

The October Revolution receives the opposite evaluation, and is described here as the Russian doom, which had brought about the end of democratic beginnings and the beginning of terror and totalitarianism. The liberal approach designates the October Revolution as “anti-European” one and claims that it had closed the window to Europe.

This approach was practicable throughout the Cold War and served the purpose of confrontation with the socialist block. Today, it remains a base structure out of inertia and supports the de-Sovietization policy for several countries of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Pro-European governments also tend to adapt it to suit their needs by omitting the topic of February in the public narrative completely, and focusing on October, the Bolsheviks, and their crimes instead. Stemming from the logic of war, this approach pursues the necessity of the “Tribunal” for post-October Soviet history and its condemnation at the international level.

II

The collapse of the USSR and the establishing of liberalism in Russia made the February/October confrontation irrelevant and put an end to the search of possible historical scenarios that would have served to avoid disaster and to redirect the 1917 energy into a peaceful channel. Deprived of this contradiction, the classic liberal approach lost popularity.

Where this liberal approach was tied to specific historical themes and was based on the February–October dichotomy, the neoliberal approach appears to be completely divorced from historic events as it consists of exalting the idea of revolution as the engine of history and development. The February events are of no interest, and the October Revolution is historically and morally separated from all the subsequent Bolshevik actions. Willing to divorce the idea of revolution from the historic Soviet reality, neoliberalism is prepared to go even further. The Bolshevik theory of social democracy is separated from its practical application in Russia. It is only characterized negatively to the extent in which it was “distorted” by the Russian reality, Bolshevism, and the figures of Lenin and Stalin. The social-democratic ideas are viewed positively as taking their origins from European philosophical thought and supporting democratic freedoms.

It is quite possible that in the future, when the ideas of Bolshevism and the figure of Lenin are separated from their associations with the Soviet history and with Russia, they will become a legal part of the neoliberal ideology, whose doctrine is founded on the idea of the necessity of revolutions, crises, and conflicts.

III

The classical liberal approach to the theme of revolution was traditionally opposed in the West by the left view of the revolution.

The approach of Western left to the 1917 events was formed in the twentieth century simultaneously with the right, or classic liberal approach. The word “Western” in this case is a definition of values, not a geographic area. It is based on three propositions: (1) that the February events in Russia should be considered only in the context of October, and not as a separate revolution; (2) that the October Revolution is a historic achievement and a blessing; and (3) that starting with Stalin, the Bolshevik rule in Russia had little in common with the socialist ideals. The classic left-minded defended the idea of socialist revolution and thus differed from classic Western liberals.

The so-called “new left” continue to be inspired by the idea of revolution—only in a broader sense. They seek to overthrow the hierarchy of global capital and to take revenge over a large period of history starting with the era of geographical discoveries. The new left do not have much interest in the events of 1917, and they see no contradiction between the February and October, and little enough between Lenin and Stalin.

The essence of their approach is a definitely positive attitude to the phenomenon of revolution (in this case, the anti-capitalist kind). Therefore, ideologically, both the old and the new left adhere to the neoliberal approach.

IV

Modern Russian left and socialists (in contrast to the Western left) hold the memory of the Soviet socialist project and the great October socialist revolution in great esteem. Unlike the Western left, they tend to give positive evaluation not only to the Lenin era but also to the whole Soviet period up to the end of the Soviet Union. Russian socialists base their beliefs not only on the idea of social justice but also on historical memory.

When Lenin monuments are publicly demolished in different countries as political demonstrations, various political, religious, and social Russian strata often perceive these as acts of Russophobia, though their attitude to Lenin may vary from love to hate. The left idea in Russia is related to the specific historical experience and, consciously or not, is regarded as part of Russian identity.

V

Along with the given approaches to the events of 1917 and the phenomenon of revolution, there exists today another point of view, which is called the traditionalist approach. It cannot be called conservative, as it does not seek to “conserve” a particular historic period. Rather, it is metahistoric and appeals to the Christian worldview. In modern Russia, this approach is found both in the intellectual sphere and in the public consciousness. It is based on the idea that revolutions bring only evil and are enforced by an evil will, no matter how beautiful its slogans are. There are no ends that justify revolutionary means. This idea is deeply rooted in the Russian consciousness and has become especially clear after the events of perestroika and the collapse of the USSR, and in view of the ongoing era of instability that both Russia and the world are now experiencing. Even the term “revolution” became associated in the Russian language with neoliberal ideology and the politics of Western interventionism.

This approach was especially strengthened in Russian society and in Russian official political language in the early 2010s, amid background attempts to implement a color revolution in Russia and the beginning of the Ukrainian crisis.

The traditionalist view of the 1917 revolution and the phenomenon of revolution in general is also gradually developing in modern Western philosophical thought. This approach equally rejects the bourgeois, socialist, or color revolutions. It is mostly shared by those think tanks and philosophers whose views are close to traditional Christianity, and who oppose the situation with secular values dominating the modern world.

* * *

Therefore, from the point of view of political ethics, the diversity of approaches to the Russian Revolution is reduced to the neo-liberal and the traditionalist ones.

The neoliberal approach is the direction that the classic liberal approach and the Western left are moving toward. The neoliberal approach pays less attention to February, gives more attention to October, justifies the October events, and considers the phenomenon of revolution to be a positive and important mechanism of historical progress and development of society. Here the theory of revolution is separated from its tragic practices.

The traditionalist approach becomes strengthened as a response to international instability and the rise of local conflicts, often flared with the help of revolutionary mechanisms. This approach is based on the thesis that revolutionary methods are vicious by nature.

Vasiliy A. Shchipkov, PhD in Philosophy, is a Lecturer at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO), Director of Russian Expert School.