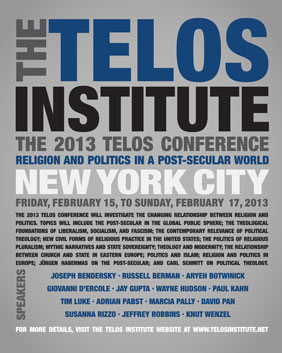

The following paper was presented at the Seventh Annual Telos Conference, held on February 15–17, 2013, in New York City.

In Faith of The Faithless: Experiments in Political Theology, Simon Critchley writes: “What is lacking is a theory and practice of the general will understood as the supreme fiction of final belief that would take place in the act by which a people becomes a people or by which a free association is formed” (92). Critchley’s work turns to poetics or “making” as a mode of engagement and resistance for dealing with democratic-liberal crises. I suggest that psychedelic aesthetics and religion can provide a discursive ground for Critchley’s “supreme fiction” in the United States, because the making of the sacrificial figure in the psychedelic experience presents itself as capable of more ethically aware citizenship. A brief historical look at religions founded in the 1960s gives insight into the instantiation of a certain citizenship.

In Faith of The Faithless: Experiments in Political Theology, Simon Critchley writes: “What is lacking is a theory and practice of the general will understood as the supreme fiction of final belief that would take place in the act by which a people becomes a people or by which a free association is formed” (92). Critchley’s work turns to poetics or “making” as a mode of engagement and resistance for dealing with democratic-liberal crises. I suggest that psychedelic aesthetics and religion can provide a discursive ground for Critchley’s “supreme fiction” in the United States, because the making of the sacrificial figure in the psychedelic experience presents itself as capable of more ethically aware citizenship. A brief historical look at religions founded in the 1960s gives insight into the instantiation of a certain citizenship.

In classic representations of the psychedelic experience, citizenship is “re-enchanted” through a broadened commitment transcending the authority of nation-states. A critique of modern subjectivity is performed as an allegory through ego-death and rebirth—metempsychosis or reincarnation. One’s body becomes the site of sacrifice through ingesting a psychedelic “sacrament,” disseminating ego into the material world while a perception “behind” subject-object relationships emerges. Such experiences prompted groups to start their own religions in the 1960s.

It is too easy to write this trend off as either vacuous New Ageism or sinister cultism, and I am not presenting the period as a panacea.[1] Emerging legislation made psychedelic substances illegal during the 1960s. While the Vietnam War’s legitimacy was debated, many citizens saw participation in the psychedelic movement and illegal drug use as a way to assert moral authority and self-determination over the nation-state (an empty but almost ubiquitous rite of passage for young Americans today). By the time LSD was made illegal in 1966, proponents of psychedelics had turned to the rhetoric of religion in order to claim psychedelics as entheogens. Such rhetoric often employed the aesthetic language of the occult and secret societies as obfuscation. As Timothy Leary’s legal trouble intensified, he adopted more and more of a quasi-guru status, claiming he was a “Hindu” when caught with possession of a joint of Marijuana that landed him a thirty-year prison sentence. We are right to question his sincerity.

In contrast to Leary, Art Kleps, founder of the Neo-American Church, was no fan of occultism. Initially promoting Leary as prophet of the church, Kleps excommunicated Leary in 1973 for his excessive “horse shit.” In his account of the Millbrook estate in the late sixties, where Leary and others of the League of Spiritual Discovery researched psychedelics and spirituality, Kleps writes: “I found nothing in my visionary experience to encourage me to believe in any occultist or supernaturalist system. . . . Instead, dualism of every variety was blown out the window, never to return” (Milbrook 8). Kleps started his own religion of “Boohoos” in 1965, attempting—by analogy to the Native American Church’s use of peyote—to claim the legal right to use psychedelic substances as religious sacrament. As Martin A. Lee and Bruce Shlain summarize, “Not surprisingly, the Boohoos lost their case in court when the judge ruled that an organization with ‘Row, Row, Row your Boat’ as its theme song was not enough to qualify as a church” (105).

Kleps’s church is truly the product of a kind of Yankee dim-witted accutezza, Kleps spoofs, but he spoofs with seriousness. He put together the puzzling Boo Hoo Bible: The Neo-American Church Catechism during the years following Millbrook’s collapse. The catechism is a mixed-media performance of identification and participation, requiring its reader to transcend the personal in an act that simultaneously simulates and dissimulates, establishing and overcoming the ironic. Integrating pulpy comics, news clippings, senate testimonies, and political-religious diatribes, the text presents a cosmology of simultaneity, which Kleps considers essential to psychedelic experience. A radical solipsism emerges that sees all conscious and unconscious life as part of one dream where meaning-making becomes completely associative.

Yet despite his solipsism, Kleps longs for transformation of citizenship, for a “new” American. At first this seems like standard antinomian individualism—a longstanding American tradition. Critical of Leary’s “translation” of The Tibetan Book of the Dead into the manual The Psychedelic Experience,[2] Kleps broke away from early models of psychedelic therapy that employ a guide and forty hours of prior, one-on-one psychoanalytic therapy and often for therapist to trip with patient. This model had been encouraged by Aldous Huxley and Humphry Osmond as a way to democratize mystical experience in order to create engaged citizens.[3] Leary’s view of democracy, much less controlled, called for a collective change in consciousness of all citizens. By the early seventies, both Leary and Kleps encouraged novice users to trip alone from differing rationales.

Individuals are to determine their own spiritual progress for Kleps. When he actually sounds serious in The Boo Hoo Bible, he says (riffing on Martin Luther) that “Acid is not easier than traditional methods, it’s just faster, and sneakier. If there is shit in the way, it has to be disposed of, and the veritable explosion of shit is, in many ways, an even more disagreeable experience than a constant dribble over a period of years” (19). Instant enlightenment is a shit-storm. One can reasonably expect that a large group of people’s mind-manifestations will be messy (think of the late 1960s). Enlightenment overcomes individuation.

Yet Kleps also presents a goal for tripping that is social in nature. The church will eventually offer accreditation sources for psychedelic therapists.[4] To do this he must invoke criteria for measuring a kind of liberal elitism. In measuring those criteria, a global civic quality arises:

To attempt to separate our cause from that of the millions starved, robbed, corrupted and killed abroad by the industrial military robot masters of the U.S. is nothing but cowardice and hypocrisy. Their suffering may buy our leisure, but never our freedom. Our religion grows here because it is needed, not because it is welcome. . . . You cannot expand your consciousness without joining the great task of expanding the consciousness of mankind. I do not propose this as a moral rule, but as a physical law. Anyone who supposes his spiritual “motion” can be measured relative to a static world, or to the motion of others, as if this were some sort of million mile dash, has missed the point of the psychedelic experience. (21)

The psychedelic experience, then, in its inability to be separated from human plights around the world, is not a nihilistic unveiling of our solipsistic nature, but an act of citizenship that transcends the authority of the nation-state. While successful trips are to be measured on a personal level, he simultaneously maintains the Vedic phrase repeated in Huxley’s writing, tat tvam asi or “thou art that,” ending one article for The Psychedelic Review stating, “the object is to become what you are” (124). As potentially empty as this may sound, Kleps cannot be summed up as naïvely unaware of one-dimensionality. He charges his readers to fight “phony attempts to make psychedelia look like just one more swindle that can be blended into all the other swindles and controlled by the super-swindlers in Washington” by dropping “our own forms, our own language and our own standards, as every genuine religious novelty has done in the past” (24). Kleps invokes “genuine religious novelty” as a method of resistance.

Spoofing with language is part of the method. Kleps’s statements is congruent with Giorgio Agamben’s call that “Law is . . . constitutively linked to the curse, and only a politics that has broken this original connection with the curse will be able one day to make possible another use of speech and of the law” (66). From Kleps’s spoofy Boo Hoo Bible to the famous testimonies of the Chicago Seven, to attempts to levitate the Pentagon and exorcisms of Senator McCarthy’s grave, psychedelic aesthetics perform the collapse of oath and law in an effort to redefine citizenship through enchanted speech, with extra-ordinary qualities as Agamben calls for, beyond the definition of human as the rational speaking animal. The courtroom antics do not merely rebel against authority; they rebel against the mode of language as law in a state of emergence. We see in psychedelic literature and art a collapse of image and text and attempts at visual and auditory representations of boundary-less states.

We can see intentional implementation of these aesthetics in Kleps’s own Senate testimony from 1966. Senator Burdick asks, “Mr. Kleps, would you mind telling me if you are really called Chief Boo Hoo?”:

Mr. Kleps: I am afraid so. It is difficult to explain this. That is always the first question that comes up. The reason we do it is to distinguish between the church and the religion. We think it is very important not to take ourselves too seriously in terms of social structure, in terms of organizational life. We tend to view organizational life as sort of a game that people play.

Later in the testimony, after threatening that making LSD illegal will prompt civil war, Kleps claims that LSD “puts you in the mind of God, and . . . God is not a verbal being as we are to such a large extent.” Kleps argues that current scientific and legal views of psychedelics are atheistic and “fundamentally erroneous.” Consciousness for Kleps is not sequential or an aggregation. Rather, consciousness works, as in a psychedelic state, by analogy, and feels experientially more anagogical. Speech and gesture collapse. In questioning the boundaries of modern subjectivity, psychedelic works opened up a way of thinking about what personhood is and what citizenship is, particularly in their attempt at re-orienting of the subject’s moral center. The shit-storm opens the possibility for gestural poetics beyond speech.

Kleps attempts to disestablish governmental authority by a return to “genuine religion” of double entendre through a collapse of sacred and profane. This cannot be written off as empty spiritualism. Rather, we should look here to “free association” of Critchley’s “faithless” congregation. The 1960s nostalgia for a return to the pre-political, to nature, and to early religion is certainly the product of modernity’s long-standing narrative of alienation from the state of nature, but psychedelic works situate that nostalgia through a journey to the timeless, mythological expanded ego and a return to the temporal or historical. In studying the psychedelic, we re-introduce time into the shitstorm of consciousness expansion. If the faithless are the liberal left, according to Critchley, political theology needs more thorough evaluations of the “spiritual” and the “religious.”

Notes

1. There is a more current exigency here. With the current re-introduction of psychedelic therapy into end-of-life care, there are implications here for discussions of “citizenship” as bios and the boundaries of “bare life” (zoe). We would do well to see tensions in the analogy between state-recognized religion as the qualified life of citizenship and re-enchanted attempts to found New Religion or “spirituality” as emergent zoe. Psychedelic aesthetics thus offers a discursive sphere for both bare and qualified life.

2. “It’s great stuff for the social control of ignorant peasantry, and that’s about it. A first-class horror show to terrify the kiddies into mindless obedience” (Millbrook 12).

3. While many readers may be familiar with Huxley’s Brave New World, in which the drug “soma” is used by the World State as an opiate for the masses, Huxley’s own view of the potential for mind-altering substances changed over his life, so much so that in his last novel, Island (1962), moksha—Sanskrit for “liberation” becomes the name of the state-sponsored drug.

4. First, however, “One of our most important objectives should be to drive the crack-pot faddists and the simple-minded occultists out of the temple and replace them with intelligent, literate, professional psychologists who know the meaning and use of the psychedelic experience” (20).

Works Cited

Agamben, Giorgio. The Sacrament of Language: An Archaeology of the Oath. Trans. Adam Kotsko. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2011.

Critchley, Simon. Faith of the Faithless: Experiments in Political Theology. New York: Verso, 2012.

Kleps, Art. The Boo Hoo Bible: The Neo-American Church Catechism. San Cristobal: Toad Books, 1971.

———. Millbrook: A Narrative of the Early Years of American Psychedelianism. Austin: OKNeoAC, 1975.

Lee, Martin A. and Bruce Shlain. Acid Dreams: The Complete Social history of LSD: The CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond. New York: Grove, 1985.