Once upon a time, there was an illusion that the state would disappear. It was the fiction Marxists told each other at bedtime, and it was the lie of the Communists, once they had seized state power. For even as they built up their police apparatus and their archipelago of gulags, they kept promising that one day the state would eventually disappear.

Once upon a time, there was an illusion that the state would disappear. It was the fiction Marxists told each other at bedtime, and it was the lie of the Communists, once they had seized state power. For even as they built up their police apparatus and their archipelago of gulags, they kept promising that one day the state would eventually disappear.

Of course, in a sense, they were right because Communism ended and so did the Communist states in Russia and Eastern Europe. Yet the death of those regimes is in no way an argument for the death of statehood itself.

The state is the expression of sovereignty, and sovereignty is the ability of national communities to decide their own fates. Such independence is far from obsolete, and certainly not for the countries on the eastern flank of the European Union. After years of Russian occupation, they have regained their state sovereignty. They will continue to insist on it, and rightly so.

Capitalists, too, have indulged in the fantasy of the end of the state, especially in the neoliberal version of an economy free of political constraints. This peculiar fiction grew pronounced in the millenarian hallucination of an “end of history,” which preached that the epochal change of 1989 had ushered in a Kantian era of perpetual peace. Global capitalism was supposed to erase borders, replacing national solidarities with abstract universalism.

Genuine conflicts were predicted to dissolve into rules-based competition, while existential threats would dissipate in a thoroughly benign cosmos. After all, with the fall of Communism, all enemies had disappeared, which made states obsolete.

Hence the idealists’ horror at the rise of national populisms after the 2008 financial crisis. Today respectable public opinion still views populism as deplorable, hoping that the next election cycle will bring a return to a normal trajectory of an ever-diminished nation-state, ever-larger supranational organizations, and a programmatic neutralization of all political decisions.

A Pandemic Upsets the Old Order

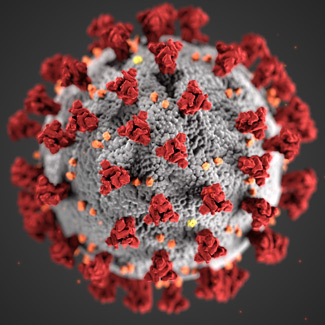

And then came the virus from Wuhan, the global pandemic that signals the end of globalization and therefore the reassertion of the state, for several distinct reasons.

First, despite the illusions—Marxist, capitalist, or anarchist—that the state will vanish because the world is a friendly place, the virus reminds us that danger never disappears. The state is the vehicle with which a political community can respond to ever-present existential threats. One prominent feature of the response to the pandemic is the recognition that sooner or, sometimes tragically, later the state must respond to enemies. The responsibility to do so rests ineluctably with the political leaders who must make crucial decisions. Without them and without the state, we would be helpless. (The mirage that the state might end is nothing more than an expression of what Karl Heinz Bohrer once called “der Wille zur Ohnmacht.”)

When Donald Trump banned travel from China in January, his critics called him a racist. When he stopped travel from Europe, those same critics complained that he acted too slowly, while the EU leadership denounced him for acting alone. Within a week, the European Union instituted travel bans similar to those for which they had attacked Trump, but only after leaders of individual states, such as Austria’s Sebastian Kurz, had made similar decisions.

It is no coincidence that we have seen national leadership emerge by way of renewed assertions of control over national borders: a state that cannot control its borders is a failed state. The border closings of 2020 are the retraction of the German border openings of 2015.

Second, the reemergence of the state marks the end of globalization in a pending economic restructuring. The excessively praised free flow of capital opened national economies to foreign direct investment, just as it enabled companies that developed in one country to shift production and investment overseas, in search of lower wages. Yet all that glittered was not gold. Chinese capital buying up European firms has damaged domestic economies and contributed to accelerated technology transfer, legal and illegal: recall the Kuka case.

In response, Western countries have begun to subject foreign investments to national security scrutiny because it might not be wise to sell off one’s domestic industries to foreign investors beholden to undemocratic and hostile regimes.

Today, however, similar national security concerns are being raised with regard to the globalization of supply chains. For the United States most medicine, including even penicillin, is manufactured in China: we can thank the starry-eyed globalists for this dangerous vulnerability. Fortunately, there are now moves afoot to bring supply chains back home, while also retrieving jobs thoughtlessly exported overseas. Deglobalization is the watchword of the state.

Coming to Terms with China

Third, the willingness to sacrifice state sovereignty in the name of globalization was always based on a misunderstanding about China. The West has fooled itself repeatedly that Communist China would undergo a political liberalization. It never did.

China remains a dictatorship ruled by a Marxist-Leninist party. During the past half-century of the supposed rapprochement with China, it has neither liberalized, nor established an independent judiciary, nor carried out free and multiparty elections. Sadly, China’s access to Western economies was never made contingent on any respect for human rights.

While Western states subordinated themselves to the illusions of post-nationalism—the European Union is the best example—China only grew stronger as an illiberal surveillance state. Hence the crisis of the Wuhan virus: Chinese authorities knew of the illness in December, if not earlier, but they chose to suppress the information, punishing the brave whistleblower professionals who tried to sound the alarm. If addressed promptly, the novel coronavirus might have been contained in Hubei province.

Instead, thanks to the Chinese leadership and its lies, we face a pandemic, with countless deaths and enormous economic losses. Party Chairman Xi Jinping should be held accountable for this suffering. There are no grounds ever again to believe any statistic coming out of China—at least not until Beijing allows the Chinese people to enjoy freedom of speech and a free press.

The China question, however, is not only about the origin of the virus or even the vicissitudes of globalization. This coronavirus moment reminds us that the genuine purpose of the state is to respond to all dangers that jeopardize the life of the political community. The family of Western democracies—not only in the geographic West but also on the periphery of the Eurasian landmass, including South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, India, and Israel—face concerted efforts by China and Russia to disrupt the world order. To be sure, Chinese and Russian interests do not always coincide, and they engage in complicated relations with North Korea and Iran, hardly satellites in the Cold War sense, but ultimately all are part of a multifaceted challenge to our ways of life.

It is not because the virus came from China that we should recognize these dangers, but the virus is an acute reminder that the world is replete with threats, whether epidemic or political, military or economic. Those who argue for the end of the state have to explain who else, other than the state, will ward off another invasion, such as took place in Crimea, or prevent similar aggression in the South China Sea. The answer is: no one. The argument against the state is an argument for capitulation and powerlessness.

Such powerlessness is evidently attractive. It reflects a certain element of conflict-aversion inherent in human nature, especially endemic in the academic class. Yet our capacity to live in institutions of our own making—whether individual or collective—based on our traditions and our aspirations, is predicated on the will to mount a defense against external threats. The primary vehicle for self-preservation of the political community is the state. State sovereignty is the best chance we have to fend off adversaries. We defend our freedom by exercising power through the state, not through global illusions or cozy provincialism. This commitment to the state is called patriotism.

Russell A. Berman, Editor Emeritus of Telos, is the Walter A. Haas Professor in the Humanities at Stanford University and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution. This essay previously appeared in German in Neue Zürcher Zeitung and in English at American Greatness.